Mr. Magoo Vs. Daredevil: Are Blind ‘Superpowers’ Another Caricature?

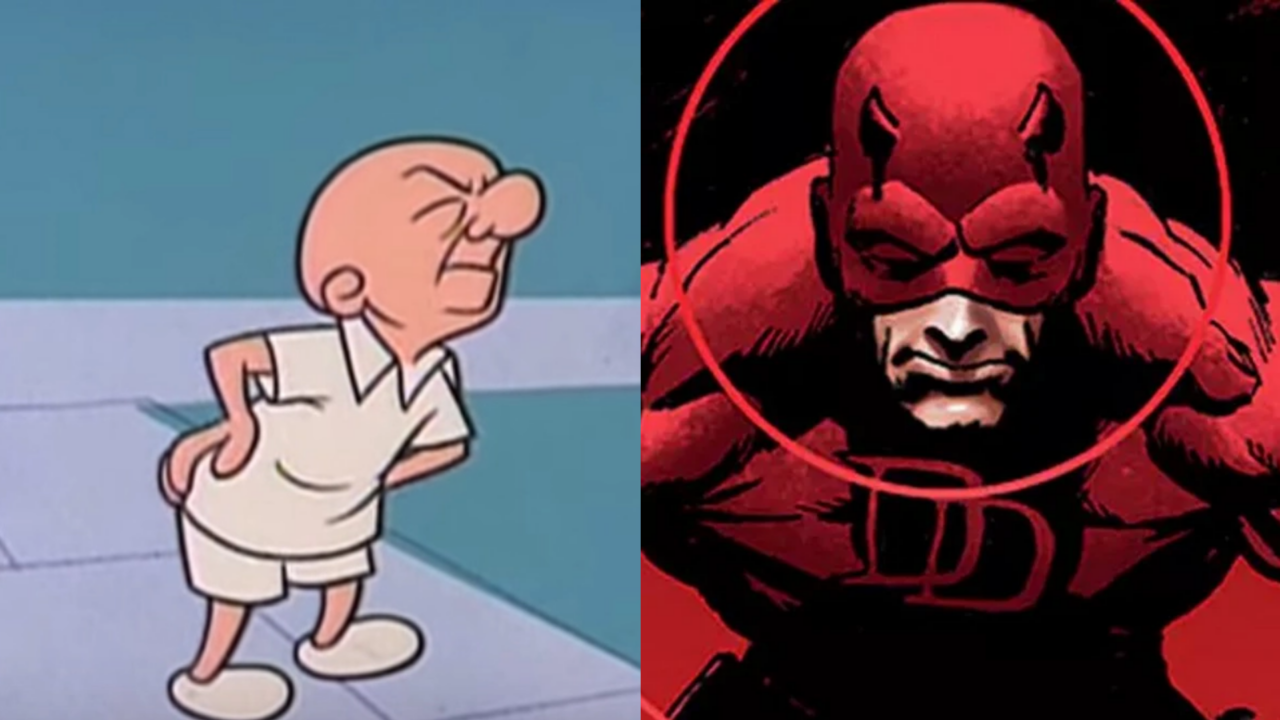

A medical screening program in India reinforces belief in blind "superpowers." What does the science say? Mr. Magoo (UPA animation) and Daredevil (Marvel Comics)

Mr. Magoo (UPA animation) and Daredevil (Marvel Comics)

In 2005, the German government instituted a national mammography screening program that required women seeking a scan to visit one of the specialized, state-sanctioned mammography facilities scattered around the country. Realizing the new program would take a big bite out of his private practice, Duisburg-based gynecologist Dr. Frank Hoffmann developed a workaround that wouldn’t violate the new regulations.

After setting up a nonprofit he called Discovering Hands, Hoffmann began training blind women to conduct breast exams. Graduates of the training program were certified as Medical Tactile Examiners, or M.T.E.s, and took jobs at area hospitals. Along with offering early breast cancer screenings to women who might not be able to travel to one of the state-run clinics, the program also provided blind women with a steady income. Then as now, the worldwide unemployment rate among the disabled wavered between 75% and 80%.

The reasoning behind the Discovering Hands program was simple. A blind woman’s sense of touch is so acute that, with proper training, it was assumed she would be able to detect breast lumps much smaller than anything a sighted doctor could find — possibly even smaller than anything picked up by a standard mammogram.

After trademarking the name and patenting the training technique, in 2009 Hoffmann began licensing Discovering Hands franchises in countries where mammograms are not easily accessible, such as Columbia, Mexico and India.

The growing program in India has received a good deal of press in recent months, often taking the form of inspiring stories about disabled people making themselves useful in the world.

“Being an M.T.E.,” one woman told The Guardian, “gives me the feeling that I have a unique quality to do something that only I can do as a disabled woman.”

“The reality is that blind superpowers are a myth.”

By way of transparency, I’m blind. A progressive genetic condition, retinitis pigmentosa, left me without sight about 25 years ago. During a recent checkup, my neurologist asked if I had someone help me when it came to taking my assorted medications.

“No,” I said. “All the pills are different shapes and sizes, and they’re all in differently shaped bottles. So, it’s not an issue.”

She paused for a moment. “Isn’t it amazing?” she said. “When you lose one of the senses, all the others become so much more acute.”

It was disheartening to hear this coming from a neurologist, but it was hardly the first time a medical professional had mistaken my ability to perform simple tasks as evidence of uncanny magical abilities. These abilities are at the heart of the Discovering Hands story. “If you’re in an exam room and a blind woman comes in, you might think that’s cool because she’s magic,” says Andy Slater, a blind audio engineer, musician and disability rights activist.

But the exchange with my doctor illustrates the way public perception of the blind cuts two ways. One extreme holds that we’re pitiable, helpless incompetents who need help dressing or taking our daily meds. The other, far more popular extreme, maintains that the loss of sight hones our other senses to superhuman levels and, on occasion, allows us to see the future.

