Obama’s ‘Singular’ Mother

The key to understanding the disciplined and often impassive 44th president is his mother, as Janny Scott, a reporter for The New York Times, decisively demonstrates in her new biography, "A Singular Woman."The key to understanding the disciplined and often impassive 44th president is his mother.

This review is from a syndication service of The Washington Post.

The key to understanding the disciplined and often impassive 44th president is his mother, as Janny Scott, a reporter for the New York Times, decisively demonstrates in her new biography, “A Singular Woman.”

The solicitousness that can anger liberals, the deliberativeness that can infuriate conservatives, the unusual belief in both empirical research and human goodness, the wicked cutting humor — all of it comes from a woman who defied conventions.

A bookish outsider and only child, Ann Dunham was plunked down in Hawaii the year after it became a state by her restless father and her resolute mother. In her first months as a college freshman, at 17 years old, she got pregnant by her first boyfriend, an older student from Kenya named Barack Hussein Obama, who left her when the baby was 11 months old. Twice she married men from different cultures and races, then divorced them. With the help of her parents, she raised two biracial children as a single mother on the Pacific islands of two nations, got degrees in math and anthropology, spent years in peasant villages studying Javanese cottage industries, and pieced together grants and development work to make money and provide for her children’s education. Colleagues credit her with helping pioneer microcredit as a tool for lifting women out of poverty.

Through Scott’s meticulous reporting, archival research and extensive interviews with Dunham’s colleagues, friends and family, including the president and his sister, a portrait emerges of a woman who is both disciplined and disorganized, blunt-spoken and empathetic, driven and devoted to her children, even as she ruefully admits her failings and frets over her distance from them.

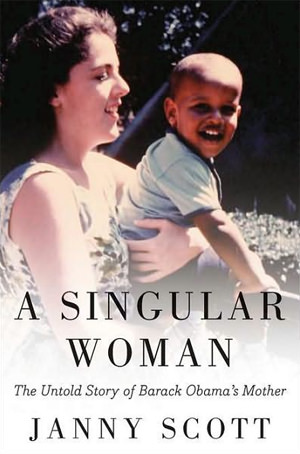

A Singular Woman: The Untold Story of Barack Obama’s Mother

By Janny Scott

Riverhead Hardcover, 384 pages

“She was a very strong person in her own way,” the president told Scott, “able to bounce back from setbacks, persistent — the fact that she ended up finishing her dissertation. But despite all those strengths, she was not a well-organized person. And that disorganization, you know, spilled over.” He said she took too much for granted that everything would just work out, and that had it not been for his grandparents “there to provide that floor, I think our young lives could have been much more chaotic than they were.”

The same global perspective that lent Barack an Indonesian calm and an outsider’s curiosity also led him to seek a more traditional family life. And so he chose Michelle Robinson, a woman who had returned home to the South Side of Chicago after Princeton and Harvard. Ann Dunham said of Michelle, in a letter to a friend, “She is intelligent, very tall (6’1″), not beautiful but quite attractive.” She noted her Ivy League degrees and added: “But she has spent most of her life in Chicago” and was “a little provincial and not as international as Barry,” as the young Barack was known.

“She felt a little bit wistful or sad that Barack had essentially moved to Chicago and chosen to take on a really strongly identified black identity,” recalled Don Johnston, Dunham’s colleague at Bank Rakyat Indonesia. That identity, she felt, “had not really been part of who he was when he was growing up.” Dunham thought he was making what Johnston called “a professional choice” to strongly identify as black. “It would be too strong to say that she felt rejection,” he said. But she felt “that he was distancing himself from her.”

As Dunham’s uncle Charles Payne takes pains to tell Scott, family history is recalled in fragments, reassembled and turned this way and that, distorted and reimagined, depending on the narrator. He offers examples, then looks at her evenly:

“All of this is just to tell you: Don’t trust memory.”

Better, instead, to follow the guidance of Stanley Ann Dunham Obama Soetoro, who always instructed her young research assistants, and her children, to emphasize “accuracy, rigor, patience, fairness, and not judging by appearances. ” ‘Don’t conclude before you understand,’ ” a friend from the Ford Foundation recalled her saying. ” ‘After you understand, don’t judge.’ ”

Ann Gerhart, an editor at The Washington Post, is the author of “The Perfect Wife: The Life and Choices of Laura Bush.”

(c) 2011, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.