Obfuscating Unemployment

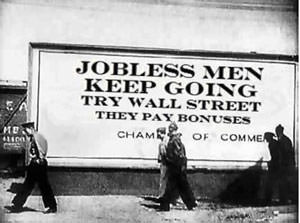

During the Great Depression, high rates of unemployment prevailed for 11 years The experience of seeing a free market system drive itself into a rut that it cannot pull itself out of is nothing new And we have long known the solutionThe experience of seeing a free market system drive itself into a rut that it cannot pull itself out of is nothing new.

David Leonhardt of The New York Times wonders why unemployment has remained so high for so long. At first, it seems to him that it is because American employers are too strong and American workers too weak. But after contemplating the matter further, he discovers his own folly.

Leonhardt starts with unions. Unions are good, he explains, because they give workers bargaining power. But strengthening unions would nevertheless be difficult because, according to Leonhardt, too many unions have hurt the companies for which their members work. And after consulting with a Harvard economist, Leonhardt discovers two more reasons why unemployment is the fault of the unemployed: Disability insurance gives workers an incentive not to work, and low levels of education make them unemployable.

The example of a harmful union that Leonhardt cites is the auto workers union. As if it was the union that forced GM to produce cars that consumers did not want to buy, or as if with the same union Ford was unable to thrive. Any explanation of the rate of unemployment that involves unions, disability insurance or education is in any case laughable simply because none of these changed over the last two years, during which time joblessness surged. The highest rate of unemployment is currently among construction workers. Would there have been more new housing or schools if their unions were more compliant, their level of education higher or disability insurance less generous?

During the Great Depression, high rates of unemployment prevailed for 11 years and declined only when the U.S. entered World War II. The experience of seeing a free market system drive itself into a rut that it cannot pull itself out of is nothing new. And thanks to John Maynard Keynes’ explanation of how a market system actually works, we also know what the solution is.

As Keynes explained it, a market system must have a high level of investors’ optimism to boost the demand for goods and services to the full-employment level; the high-tech bubble of the Clinton years and the housing bubble of the Bush years are two recent examples. But when private investment is sluggish, it is the duty of the government to invest. President Dwight Eisenhower’s National Defense Education Act and National Defense Highway Act are examples of what the government can do not only to keep employment high, but to create things that people actually need. Of course, the top marginal tax rate during Eisenhower’s two terms in office was 91 percent, which explains how he could do it without creating an unfathomable deficit. The highest deficit during the Eisenhower years was 2.6 percent of GDP, whereas in 2010 it was 10.6 percent.

President Barack Obama presents the extension of the Bush tax cuts, and particularly the Social Security tax cut, as a job stimulus. But with the deficit being so large, the net effect on jobs will probably be a loss.

Whether or not the deficit should matter, the fact is that members of the public are concerned about it, and, therefore, it does. Because of this concern the tax cuts will bring about reductions in government services, and these will mean higher out-of-pocket expenses for families. If schools do not have music teachers, parents who can afford to will have to pay for music lessons themselves. When tuition increases, parents who can afford to will have to pay more for college, too. Where would the gain in jobs come from, then? And because it decreases the solvency of the Social Security system, the cut in the payroll tax will probably lead those who are concerned about retirement, and who have the means, to save more and spend less.

Furthermore, the public demand for closing the deficit is in itself a source of uncertainty that an economy with gloomy investors doesn’t need. To what extent the deficit will be closed by a reduction in services, an increase in taxes or the growth of the economy can’t, of course, be known; this is why the tax cuts are destabilizing.

Since unemployment is a regular feature of a free market system, let’s not mystify it. And let’s also not pretend that the cure for it is as mysterious as the cure for cancer, when all we need is to tax and spend.

Moshe Adler teaches economics at Columbia University and at the Harry Van Arsdale Center for Labor Studies at Empire State College. He is the author of “Economics for the Rest of Us: Debunking the Science That Makes Life Dismal.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.