Real American Boy: How Our Byzantine Immigration System and Failed Economy May Have Made a Terrorist

It's likely Tamerlan Tsarnaev was just another angry young man in our brave new America, a burgeoning dystopia where mass murder suddenly seems like a weekly occurrence.

“I want you to think, Santosh. Washington is not Bombay. … Will the Americans smoke with you? Will they sit and talk with you in the evenings? Will they hold you by the hand and walk with you beside the ocean?”

V.S. Naipaul, “In a Free State”

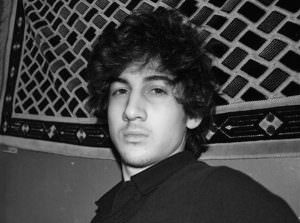

The story of Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev even sounds like a boxing movie. The older brother a heavyweight fighter, talented but a shade too cocky. The volatile eldest son of struggling immigrants, he feels every defeat, each small, shaming moment that adds up to a father’s lost life. The younger son? That’s easy. He worships his older brother. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev needed a role model, a winner in a society that gives no quarter to losers.

So goes the storyline of a New York Times article about the two young men accused of the Boston Marathon bombings that killed three people and injured nearly 300. According to the Times, the plot turned in 2010. Tamerlan Tsarnaev had won the New England Golden Gloves championship for a second consecutive year. He was poised to compete for the national title, but that year, the Golden Gloves changed its rules to bar fighters who weren’t citizens.

So here’s the plot twist: Tamerlan Tsarnaev had waited for a full year after he was eligible before applying for citizenship. One can hardly blame him. Immigration requirements are a hassle, even if you’re a patient sort. By the time he got around to submitting his application, there were two red flags: an FBI investigation that reportedly yielded no evidence of terrorist ties, and an incident allegedly involving domestic abuse.

At 26, Tsarnaev’s boxing career was over. To borrow from a real boxing movie, he could have been a contender. Instead, a series of events closed that door, and, according to family, friends and acquaintances, turned him toward radical Islam.

As debate over immigration reform played out in Washington, D.C., opponents brandished minor security glitches in the elder Tsarnaev brother’s record as a pretext for delaying S. 477, an 867-page bill that would thoroughly modernize the country’s immigration system. But if immigration debate in the U.S. wasn’t steeped in fear and identity politics, Tsarnaev’s story would have offered compelling arguments for passing reform — now.

Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s reaction to the difficulties his family encountered is his own, and no more a reflection of immigrants to the U.S. than mass killings by young American males wielding automatic weapons are of people born here. But the story of Tamerlan Tsarnaev and his family reveals the situation faced by many immigrants to the U.S., a country offering less solace than it once did to the world’s huddled masses, let alone its own citizens.

If you’re a software engineer from Bangalore, the ride may be relatively smooth, and if Mark Zuckerberg’s well-funded immigration reform group FWD.us succeeds, it will get even smoother. For others, the promised land turns out to be hell. That might sound like a familiar story too: the Cuban doctor waiting tables in Miami, the professor driving a cab. Or Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s father, Anzor, who went from being an official in the prosecutor’s office in Kyrgyzstan to working as an unlicensed mechanic in the back lot of a rug store in Cambridge, Mass.

What’s changed is the United States itself. Immigrants are struggling with the same problems as native-born Americans: stagnant wages, rising prices, unemployment or underemployment, and a health care system in perpetual crisis. In other words, they’re just like us, only without the long-standing ties to friends and family that many Americans have relied on as the economy spiraled downward.

That’s the real story behind the immigration reform fight that’s been playing out against the backdrop of deafening explosions, followed by parachutes of smoke and the shocked screams of the crowd.

It’s a truism verging on cliché: America has a schizophrenic attitude toward immigration. Send us your huddled masses, we say. But from the days when George Washington and Thomas Jefferson preached the virtues of isolationism, we have also been the country that executed Sacco and Vanzetti, turned away a boatload of Jews fleeing Hitler, and, more recently, tossed undocumented asylum seekers into solitary confinement. Our image of an immigrant is as Janus-faced as our attitude toward immigration itself: Horatio Alger with an accent or a welfare cheat. Now, a terrorist.

