Morocco’s War Against the Sahrawi

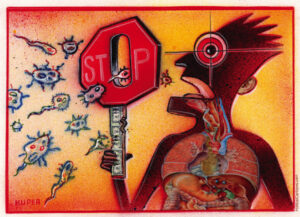

In the Phosphorus-rich Western Sahara, the government in Rabat used the pandemic as cover for a bloody political crackdown. The Moroccan flag is ubiquitous throughout Laayoune, a visual reminder of Morocco's authoritarian grip. Photo by Kang-Chun Cheng

The Moroccan flag is ubiquitous throughout Laayoune, a visual reminder of Morocco's authoritarian grip. Photo by Kang-Chun Cheng

LAAYOUNE, Western Sahara — One day in November 2020, Sultana Khaya was driving to her home in the town of Boujdour when she was detained at a Moroccan military checkpoint. It seemed as if the officers were waiting for her. They dragged her to a police station where she claims officers sexually assaulted her, then placed her under house arrest along with her sister, Luara, and their elderly mother.

Khaya is president of the Sahrawi Association for the Defense of Human Rights and an activist who fights for independence for Western Sahara, a land about the size of Colorado, 80% of which has been occupied by Morocco since 1975, the other 20% of which is controlled by the Polisario Front, a nationalist movement working to liberate the territory from Morocco. The United Nations calls Western Sahara a Non-Self-Governing Territory lacking any administrative power.

Tensions there have been heating up since 2020, when a 29-year-long ceasefire between Morocco and the Polisario Front collapsed and fighting resumed. Independence activists seized the moment to organize protests and resistance efforts; Morocco’s crackdown was swift and furious.

These events occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Morocco weaponized the health crisis for political ends, placing activists under house arrest under the auspices of distancing measures, and shutting down independent newspapers on the unsupportable basis that people touching their pages might spread the virus.

“When COVID-19 started, all the human rights defenders were held prisoners in their homes.”

During her confinement, Khaya says, she was repeatedly sexually assaulted by Moroccan security forces. When she contracted COVID-19 in 2021, with fevers running as high as 104 degrees Fahrenheit, she was effectively denied medical treatment —including basic medicine such as paracetamol — on account of her house arrest. “When it comes to the health sector in the occupied territories, there is basically nothing, no access,” she said. Khaya says she has never been presented with any criminal charges or a court order authorizing what became a 482-day detention under the auspices of Morocco’s COVID-19 lockdown.

“When COVID-19 started, all the human rights defenders were held prisoners in their homes,” Khaya said over an encrypted call. “These political actions just confirm to us that we are victims of a conspiracy between Morocco and its allies. As Sahrawis, we know we are targeted.”

Governments across the Middle East and the globe, from Venezuela and Turkey to Kenya and Cameroon, have used the pandemic as an excuse to violate human rights, according to Amnesty International. But Morocco’s crackdown on Sahrawi independence activists has intensified since the pandemic, too. Since November 2020, Amnesty International has documented nearly two dozen cases of torture, home raids, house arrests, arrests, detentions and harassment — including against journalists, human rights defenders and minors. “The Moroccan authorities have intensified their spate of violations against pro-independence Sahrawi activists … to silence or punish them for their peaceful activism,” the group wrote.

A joint statement issued by U.N. special rapporteurs in January 2021 denounced abuses against eight human rights defenders in Western Sahara, citing allegations of violations including violence, death threats, physical surveillance, arbitrary detention, ill-treatment in detention and torture at the hands of Moroccan security forces. Today, as much of the world’s attention fixes on Israel’s war on Palestine, some Sahrawis are pleading for solidarity with the plight of a different occupation, one that the world has largely forgotten.

Morocco is Africa’s third-largest tourist destination, known for colorful medinas full of spices and rugs, a rich architectural heritage, surfing-ready beaches and imposing mountain ranges. At about half a million square kilometers, Morocco is just slightly larger than California. It is also home to a stretch of the Sahara Desert — which takes up about 40% of the landmass — that is the battleground of the Sahrawis’ 50-year struggle.

