Obscenity

To suddenly realize at age 7 that balls and testicles referred to the same thing was a real eye-opener for me It meant that the obscenity of the word balls was not intrinsic to the thing that it referred to, but rather to the word itself.

“[N]ever forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was ‘legal.’ ” — Martin Luther King Jr.

It was 1973 and I was 7 and had just figured out there was no such thing as obscenity. And while I was being dragged out of my bedroom, away from my open window, down the hallway and through the house by my mother, my fist still clutching the magic marker that I’d used to draw a mustache on myself when I first heard her slippers charging up the stairs like fuzzy mallets, I sort of knew that I wasn’t going to save the world that day. In fact, the overly flamboyant French accent that I used to confront her with when she burst into my room didn’t fool her into thinking I was somebody else, partly because the phrase Bidet au gratin, mademoiselle — déjà vu, déjà vu! made absolutely no sense whatsoever and partly, I assumed, because the mustache that I’d drawn on myself, as confirmed by the dining room mirror that I passed on my way into the kitchen, looked much more Zapata than Chevalier.

“Senorita! Mi sancho pantza esta muy mal! Y donde, por favor! Qué guapo tamale? Arriba! Arriba!” Slam! went the back door, and there I stood, no cap for my marker, surrounded by 100 paper airplanes bearing the words FUCK YOUR ASS written in big crazy letters, a dule of dead doves inspiring to no one.

***

I drove out to the Beverly Hills Hotel, an hour and a half in traffic, while the oily Tuesday afternoon sun melted into the toxic rainbow sherbet that is the Los Angeles sunset, for the singular purpose of snubbing Ken Starr. This was in 2006. I’d been imagining the scene for weeks, the sophisticated crowd, the sound of Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five” sashaying through the room like a sumptuous Pan Am stewardess, the tap on the shoulder, me turning with my glass of Romanée-Conti to see the man standing there completely scentless and emitting no heat, his face split into the sort of well-rehearsed smile that comes from decades of overachievement and never joy. He extends his hand. I look down at his chubby fingers, the manicured fingernails as shiny as wet cough drops, the soft puff pastry of a palm, the gleam of a watchband roughly approximating the value of Rhode Island. I do the classic gasp-chuckle of sitcom disbelief and turn back around, shaking my head. Starr’s face begins to redden as if he’d just stepped into a freezing wind. I continue my conversation, my voice elevated just slightly to be heard over the shrill whistle of steam coming out of his ears only moments before his head explodes like a hot coconut. Applause. Curtain.

So why would Ken Starr ever want to shake my hand, you ask?

Well, as a freelance artist I’ve always had to take in extra laundry to pay my bills and a couple of years ago I took in a big stinky load from the Los Angeles Daily Journal, the pre-eminent law newspaper of Southern California. The Journal is sometimes thought of as the Hillcrest Country Club of L.A. papers due to the exclusionary nature of its subscription-only availability, its content too hoity-toity to fraternize with other publications at newsstands, its Web content secured behind a pay wall like the sort of pornography that no decent person hoping to remain decent would want to see. My assignment was to draw 100 portraits for the paper’s annual supplement dedicated to recognizing the top lawyers of California, and Starr was one of them. So were other celebrities such as Gloria Allred, of O.J. Simpson and Amber Frey fame; Harvey Levin, of “The People’s Court” and TMZ; and Jerry Brown, of Linda Ronstadt and Governor Moonbeam.

***

The idea to save the world by writing FUCK YOUR ASS on 100 pieces of paper, folding them into airplanes and floating them out my bedroom window like dandelion spores came to me over Memorial Day weekend about 15 minutes after I started horsing around with my older brother Jeff in the back seat of my mother’s station wagon. The car was parked in the driveway and he and I had ducked inside to escape a flurry of wasps whose hive we had dislodged while helping our stepfather put in an air conditioner. Jeff was trying to wrestle me into a headlock so that he could spit an ice cube down the back of my shirt, and I was trying to pin him to the opposing wall of the interior cab with my feet when I accidentally kicked him so hard in the nuts that I swear he blacked out for a full 30 seconds.

Ten minutes later I was handcuffed to the neighbor’s fence with no pants on while Jeff, refusing to hand over the key, explained to my stepfather how I, without provocation, had kicked him in the balls.

“Testicles,” corrected my stepfather, narrowing his eyes like a marine biologist who had just pointed out someone’s misclassification of a dolphin as a porpoise.

“Huh?” said my brother.

“They’re testicles, not balls.”

“Well, aren’t they the same thing?”