What isn’t as well known is how these attitudes shape our current immigration policy. The U.S. has the highest rate of immigration in the world, yet its system is both Byzantine and outdated, exacerbating the difficulties of integration for the 1 million people who migrate to the United States every year.

“The U.S. spends very little on immigrant assimilation,” said Michael Jones-Correa, a government professor at Cornell University. “Once immigrants are in the country they’re kind of on their own. The assumption is that once they’re in, they’ll make their own way and eventually become citizens. It’s a very laissez-faire approach.”

That laissez-faire approach is deeply embedded in America’s culture, according to Gary Weaver, a professor at American University and founder of its Intercultural Management Institute. Rooted in the 17th-century Calvinism of the British migrants who landed at Plymouth Rock, the U.S. ethos of self-sufficiency is a rarity among world cultures. Yet it flourished in what Weaver calls “the greenhouse environment” of 20th century America with its abundance of natural resources, limited population and a continually expanding economy.Welcome to the 21st century. While Americans fought about whether mojado Mexicans should be allowed to trim their hedges, Canada and Western European countries designed civic integration policies to deal with immigrant unemployment, school dropout rates and residential segregation. England did all that and more, requiring immigrants to learn “British mores and day-to-day life,” a list that included paying bills, standing in line and how to behave in pubs.

The immigration reform bill now before Congress doesn’t require answering test questions on Budweiser and the NFL, but it does include provisions that would substantially modernize the U.S. system. Many of the reforms are small scale, and even if the bill passed in its current form, the immigration process would remain difficult to parse without a law degree. But the bipartisan legislation, which incorporates virtually every aspect of contemporary thinking on immigration, lays the groundwork for moving U.S. immigration policy into the 21st century.

It is hardly a surprise that Republican support for the bill is based on changes that would benefit business. These include a new, merit-based program that would allow foreigners, including highly skilled white-collar as well as blue-collar workers, to become legal residents based on their talents. Other stipulations ease the way for graduate students and entrepreneurs, and establish a new visa category for agricultural workers. The bill would also lift restrictions on “Einstein visas,” which have prevented researchers and professors from attending conferences and working in the U.S.

But Jones-Correa and others fear proposals that aren’t tied to corporate and business profits could end up as trading stock for congressional deal makers. These include $10 million to create an Office of Citizenship and New Americans, and the establishment of a task force and foundation dedicated to immigrant integration. (The bill authorizes $100 million over five years for integration efforts, but since it’s unlikely that Congress will actually allocate that amount, the foundation could take up some of the slack.)

In the U.S., these kinds of social programs are often seen as frills, but immigration scholars consider integration an essential part of any country’s immigration policy. Funding immigrant integration is not only humane but in the national self-interest, according to Will Kymlicka, a professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada. In “Rethinking National Identity in the Age of Migration,” a book published by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, Kymlicka warned that “without proactive policies to promote mutual understanding and respect, and to make immigrants feel comfortable within mainstream institutions … [we could] quickly create a racialized underclass standing in permanent opposition to the larger society.”

As Kymlicka suggests, the real trouble is economic, but not in the way one might expect. The stereotypes are wrong: Studies have shown that immigrants don’t take jobs away from native-born Americans, and crime rates do not rise in immigrant neighborhoods. The problem, according to Jones-Correa, is that the most recent immigration boom, which added 47 million to the U.S. population between 1960 and 2000, coincided with the decline in American manufacturing. Without high-wage blue-collar jobs that historically led to upward mobility for both African-Americans and immigrants, the U.S. now lags behind other industrialized nations in social mobility.

Yet immigrants keep coming. American anti-immigrant sentiment is, in part, a reaction to rapid, sweeping changes in society, especially among older people, Jones-Correa says. On a day-to-day basis, one of the more visible signs is the presence of large numbers of immigrants. Unlike previous waves, the majority of recent immigrants are not Western European, but Latino and Asian. To compound the cultural disconnect, they are flooding into places that have little or no history of immigration. For example, in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Arkansas, Nevada, Tennessee and Nebraska, immigrant populations increased by at least 200 percent between 1990 and 2000.