The belief that blindness, unlike any other disability, is by nature accompanied by special powers can be traced back thousands of years. In Greek mythology, Zeus felt bad about blinding Tiresias, so gave him the power of second sight. In early 20th century mysteries, blind pencil salesmen were invaluable police informants, capable of describing a suspect’s height, weight, attire, social status and occupation after the briefest of encounters. More recently, the blind comic book hero Daredevil is a master martial artist with super hearing, touch and agility, able to dodge speeding bullets. In “Scent of a Woman,” Al Pacino’s blind character can dance the tango in a crowded restaurant without bumbling into a single table.

“It is a question I get a lot from well-meaning sighted people,” says Andrew Leland, whose new book, “The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight,” was released earlier this month. “‘Has your hearing improved since your vision declined?’ ‘Do you have heightened senses?’” He cites the example of being asked if he could tell the difference between 500 and 450 thread-count shirts by touch alone. “The reality is that blind superpowers are a myth,” he says.

In The Guardian profile of the Discovering Hands program, one passage in particular caught my eye: “Maurya, who has no vision in one eye and can only see shapes from the other, says her impairment heightens her tactile abilities — and science supports her.”

Does it? Is there any solid evidence the blind really are blessed with miraculous hearing, touch and smell?

“The blind person doesn’t have better hearing, but they are usually paying closer attention to the sonic environment.”

The New York-based ophthalmologist Dr. Jeanne Rosenthal pointed me to two major studies conducted in 2017 and 2019. Both concluded that subjects who were born blind or went blind before the age of three experienced neuroplastic changes over time; that is, the brain rewired itself to focus on the remaining senses, resulting in measurably heightened auditory and tactile abilities. In a vast majority of cases, however, blind people are not born blind, but experience the gradual deterioration of their sight over a period of years. In those cases, the results were far less impressive.

“It probably varies with the individual,” Rosenthal says. “I also think better senses can be developed, and that’s probably what happens. That’s why people feel they don’t have the finger sensitivity to learn Braille, but do when they need it. When you need to rely on your other senses, you become more aware of them.”

Leland agrees.

“In this way superpowers are nothing more than specialized skills, tools that most sighted people have no reason or occasion to use,” he says. “The blind person doesn’t have better hearing, but they are usually paying closer attention to the sonic environment. They’re likelier to hear the cab pull up before everyone else, only because everyone else is too busy looking at their phones.”

This is a matter of what phenomenologists call “intentionality”: closely analyzing and interpreting the sensory information that’s coming in through your eyes, ears, nose and fingertips to better understand the world. When you remove the distraction of vision from the equation, you pay much more direct attention to the remaining senses.

Writer and performer Dr. M. Leona Godin doesn’t disagree with Leland and Rosenthal, but pushes the idea one step further. “A big problem with a lot of these studies is that training is left out of the question,” she says. “It’s like blind people are dropped into the world and either become ‘super-blind,’ or not. Never mind the training that goes into being good at anything. Good training when our brains are still soft and squishy is key. I and a lot of kids who were clearly losing the ability to read at a young age were not given Braille training, so our tactile abilities didn’t get the boost that totally blind kids got.”

Godin, author of “Their Plant Eyes: A Personal and Cultural History of Blindness” and editor of the olfactory-centric lit journal Aromatica Poetica, consents that focused attention is also a major factor. “It’s easy to demonstrate,” she says. “Stick a sighted person in a cocktail party or a crowded train, ask them to close their eyes, et voila! I guarantee they will hear things they hadn’t been privy to a moment before.”

It’s little surprise, then, that when it came to the early detection of breast cancer, a 2019 study revealed the blind M.T.E.s involved with the Discovering Hands program had an accuracy rate on a par with sighted doctors. No worse, but not markedly better, either. The data blew a hole in the program’s basic premise, but to members of the blind community, that’s not the most important issue.

“A big problem with a lot of these studies is that training is left out of the question.”

“In a world where most people can’t fathom how a blind person can do any job,” Leland says, “it’s hard for me to criticize an initiative that plays to a blind person’s strengths, even if some mystical fairy dust gets sprinkled onto the proceedings along the way.”

As Andy Slater put it, “Even if it’s a grift, it’s giving blind women jobs, and this is a good thing.”

Of course, for all the studies and explications and the demystification on the part of the blind themselves, the myth of blind superpowers isn’t going away anytime soon. After thousands of years it’s been hardwired into the (sighted) collective consciousness, with movies, TV and comic books providing regular reinforcement.

Given the blind will likely never fully escape the stereotype, there is (on occasion, anyway) the temptation to play it up.

If the questioner is genuinely curious and time affords itself, Godin says she’s happy to explain perceptual psychology, neuroplasticity and the role of attention. “If it’s some random person on the street,” she admits, “then heck yeah, I’m superpowered. And I’ve been known to say onstage that I’ve got ‘a touch of clairvoyance, as do all my people.’”

“I do that all the time, man,” Slater says. Being magic is a big help in his audio work. “‘Hey, it doesn’t matter that I was in metal bands. ‘I’m blind, so I can hear this better than you.’ When I worked at Best Buy, that’s how I could sell people $200 headphones. But if I try to pull that with disabled friends, they give me no end of shit for it.”

After spending too much of my youth in punk clubs, and after four decades of chain-smoking, I’m in no position to make any bold claims about my supersensitive hearing and smell. The truth is, I’m much closer to Mr. Magoo in temperament and ability than any Marvel super hero. But if the manager of the liquor store I frequent wants to believe I have a little Daredevil in me, all because I can find what I want on the shelves by touch alone, and then give him the correct change, well, there are worse things.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.