Paul Cummins: The Elephant in the Classroom

In this excerpt from his new book, "Two Americas, Two Educations," the co-founder of the trailblazing Crossroads School in Santa Monica, Calif., argues that America contradicts its purported belief in the value of education by egregiously underfunding it.

Editor’s note: The following is the first chapter of Paul Cummins’ upcoming book, “Two Americas, Two Educations: Funding Quality Schools for All Students” (Red Hen Press, January 2007).

In this excerpt, Cummins, the co-founder of the trailblazing Crossroads School in Santa Monica, Calif., argues that America contradicts its purported belief in the value of education by egregiously underfunding it.

There is one issue all Americans agree upon. We all say we believe in the value of education. Whatever our political or economic views, whatever our varied cultural orientations and tastes, whatever our religious convictions, we all believe that high-quality education is critical to the individual and to society. This means that we share a fundamental belief that public education has the capacity to mold the nation’s young people into capable, productive, and decent citizens, and that this accomplishment is one of our country’s highest public goals, if not the supreme goal.

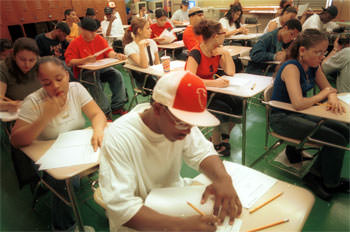

Yet many of our schools are failing. How has this tragic disconnect occurred? Daily in our newspapers we read of declining test scores, overcrowded schools, gangs and vandalism, drugs and violence, deteriorating school grounds and buildings, alienated youth who are dropping out in droves. Yet, during much of this time, say, 1970-2005, the U.S. economy has grown and flourished. California, whose economy is larger than that of most nations in the world, is a case in point. In the 1970s, California public schools were judged to be excellent. Per-pupil spending in California schools was consistently above the national average. Then several major challenges (some would say disasters) confronted the state, and thus the schools, simultaneously.

California began receiving an unprecedented influx of immigrants, who now constitute 10 percent of the population (as opposed to the national average of 5 percent). Many of the new immigrants, who spoke little English, enrolled their children in the public schools. (Latino children now represent 45.8 percent of California’s public schools and 72.8 percent of the Los Angeles Unified School District.) In addition, California has one of the highest percentages in the nation of children who live in poverty, and this condition is worsening.

A second blow was the passage in 1978 of Proposition 13, a statewide referendum that deliberately lowered the state’s property tax revenue. Gradually California’s previously admirable per-pupil funding fell to third lowest in the nation — where it has remained. English language learners and children living in poverty are simply more expensive to educate. California is not the only state to fail to respond to this demand upon its resources. California is a blatant example, but the rest of the nation is also failing. Not everything is a matter of funding, but funding is a crucial issue. While some conservatives, such as Eric Hanusher, point out that correlating funding to achievement is murky 1, the noted educator Alfie Kohn points out that no one in the suburbs says, “Money isn’t correlated with achievement, so here, you may as well take some of this extra cash off our hands.” 2 Even the most cautious of studies indicates that funding levels are crucial to student performance. In a recent study, Anne L. Jefferson concludes: “Overall, the literature indicates that the amount of money cannot be removed as an important variable in the education achievement of students. Furthermore, the literature clearly points to usage of money allocated as key.” 3 Our nation’s inner-city and low-income neighborhoods and impoverished rural communities are being grossly ignored, under funded, and thereby harmed. Writing about an often ignored segment of our nation — that is, poor rural areas — Cynthia Duncan states that nearly nine million Americans live in poverty in rural areas and one-third of the nine million live in communities with persistently high poverty rates. These children are virtually invisible; without a high-quality education, their chances to escape the crippling effects of poverty are almost nil. As Duncan writes, “Education is, just as the American Dream has always implied, an avenue for upward mobility for individuals. But most schools in America’s poor communities do not offer that opportunity.” 4

The nation also faces a growing sense that democracy at home is under siege. No matter how much they may admire billionaire captains of industry, most Americans still cherish a belief in a just society that is able to maintain at least some equality or proportionality of opportunity, and appropriateness in the distribution of wealth. Yet, as we have seen — and as this book argues — there has been a relatively recent and very rapid increase in the disparity of wealth in America. This growing gap plays itself out in our national education systems, where we see the growth of two distinct polarities: two Americas, two educations. On the one hand we see private schools and wealthy neighborhood public schools that offer beautiful and functional campuses, comprehensive and enriched curricula, and excellent teaching conditions. On the other hand, we find many inner-city and low-income neighborhood public schools with inadequate facilities, overcrowded classrooms, undernourished curricula, and overall miserable teaching conditions. And though some would argue otherwise, the fact that the well-to-do schools are often spending three times more than the others is, I believe, a major reason for the differences in quality, and hence opportunity, for the children. There is an elephant in the living room that most legislators, citizens, and even educators are ignoring: we are not properly funding our schools. Though we may wish it would, this elephant will not go away. Furthermore, there is a reason for this situation that we have not yet fully grasped.

