Ralph Nader vs. the FEC

Nader is suing the Federal Election Commission for not investigating the law firms that allegedly worked on behalf of the Democratic National Committee in a coordinated effort to obstruct his bid for the presidency in 2004. Nader is suing the Federal Election Commission for not investigating the law firms that allegedly worked on behalf of the DNC in a coordinated effort to obstruct his 2004 bid for the presidency.

By Thomas Hedges, Center for Study of Responsive LawEditor’s note: The author of this article works for Ralph Nader, which presents an obvious bias. However, we think the story remains instructive, fact-based and of concern to our readers. The reporter contacted the Federal Election Commission for its side of the story, but the FEC declined to comment.

Ralph Nader is suing the Federal Election Commission for not investigating the law firms that allegedly worked on behalf of the Democratic National Committee in a coordinated effort to obstruct his bid for the presidency in 2004.

Nader’s attorney, Oliver Hall, met FEC representatives in the federal Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia on Monday morning to challenge the agency’s decision to dismiss a complaint Nader submitted in May 2008.

The lawsuit is the latest development in an ongoing struggle between Nader and DNC sympathizers who, he says, continue to harass him with litigation almost 10 years after the election. Among them are 53 law firms that challenged Nader’s nomination petitions in 18 states with the alleged intent of distracting the candidate from his run for the presidency. Nader charges that the Democratic National Committee coordinated with law firms as well as the Kerry-Edwards 2004 campaign committee.

The FEC dismissed Nader’s complaint in April 2010, without serving it on any of the law firm respondents, on the grounds that the commission had no reason to believe the firms broke the law.

Nader argues that the FEC violated the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 (FECA), which requires the agency to serve his complaint on the respondent parties and conduct an investigation if evidence provides reason to believe they may have violated FECA. The FEC, Nader says, never contacted those who committed the alleged violations and ignored emails and other evidence demonstrating that the DNC and Kerry-Edwards campaign coordinated and participated in the effort to frustrate the Nader campaign.

In the complaint, Hall notes that some 35 organizers met at a hotel in Boston to plan the siege on Nader’s bid in July 2004. There were representatives from advocacy groups, law firms and the DNC, which paid for the meeting. The memo that came out of that meeting told leaders to convince Nader supporters that he was “in bed with Republicans.” That phrase was hammered into voters’ minds, Hall argues, for months until the election.

In August 2004, a representative from pro-Kerry group The Ballot Project, Toby Moffett, told a Washington Post reporter that law firms had provided some $2 million in legal services, which were never reported as campaign contributions.

Many DNC affiliates, such as Jack Corrigan and Judy Reardon, promoted and sometimes wrote complaints for law firms. In Maine, Democratic Party Chair Dorothy Melanson testified in court that the DNC officials had encouraged her to file a challenge against Nader and said they would pay for the costs of her lawsuit.

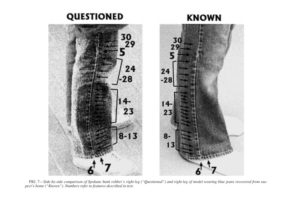

Some of the groups that aligned themselves with the DNC, Hall says, harassed Nader. They sabotaged his nomination petitions, disrupted conventions and falsely threatened petition circulators. One firm retained by the DNC, Reed Smith, has frozen Nader’s bank account since 2008, asking for $81,000 in litigation costs it claims it incurred in challenging Nader’s Pennsylvania nomination petitions. A grand jury investigation by Pennsylvania’s then-Attorney General Tom Corbett later revealed that state employees illegally prepared a substantial portion of the challenge at taxpayer expense.

The FEC, which has a stated policy addressing ballot challenges, has ignored the alleged abuse.

“A candidate’s attempt to force an election opponent off the ballot so that the electorate does not have an opportunity to vote for that opponent,” it reads, “is as much an effort to influence an election as is a campaign advertisement derogating that opponent.”

Despite its policy, coupled with the evidence, the FEC says it had no reason to believe the pro-Kerry groups coordinated with the Kerry-Edwards committee or the DNC. The agency also said the lawyers may have worked pro bono and qualified for FECA’s “volunteer” exception.

But evidence suggests that these lawyers were on company payroll, used company office supplies and were sometimes paid by the DNC. All of these services, according to FECA, count as campaign contributions and must be reported to the FEC.

The FEC declined to comment on these allegations.

In its brief, the FEC focuses more on Nader’s standing, which, it says, he lacks. A remand of the lower court’s decision to allow for the dismissal of the complaint, FEC attorney Seth Nesin said, does not provide Nader with any vital information that pertains to his line of work. There is no evidence that the disclosure of these sources of contributions, he argued, would be relevant to his career.

But Nader, Hall argues, has been writing about these sorts of issues since the 1950s.

“He’s still very much engaged in that advocacy,” Hall told me over the phone. “The information is also useful to him in his efforts to repair the damage done to his reputation by the respondent parties in this case, who falsely accused him of fraud in states all across the country and in national newspapers like The New York Times and The Washington Post.

“The idea that this information is of no use to Ralph Nader is absurd on its face,” Hall said, “and it’s contradicted by the evidence in the record. It demonstrates that the FEC can’t defend this case … and all that’s left is for it to misrepresent the law and the record.”

The aggravating back-and-forth litigation between Nader and the respondent parties, Hall says, reflects the draconian grip Democrats and Republicans hold on the election process.

“Not since Eugene Debs won a million votes from a federal prison cell in 1920 has there been such a direct and concerted effort to prevent an American citizen from running for public office,” he says.

“This case shows the way that the discriminatory, self-serving anti-competitive system that the Republicans and Democrats have enacted can be exploited whenever one of the parties decides that it doesn’t want voters to have the choice to vote for a competitor. It’s rife with the possibility for abuse as Ralph Nader was subjected to it in 2004. It invites these parties to file these frivolous lawsuits … and nobody has the capacity to defend against 29 different complaints in 18 different states and at the same time run an effective national campaign.”

And now, Hall says, “we have to defend our standing, the idea that we even have a right to be heard in court. That we would even have to defend against that is an indication of how far we have to go before we can have a robust democracy and a free and open competitive election process in this country.”

This article was made possible by the Center for Study of Responsive Law.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.