Raw numbers are only part of the story. Harvard historian Samuel Huntington’s 1993 article in Foreign Affairs, “The Clash of Civilizations?” was controversial because it warned that the white Protestant culture no longer was the dominant influence in American society. Huntington’s apparent assumption of cultural superiority infuriated his critics, and his work was taken up by nativists. But his underlying idea that culture and religion were becoming the drivers in a post-Cold War world, was not quite so controversial. At least one thing is clear: As both capital and people stream across borders at an unprecedented rate, America’s immigration system, with its codification of Calvinist bootstrap self-sufficiency, simply isn’t working for a new generation of immigrants. It’s debatable whether this mindset is working for native-born Americans either.

In the admittedly extreme case of Tamerlan Tsarnaev, consider Chechnya. Chechen culture encourages male bravado, something that has helped Chechens keep their identity through generations of oppression in Russia, but that can make some Chechen men particularly prone to feelings of alienation. Oliver Bullough, an author who spent years researching the Chechen diaspora, told Reuters that Chechens who reached the West after the wars of the 1990s have had problems integrating, and these problems appear to be particularly acute for men who arrived as young adults.

As I combed through the articles and TV segments on the Boston bombings, Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s words kept coming back to me. “I don’t have a single American friend,” he confided to a reporter who was profiling the aspiring boxer for a student magazine. “I don’t understand them.”In the introduction to “Rethinking National Identity in the Age of Migration,” Demetrios Papademetriou, the founder of the Washington, D.C.-based Migration Policy Institute, and Ulrich Kober, a former Jesuit priest influential in Germany’s immigrant integration efforts, struck a surprisingly emotional note, emphasizing the importance of “an intangible factor in all this: the feeling of belonging.”

Jones-Correa, who has written several books on Latino immigration to the U.S. and served on the committee that redesigned the U.S. naturalization test for the National Academy of Sciences, says this critical element has been left out of the U.S. discussion of immigration. Countries with successful immigration policies, such as the Netherlands, Canada and Britain, speed immigrants toward full participation, not only with language lessons and civics classes, but also voting rights. The U.S. used to do the same thing.

“Historically, for much of the 19th century, up until 1921, in the majority of states you filed for what were called ‘first papers,’ ” Jones-Correa said. “Those stated that you intended to become a citizen, and in 24 states, that meant you could vote in state and federal elections. The expectation was that you learned how to become a citizen by participating.”

As anti-immigrant feeling took hold in the 1880s, states gradually stopped noncitizen voting. “Now citizenship is seen as a privilege,” Jones-Correa said. “It’s the culmination of a process. We don’t think of participation as something you want to encourage early on. We think of participation as something you do when you’re shown to be worthy.”

Disclosure may be in order here. As a reporter, I covered the enormous increase in immigration to the U.S. in the early 2000s. I wrote about the deaths of men and women on grueling treks across the Arizona desert. I listened to cattle ranchers on the U.S.-Mexico border describing fears that escalated as a biblical tide of economic refugees swept over the land. Riding along with the U.S. Border Patrol, I saw the inadequacy of militarizing the U.S.-Mexico border, or any border, as a response to millions of people whose lives had been devastated by globalization.

Like most Americans, I thought very little about “legal” immigration. My grandparents were Jewish immigrants who fled pogroms, and I’d always been grateful to the United States. I considered myself patriotic, not in a jingoistic way, but in my appreciation for the political philosophers of the Enlightenment whose ideas laid the groundwork for the American experiment. In 2009, I married a man from Kenya. From the day in Nairobi when a consular official told me that my husband — then my boyfriend — would be unable to get a visa to visit me in the U.S., I felt that my own rights were being abrogated. My husband and I were considered guilty until proven innocent. Even on the forms we had to fill out, the language sounded arrogant: Fiances or spouses applying for visas are called “beneficiaries.” The process is expensive and has been dragging on for years. A mistake on an application might mean I won’t see my husband for months, or that he’s unable to travel to his home country for fear that he won’t be able to return. I began to see the America that people in other nations see, and it was completely different from the land of my childhood.

I cannot count the times I’ve said to my husband, “America really isn’t like this.”

I’m not sure he believes me. I don’t know if I believe it myself.