“Yeah,” said my stepfather, “of course they are, but just call them testicles. Saying balls upsets your mother.”

***

“We also have a party at the Beverly Hills Hotel when the issue is published,” I was told by the Journal’s editor when the job was pitched to me. “We’re going to have all the original drawings put in frames and give them to the lawyers as little presents,” he said, “and you can be at the party. I’m sure they’ll all want to shake your hand!” The whole time he was talking I was trying to figure out how I was going to get the words “fucking” and “asshole” into the Starr portrait with the same deft hand that Hirschfeld used to get in his “Nina.”

Taking the ticket stub from the valet and throwing on my jacket, I straightened my tie and walked through the hotel lobby in search of the concierge to help me find the room where I imagined Starr was eating enough cocktail weenies to verge on some infringement of Megan’s Law. Moments later I walked into the Sunset Room and, having had the point of my HB Staedtler pencil up the nose and inside the pupils and along the lips of every lawyer’s face I saw, suddenly had the uneasy feeling that I was a voyeuristic pervert who had been watching these people through a two-way mirror for the last six weeks. After all, these were the facial features I’d caressed into being with all the slow and deliberate attention to detail that a cannibal might use to eviscerate his victims into a delectable dish, only I had done it in reverse.

I felt a tap on my shoulder and turned around. “The portraits look great!” said the editor, having appeared out of nowhere to shake my hand. “Did you see them?”

“Yeah, on the way in,” I said, referring to the table just outside the entrance where all 100 framed drawings that I’d done sat near a large sign requesting that each lawyer wait until the end of the evening before retrieving his or her portrait to take home. “By the way,” I said, “I never asked, how did you guys determine who belonged on the list of top 100? Given the fact that the average person finds lawyers, as a group, somewhat despicable –individually, they find them repulsive — I’m guessing that it wasn’t a contest that had been put to a public vote.”

“It was very unscientific,” he said, appearing uncertain as to whether he should be offended by my characterization of his bread and butter as repulsive. “Me and the other editors got together every morning for a couple months and talked about who should be on the list and who shouldn’t.”

Then he excused himself, leaving me to realize for the first time that rather than being hired merely as a portrait artist, I’d been appointed as a court painter whose responsibility was to glorify the members of some royal family, or, in this case, to exalt the equivalent of the football team for a high school newspaper, the primary purpose of which was to publish insular stories that celebrated the victories of all the prom kings, prom queens and star athletes toiling in the time-honored profession of high class hoity-toitiness. And as it was with every high school dance that I’d ever attended, the cool kids spoke gregariously with one another. The effluvium of their charm and the gracefulness of their dancing turned my blood cold. I eventually found myself standing all alone against the wall with my hands in my pockets, waiting for the room to empty.

***

To suddenly realize at age 7 that balls and testicles referred to the same thing was a real eye-opener for me. It meant that the obscenity of the word balls was not intrinsic to the thing that it referred to, but rather to the word itself — to the physicality of the word, to how it looked and sounded. How else to explain the acceptability of the word testicles, which referred to the same thing that the word balls did and was not obscene? To believe in obscenity, I figured, was to set up a scenario where it was OK to harbor a severe prejudice against the sight and sound of a word, which would be nothing less abhorrent than reinforcing the bogus idea that a thing — anything! — could be obscene merely by being seen or heard.

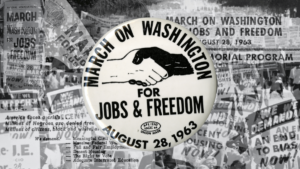

The debate about the obscenity of words seemed no different to me from the civil rights era debates about what freedom and justice and equality should look like. I was inspired. African-Americans were perceived as obscene by white society for occupying bus seats and lunch counters and schools. Likewise, I decided that it was time to demand a new emancipation for persecuted words. It was time to demand equal rights for all speech because all speech was connected to all ideas, which were connected to all deeds, which were connected to all acts, which were connected to all hopes and dreams, both realized and not.

It was time to reconfigure the law and to become a hero whose portrait I imagined would grace the halls of justice one day and inspire all whose eyes fell upon it.

***

Standing to leave at around midnight, having thrown back my last swig of red wine, I stumbled through the foyer of the Sunset Room just as the cleanup staff began to bunch up the soiled tablecloths and remove the chairs and scratch their heads and wonder what they were going to do with all the framed portraits sitting untouched in front of them. Thinking back 33 years, I approached the table to help them, remembering how I had been tasked by my mother with the chore of picking up the trash of my idealism, wondering the whole time if some things fly only because they exist in a vacuum and aren’t really flying at all.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.