The current conflict dates to 1975, when Spain relinquished its colonial rule of Morocco’s Western Sahara region. Today, Western Sahara is home to fewer than 600,000 souls, or roughly 10% of the population of Wisconsin. Western Sahara holds an average of just six people per square mile of desert — six times the population density of the Sahara as a whole — most of whom live in towns, cities or refugee camps. Starting in the 1970s, the Kingdom of Morocco fought for territorial claims to the land. Morocco’s main interest in the region was its rich reserves of phosphorus, a key global component of agricultural fertilizers. Today Morocco controls 70% of the world’s phosphate-rock reserves.

The current conflict dates to 1975, when Spain relinquished its colonial rule of Morocco’s Western Sahara region.

In the 1970s, Morocco encouraged tens of thousands of settlers to build homes and sent soldiers to root out the young Polisario Front, founded in 1973 as an independence movement against the Spanish. In 1980, Morocco began constructing a now 1,700-mile long wall, the Berm, to seal off the territory it controlled from the areas controlled by the Polisario Front. Land mines were planted in and around the Berm to deter Polisario rebels from attempting to cross. The grueling war finally ended with a 1991 ceasefire brokered by the U.N. and African Union.

But the ceasefire did not end disputes over the territories’ borders and a proposed census to determine who can vote in an independence referendum. In the decades since, Morocco has repeatedly rejected a U.N. peace plan and refused to allow the vote to go ahead. As a result, much of Western Sahara remains under de-facto annexation by Morocco — a violation of international law. Morocco keeps the territory under strict surveillance and stamps out peaceful advocacy for liberation with physical force. In Morocco, even the term “Western Sahara” is highly taboo. Moroccans use euphemisms like “southern Morocco” instead.

Only a small portion of the phosphate riches Morocco controls today are actually in Western Sahara, explains Erik Hagen, director of the advocacy group Norwegian Support Committee for Western Sahara, “but from a Sahrawi perspective, it’s massive. This could be a mine that could build their future welfare state. Polisario has been very vocal about Morocco’s plunder of Sahara’s phosphates. The occupation is costly — attracting settlers [requires] subsidies, infrastructure.” Western Sahara’s phosphate, says Hagen, “helps to pay that bill.”

In 2017, Sahrawi and international pressure on companies to stop buying pilfered phosphate from Western Sahara began to see results. Seizures of ships by the South African government carrying the commodity stopped shipments around the Cape of Good Hope and through the Panama Canal. But shipments around the Cape have resumed since rebels in Yemen began attacking cargo ships in the Red Sea in retaliation for Israel’s war on Gaza. Once Morocco completes a new port on the Saharan coast that will allow it to export processed phosphate, Hagen says, “the Moroccans may be able to attract foreign companies and governments into the plunder directly” because “there is only a small number of factories in the world that have the ability to transform unprocessed phosphate rock into fertilizers.”

Much of Western Sahara remains under de-facto annexation by Morocco — a violation of international law.

In 2010, Morocco arrested 65-year-old Sahrawi activist Sid’Ahmed Lemjaid, who has long advocated against Morocco’s sale of phosphates from Western Sahara, after he visited a Sahrawi refugee camp to interview its residents. He was later sentenced to life in prison for allegedly attempting to murder Moroccan officials — crimes to which Morocco’s government claims he confessed. (Lemjaid says he was tortured). In 2023, the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention called for the immediate release of Lemjaid and 17 other Sahrawi political prisoners’ who are in jail or under house arrest.

Among them is 39-year-old Mahfouda Lefkir, whose home Moroccan security forces raided in May 2023. She was charged with obstructing justice and detained for days in solitary confinement.

“I was thrown into a very small and foul-smelling cell with humidity, darkness and cold, without any blankets and with insects,” Lefkir told human rights investigators. “Then I was taken to an interrogation room where they undressed me completely and left me naked. Twice they interrogated me about my relationship with the Polisario Front, my political activities, my involvement in protest gatherings.”

She says Morocco has kept her under strict house arrest ever since.

Morocco scores just above Pakistan, and well below El Salvador, in rankings of “global freedom” compiled by Freedom House, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group. The COVID-19 crisis provided the cover for its government to step up its repression of Sahrawi activists like Khaya and Lefkir.