Some will argue that educational spending has grown along with everything else — so what’s the problem? They will often add that it must therefore be poor management, bureaucracy, progressively oriented college education departments, or whatever, that have rendered our schools inadequate, not a lack of funds. I disagree. What we have not grasped is that in urban areas and elsewhere there has been a massive increase in social problems that has been neither fully acknowledged nor confronted.

Notes:

1 Eric Hanusher, as quoted in Alfie Kohn, “The Schools Our Children Deserve” (New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1999), p. 247. 2 Ibid. 3 Anne L. Jefferson, “Student Performance: Is More Money the Answer?” (Journal of Education Finance, Fall 2002), pp. 111-124. 4 Cynthia Duncan, “Worlds Apart: Why Poverty Persists in Rural America” (Cambridge, Mass.: Yale University Press, 2000), p. 205.This proliferation of social problems receives lip service, but few realize the impact of these problems upon schools. Consider: a massive infusion of non-English-speaking students — in some schools more than 50 languages are spoken. Consider: in some neighborhoods there are two and three families living in one- or two-bedroom apartments whose conditions afford students no possibility of studying or doing homework. Consider: in many of these neighborhoods gangs rule, and from 3 p.m. to darkness the streets and parks are unsafe. Where then do inner-city children go and what can they do? Consider: in many neighborhoods drug dealing, crime, and violence are daily occurrences; consequently many children come to school frightened, sometimes abused, or physically undernourished. The pitifully understaffed schools are expected to deal with these problems as well as teaching academic skills — and, frequently, all of this is expected to be carried out in overcrowded classrooms.

The implications and requirements that these relatively new social conditions impose on schools are enormous. To make serious improvements would necessitate:

1. in many middle schools and high schools, cutting class size in half, which would necessitate 2. hiring 100 percent more teachers — which would necessitate 3. repairing campuses and building more schools and classrooms and 4. hiring more counselors, special education specialists, ESL teachers and 5. creating after-school programs for latchkey children and youth.

That would be just a start. Yet each of these requirements would require substantial new funding. There’s that elephant.

But for some reason the elephant seems to be invisible. Poverty and its companions, poor health systems, poor housing, and poor schools, seem to be off society’s radar screen. Forty-five years ago Michael Harrington noted that “The other America, the America of poverty, is hidden today in a way that it never was before. Its millions are socially invisible to the rest of us.” 5 Similarly, a year before Harrington, James Bryant Conant argued in his Slums and Suburbs that “The contrast in money available to schools in a wealthy suburb and to the schools in a large city jolts one’s notions of the meaning of equality of opportunity.” 6

As concerned as Conant and Harrington may have been in 1961-62, matters have worsened since then. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that inner-city children, rather than the smaller per-pupil funding they receive, actually require more funds in order to compensate for their social deprivation. Bruce D. Baker, a reviewer of several such studies, concludes that children from economically deprived backgrounds would require 35 percent more spending than the average costs, and children with limited English proficiency will require spending around 100 percent above average.7 Anything short of this amount is likely to perpetuate failure.

A recent Rand Corporation study that was commissioned to discover the complex reasons behind California’s underperformance in K-12 education reached several important conclusions.8 First, California’s per-pupil expenditures were third lowest in the nation, as mentioned earlier in this chapter. Reasoning that perhaps one explanation for California’s difficulties could be found in its disproportionate number of immigrants, the Rand economists statistically corrected for this disparity among the states. This time, California’s expenditures came out dead last! But then a completely unexpected result emerged: Texas, with a similarly large minority population, which had languished along with California near the bottom of the per-pupil spending rankings, vaulted to first place when the data was adjusted for minority enrollments. In other words, unlike California, Texas has actually faced up to the challenge of trying to provide a decent education to non-English-speaking children and children of poverty, primarily by means of universal preschool for low-income children. As Rand’s lead economist explained in a recent briefing, this achievement was driven almost entirely by Texas’ business leaders who, to their credit, realized that providing a substandard education to Texas’ low-income and non-English-speaking students would in the long run immensely impair Texas’ economic prospects and its competitiveness. It does not even require an extra helping of the milk of human kindness to see that funding public education adequately is the correct thing; in the case of the Texas business community, even simple self-interest will do.

The consequences attached to failing or succeeding in this gigantic effort are enormous. In a real sense, both our nation’s soul and its essential viability are at stake. If we become a hopelessly and irreversibly two-tiered society with the few very rich flourishing and the many poor living in degraded conditions, we will have shattered the American dream of a democratic, just, and fair society. We will have become an oligarchy-aristocracy-plutocracy, but will no longer be a democracy. How we regard and treat our schools will be a major determinant of what path we choose. We are already well down the road towards oligarchy; it is almost too late to change. Almost.

Notes:

5 Michael Harrington, “The Other America” (New York, Penguin Books, 1962), p. 3. 6 James Bryant Conant, “Slums and Suburbs” (New York: Signet, 1961), p. 10. 7 Bruce D. Baker, “The Emerging Shape of Educational Adequacy” (Journal of Education Finance, Winter 2005), pp. 259-287. 8 Stephen J. Carroll et al., “California’s K-12 Public Schools: How Are They Doing?” (The Rand Corporation, RAND/MG-186-EDU, 2005).

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.