NFL’s Handling of CTE Controversy Shows Compassionate Conservatism of Roger Goodell in Action

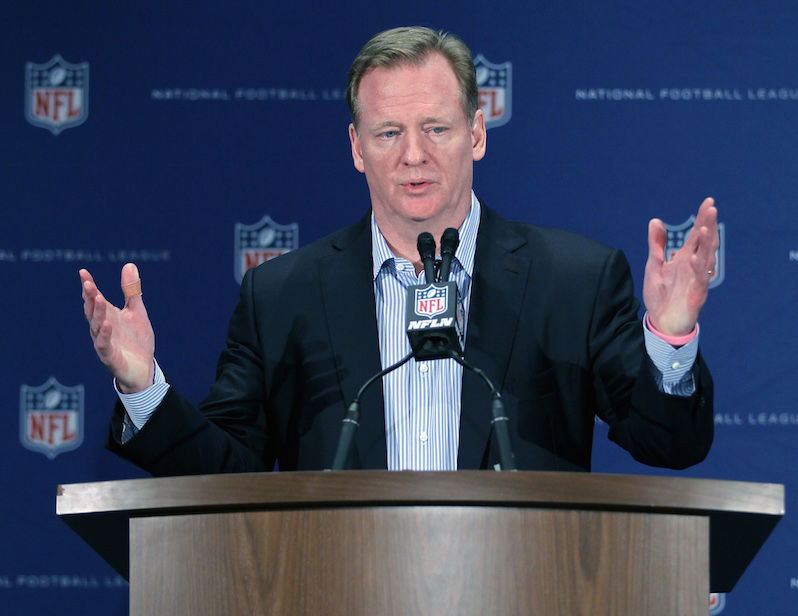

In determining the effect of concussions on the lives of football players, nobody lawyers up while making sincere protestations of loving the other side like the NFL commissioner. Roger Goodell has been the NFL commissioner since 2008. (Luis M. Alvarez / AP)

1

2

Roger Goodell has been the NFL commissioner since 2008. (Luis M. Alvarez / AP)

1

2

Roger Goodell has been the NFL commissioner since 2008. (Luis M. Alvarez / AP)

Is comparing the NFL’s handling of its health crisis to the tobacco industry a fair comparison?

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.