By the data, Morocco, a lower-middle-income country, should have been at a disadvantage in fighting the spread of COVID-19. Morocco ranks 108 out of 195 countries, and 11th in Africa, on the Global Health Security Index. Still, the government performed admirably at acquiring vaccines and distributing them — in Morocco: the government claims more than two-thirds of Moroccans have received a vaccine, just below the global average. (This success may not encompass Western Sahara: Morocco does not keep data on the territory, making it a blank spot on the World Health Organization’s map of COVID-19 cases, deaths and vaccines.)

Human rights activists say any successes in Morocco must be weighed against the authorities’ use of the pandemic as an excuse to muzzle its people, as the government was strict about enforcing distancing measures when they went hand-in-hand with repressing independence activists.

Human rights activists say any successes in Morocco must be weighed against the authorities’ use of the pandemic as an excuse to muzzle its people.

For its part, Morocco has denied that it kept the activist Sultana Khaya under house arrest at all. But the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention determined that the Khayas’ house arrest lacked any legal basis, reporting that they were “deprived of their liberty on discriminatory grounds, because of their status as Sahrawis and their political opinions in favor of the self-determination of Western Sahara.” The case has also been acknowledged by Human Rights Watch and the U.S. Department of State.

A year into Khaya’s house arrest, on Nov. 8, 2021, Moroccan security agents in plainclothes again raided her home. She said one officer injected her right hip with an unknown substance. Another said to her, “Now you will be sick. You will be unable to protest.” She said the injection made her dizzy, caused her to vomit, and that it caused her to lose feeling and movement in her right arm and leg. Seven months later, in late May 2022, she decided to try and escape house arrest and go into exile. Security officers trailed her from her home in Boujdour to Laayoune, the territory’s largest city and unofficial capital. But when she went to board a flight to Spain’s Canary Islands, off the Saharan coast, authorities did not prevent her from leaving.

Upon her arrival in Spain, Khaya received medical and psychological treatment for the trauma she suffered during her 18-month-long house arrest. It was there that she received her first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Khaya isn’t the only Sahrawi activist to allege Morocco denied health care to dissidents who came down with the disease. Among them is the family of Mbarek Daoudi, a lifelong dissident who was imprisoned for revealing to foreign journalists the gravesite of a family he watched Moroccan soldiers’ massacre in 1976.

In late August, 2021, Daoudi was at home in Guelmim when his health took a sudden turn. He was suffering from shortness of breath and tested positive for COVID-19 at a hospital in Laayoune. He was admitted to the military hospital in Klimim, where, his family alleges, he was denied treatment. He received oxygen, but only for a day due to citywide medical supply shortages.

Without oxygen support, Daoudi’s health deteriorated again, which he communicated to his son Hassan over a call. “My mother, my brothers Taha and Ibrahim went and protested in front of the hospital,” demanding better treatment for the activist, said Hassan. “It actually worked. The hospital director was forced to give him oxygen.”

A week later, the doctor in charge informed Daoudi’s family that he had recovered but would needed an oxygen machine upon discharge — the doctor provided a medical certificate to purchase a 5-liter generator, which his sons managed to buy for 2,800 euros despite the scarcity of such medical equipment in Laayoune. Just two days after his discharge, in September 2021, Daoudi passed away at age 65. His family and friends accuse the military hospital — and by extension, Morocco’s government — of failing to properly treat him. Hassan believes that his father’s untimely death was “all a government scheme,” a point of view shared with other Daoudi supporters. (Truthdig was unable to reach Morocco’s military for comment as it does not maintain a functioning website and its Twitter account does not allow direct messages.)

“The general opinion persists in the occupied territories that COVID is being used as a weapon against the Saharawi civilian population,” wrote the family’s attorney, Cristina Martínez Benítez de Lugo. “The Saharawis never trust Moroccan hospitals. Entering a hospital with COVID is entering to die.”

If Morocco’s authorities view political opponents like Khaya and Daoudi as threats, the press has fallen in Morocco’s crosshairs, too. Morocco ranks 135 out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ press freedom index, which lists it as “not free,” placing it among autocratic countries like Zimbabwe and Rwanda, as well as neighboring Algeria. (One study found a strong correlation between countries’ press freedom and their manipulation of COVID-19 data.)