By the time we started the process, the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service), had receded into history. Since the Bush administration, two separate agencies handle immigration. The U.S. Department of State issues visas, but the bulk of the work is done by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which is part of the Department of Homeland Security, established after 9/11.

The State Department, not always a model of efficiency in its consular sections abroad, has set up a system with a 24-hour turnaround by email in the U.S. By contrast, USCIS is notoriously hard to reach by telephone and slow to respond to queries. It is impossible to speak to anyone who actually handles paperwork; all calls are routed to a call center. Processing times stretch into months or years. Horror stories of punitive measures triggered by a change of address, or a lost submission, are common.

In short, the U.S. immigration system functions like bureaucracies in countries we consider undemocratic, inefficient and oppressive: the former Soviet Union perhaps or an African nation mired in corruption. High fees and long waits are a substantial burden to many families, and create a class of people who are in America but not completely of it. Part of the problem is budgetary, but the basis of the USCIS funding problem seems to be the underlying attitude that immigration is not a normal function of government, and that immigrants add nothing of value to American life, even if they happen to be Internet entrepreneurs or internationally recognized scientists.

“The U.S. has this weird provision,” Jones-Correa said. “The USCIS has to be self-funded, through the fees from the naturalization process and the green card process. Immigrants themselves, and their family members, pay for the program’s budget. There is no other country for which that’s the case.”Some of the burdensome paperwork began at a time when people desperately wanted to come to the U.S. Now, stories of immigrants returning to their native countries are becoming more common. That is, in fact, what Anzor Tsarnaev and Zubeidat Tsarnaeva did when they divorced in 2011, leaving their son Dzhokhar in the care of his older brother Tamerlan.

In the recent film “The Reluctant Fundamentalist,” based on the novel by Mohsin Hamid, that is exactly the decision made by the young protagonist, an up and coming associate at a Goldman Sachs-like investment firm. It is not inconceivable that, at some future date, the U.S. itself might face the brain drain that other countries worry about. Life is still safer here, for most people. But a tad less arrogance might be in order.

Yet there is a model for immigrant integration in the U.S., according to Jones-Correa. The U.S. refugee program, which admits 70,000 people a year, helps fund integration via local nonprofits, settling refugees in communities and helping them with education and employment.

The U.S. refugee program looks like what countries such as Britain, Canada and the Netherlands do for all immigrants, Jones-Correa said.

“If you think of citizenship as a prize, something that people have to prove themselves to get, then you make it difficult, create a set of hurdles,” Jones-Correa said. “It’s as if you’re saying, prove that you really want it. How much are you willing to pay for it?”

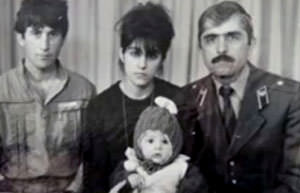

How much are you willing to pay for it? Instead of voting rights, immigrants to America have TV and the Internet, testosterone-charged fantasies of jihad for the boys, materialistic Kardashian bingeing for the girls. Is it surprising that Anzor’s wife — photos show her as a good-looking woman with a punkish Amy Winehouse beehive in the ’80s before her adoption of hijab — was busted for shoplifting $1,624 worth of clothes at Lord & Taylor?

“I don’t think the issue is so much border security, which the current bill in Congress strengthens even further,” Jones-Correa said. “The more likely threat is that people aren’t reaching their full potential. You end up with a generation of kids growing up in the U.S. who can’t graduate from universities, can’t fully contribute. When you can’t fully contribute and you feel that your options are shut off, you begin looking at other options.”

Apparently, that’s what Tamerlan Tsarnaev did in January 2012, when he returned to Dagestan. He spent six months in a community marked by poverty and a decade of low-level insurgency against Russia, and there is speculation that he also traveled to Chechnya.

In 2011, according to Time magazine, the Russian Federal Security Service had contacted the FBI, asking agents to question Tsarnaev. In an April 19 statement, the FBI said it interviewed Tsarnaev and researched records, but “did not find any terrorism activity, domestic or foreign.”

Perhaps this is why Russia allowed Tsarnaev to return to Dagestan the following year. To his relatives in Dagestan, Tsarnaev must have sounded like a typically naive young American. An unnamed source recalled attending a beach barbecue with Tsarnaev, who called Dagestan’s insurgency “a holy war.”

“Some of our guys started telling him that this is no holy war, that it’s just banditry and has nothing in common with holy war,” the man told Time correspondent Simon Shuster. “Muslims here are killing Muslims. That’s what we explained to him.”

Tamerlan Tsarnaev returned to the U.S. after spending most of his time helping his father build a perfume store and sleeping a lot. By most accounts, he failed to find the jihad he was looking for.

Writing about the Boston Marathon bombings in The New Yorker on April 25, John Cassidy proposed “a little mental experiment”:

Imagine, for a moment, that the Tsarnaev brothers, instead of packing a couple of pressure cookers loaded with nails and explosives into their backpacks a week ago Monday, had stuffed inside their coats two assault rifles — Bushmaster AR-15s, say, of the type that Adam Lanza used in Newtown.

What would have been different? Cassidy asked. AR-15s can fire up to 45 rounds a minute, and at close range they can tear apart a human body. If the Tsarnaevs had opened fire near the finish line, they might have killed dozens of spectators and runners.

More people would be dead and gun control legislation might have passed.

Tamerlan Tsarnaev might have been captured alive.

No evidence has surfaced showing that Tamerlan Tsarnaev was trained by or in contact with terrorist organizations, but as Cassidy points out, that doesn’t mean the Boston bombings weren’t terrorist acts. Still, Cassidy’s thought experiment is an interesting one, both for what it states and what it implies.

Investigations may yet reveal that Tsarnaev had contact with terrorists, but it’s more probable that he was just another angry young man in our brave new America, a burgeoning dystopia where mass murder suddenly seems like a weekly occurrence. Two researchers, Deniese Kennedy-Kollar of Molloy College and Christopher A.D. Charles of Monroe College, published a paper in The Southwest Journal of Criminal Justice that went deeper than police characterizations of Lanza, who shot 26 children at Sandy Hook Elementary School, as a video game obsessed “glory killer.”

Their study collected biographical information for 28 men who have committed mass murder in the United States since the 1970s. Only rarely were mass murderers considered mentally ill. The majority, 71 percent, demonstrated financial stressors; 61 percent showed social stressors; 25 percent experienced romantic stressors; but only 32 percent had psychological stressors.

Citing a wide range of literature, the researchers reported that they were led to explore mass murder as an attempt to lay claim to a masculine identity the killers felt had been damaged or denied them, yet to which they felt entitled as males in American culture.It’s one of those twists of fate that the Boston bombings happened as the immigration debate heated up in Congress. Seizing the opportunity to block reform, Charles Grassley of Iowa, the ranking Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee, and Rand Paul, the Republican senator from Kentucky, brandished the security shibboleth, calling for “triggers” that would allow reforms only after security measures have been proven effective. Appearing before the Senate, Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano countered by testifying that the proposed bill would, in fact, provide additional security measures, and that blocking it would be counterproductive in the war against terror.

At a hearing on the legislation April 22, Democrat Patrick Leahy of Vermont, the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, openly criticized immigration opponents for “exploiting” the Boston Marathon bombings to delay action on immigration reform. “Let no one be so cruel as to try to use the heinous acts of these two young men last week to derail the dreams and futures of millions of hardworking people,” Leahy said.

Leahy might also have noted that it is in America’s self-interest to bring the country’s immigration system up to the standard set by nations such as Canada and Britain. That would mean paying attention to the advice of immigration experts Papademetriou and Kober, who recommended addressing “sets of circumstances” such as poverty and lack of education that apply to a broad swath of the population, rather than the problems of immigrants per se. Their strategy is aimed at defusing anti-immigrant sentiment, but it’s also an acknowledgement that there will never be enough prisons, even in America, to save us from a global generation of young men and women who are both jobless and hopeless.

When people feel their options are shut off, they begin looking at other options. For Tamerlan Tsarnaev, the only option he saw might have been the amateurish terrorism that left us staring at columns of smoke in disbelief. His citizenship papers were stalled, but like Adam Lanza, the 20-year-old video game obsessive who found a way to beat the numbers and join the pantheon of antiheroes, Tamerlan Tsarnaev just might have turned out to be a real American boy after all.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.