“The Saharawis never trust Moroccan hospitals. Entering a hospital with COVID is entering to die.”

Last year, Morocco denied health care to imprisoned journalist Omar Radi, whom authorities arrested six years earlier on baseless charges of undermining state security and sexual assault after he exposed a corruption scandal in which top Moroccan officials were stealing land.

The status of the Western Sahara is one of “many subjects that have been implicitly off limits for Morocco’s journalists in recent years,” according to Reporters Without Borders. “Recent additions to the list include the security services, the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and the crackdown on street protests.”

The government’s actions seem to have affected Sahrawis’ attitudes toward protecting themselves from the COVID-19 virus. Many whom Truthdig spoke to expressed skepticism about vaccines. “I’m afraid that if I get the vaccine, I might die,” said a Sahrawi truck driver, Mohammed, in Laayoune. Here, “there’s a lot of people that don’t get the vaccine.”

“It’s because it comes from the government that people don’t agree,” said Noufan, an unvaccinated college student who also expressed doubts about the safety and efficacy of scientifically-proven COVID-19 vaccines. “Some people even cheat and buy a fake certificate,” a classmate named Yahdiha chimed in. “Then there are the objectors who have an opinion against the government — not because they’re Sahrawi, but they’re against government politicians” of any sort.

“Culture and religion play a role here,” a professor and translator who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons told Truthdig. But the primary driver for vaccine hesitancy is that Sahrawis “don’t trust the government and [think that] everything offered by authority will affect them badly.”

As a small territory with little standing on the international stage, Western Sahara is easily buffeted by geopolitical shifts. After losing the 2020 election, following decades of U.S. support for Sahrawi’s right to vote for independence, the Trump administration reversed course and endorsed Morocco’s rule. The change was announced in tandem with Morocco’s normalization of relations with Israel.

“The United States recognizes Moroccan sovereignty over the entire Western Sahara territory,” declared the U.S. Embassy in Morocco’s capital, Rabat. “To facilitate progress toward this aim, the United States will encourage economic and social development with Morocco, including in the Western Sahara territory.” Spain soon followed America’s lead, endorsing Morocco’s formal occupation.

Thus emboldened, King Mohammed VI delivered a speech on Nov. 6, 2021, asserting, “Morocco is not negotiating over its Sahara” since “the Moroccanness of the Sahara is an immutable and indisputable fact” while paying lip service to Morocco’s “commitment to a peaceful solution” to the fate of Western Sahara.

“Morocco relies on the same tools and methods as Israel in suppressing the Palestinians, occupying them, displacing them from their land, robbing them of their wealth and controlling them.”

In October 2022, U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres expressed his concern for “significant deterioration of the situation in Western Sahara.” He attributed low-intensity hostilities between Morocco and the Polisario Front to both regional tensions and COVID-19, mentioning drone strikes by the Royal Moroccan Army that have resulted in civilian casualties. “Provocations confirm Morocco’s aim to sow and maintain tensions in the region,” he wrote.

That same month, another longtime Sahrawi activist, Ali Salem Tamek, was allegedly assaulted by security forces in Laayoune. Tamek routinely documents human rights issues as a founding member of the Western Sahara branch of the Forum for Truth and Justice and vice president of the Sahrawi Collective of Human Rights Defenders.

One year later, hundreds of thousands of people began taking to the streets to protest Israel’s military assault and invasion of Gaza.

“There is a total similarity between what is happening in the Western Sahara and Palestine,” Mohammed Elbaikam, a Sahrawi activist, told Middle East Eye. “Morocco relies on the same tools and methods as Israel in suppressing the Palestinians, occupying them, displacing them from their land, robbing them of their wealth and controlling them.”

In November, thousands of Moroccan protesters gathered in Casablanca to protest Morocco’s newfound support for Israel. But whether Moroccans will take the political risk of extending their solidarity with occupied Palestinians to occupied Sahrawis, remains to be seen.

Kang-Chun Cheng and a translator in Laayoune who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, contributed reporting.

Jacob Kushner’s forthcoming book, Look Away: A True Story of Murders, Bombings, and a Far-Right Campaign to Rid Germany of Immigrants, will be published in May 2024 by Grand Central (Hachette).

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.