Make Your Vote Count for Socialism

Stewart Alexander believes fair elections are worth a fair fight and he’s asking for your vote The Occupy Wall Street movement encouraged a more honest discussion of class and capitalism in this country, but Alexander is not simply a critic of big banks and high finance .

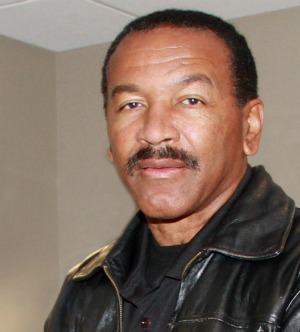

Stewart Alexander believes fair elections are worth a fair fight and he’s asking for your vote. The Occupy Wall Street movement encouraged a more honest discussion of class and capitalism in this country, but Alexander is not simply a critic of big banks and high finance. He is a democratic socialist, an African-American community activist and the presidential candidate of the Socialist Party in 2012.

Alexander believes the candidate of “hope and change” is a defender of the status quo and of corporate rule. In his words:

“The phrase that came to mind immediately upon hearing President Barack Obama’s State of the Union speech is ‘too little, too late.’ After spending the last few years coddling the banks and the richest 1 percent, Obama has the nerve to now call for ‘economic fairness.’ To him, this means tweaking payroll taxes and making a rhetorical call to reverse the Bush tax cuts for the rich. For working people in America, real fairness means the right to a job, a guarantee of health care for all and an end to the military-industrial complex. Obama won’t deliver this. That’s why I am running for president against him.”

The boom-and-bust cycles of capitalism require a semblance of representative government, even though Congress has become the front office of the corporate state. Even the most “progressive” reforms of the tax code now proposed by career politicians remain a form of institutionalized robbery of the working and middle classes.

“This is why,” Alexander says, “we propose creating a progressive tax structure where the rich pay far more than the average working person. In a democratic socialist society neither Obama nor Romney would be allowed to pay an effective tax rate of 26 percent and 17 percent, respectively. Corporate taxation, financial gains taxes and personal income taxes will be modernized — all loopholes will be closed and the rich will pay a steep tax on their income. This is what economic fairness looks like to a socialist.”

Is a radical revision of the tax code the whole program of democratic socialism? No, but it is certainly one reform consistent with social democracy in the realm of the economy. Alexander is not simply a “left-wing Keynesian” reformer. After all, economist Paul Krugman plays that part admirably in the Op-Ed pages of The New York Times. Krugman repeatedly insists that the Obama administration must ramp up a “stimulus package” that might actually stimulate, rather than stifle, the economy. But Krugman would need genuine social democrats in the White House to listen to his advice, whereas Obama has filled his inner circle with Wall Street aristocrats such as Timothy Geithner. Alexander’s reform of the tax code has a much deeper foundation in workplace democracy, and in working class solidarity across national borders.

Alexander has also been a strong critic of Obama’s “continuation of the Bush era security state policies.” He has the same moral fire and political clarity as Eugene Debs, a Socialist presidential candidate who won 6 percent of the national vote in 1912, and gained more than 900,000 votes in 1920 even when he was behind bars at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. Debs called for working class unity against war and imperialism, and he paid a high price. We now live under a regime of escalating state surveillance and police repression, and Alexander’s class conscious policy of peacemaking will not earn him a Nobel Peace Prize:

“Obama’s approval of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) annihilates centuries of civil rights protections,” Alexander writes. “The president now has the right to indefinitely jail any citizen in America without having to work within the protections of habeas corpus. Added to the NDAA is the fact that, as I write this, Bradley Manning is rotting in a jail cell. Manning is Obama’s prisoner — a moral testament to the president’s commitment to continue the job of restricting civil liberties.”

Alexander was born in Newport News, Va., in 1951. He was one of eight children of Stewart Alexander, a brick mason and minister, and Ann E. McClenney, a nurse and housewife. In 1953, the family moved to the community of Watts in Los Angeles. Bricklaying and masonry jobs were scarcer in Los Angeles, and the family endured some hard times. At the age of 16, Alexander worked nights with his father cleaning airport terminals.

In the late ’60s, Alexander attended George Washington High School in Los Angeles County. Though integration of public schools had become public policy, the foundation of the educational system fractured along lines of race and class. By the time Alexander graduated from high school in 1970, the school had fewer than 50 white students. This was part of a wider social pattern that became known as “white flight.”

In December 1970, Alexander joined the Air Force and trained as a transportation and cargo specialist. Later he attended college full time at a Cal State University campus. One professor actively discouraged his studies, and when he quit college he began working 40-plus hours a week as a stocking clerk. During this time he married his first wife, Freda Alexander, and they had one son.

After working as a licensed general contractor and with Lockheed Aircraft in Burbank, Calif., he returned to Los Angeles and applied for a job as a warehouseman and forklift driver. Though his military experience made him well qualified for the job, the warehouse manager refused to interview him. Only the threat of a lawsuit (including filing a complaint to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) gained him the interview and the job.

The manager later confessed to Alexander that it was his policy to hire only blacks who were “twice as good” as whites on the job. Having fought to get that job, being “twice as good” also meant that Alexander (one of only two African-Americans among 200 employees) had to work more than twice as hard.

During this time Alexander began working with civic and community groups, including the NAACP. He later traveled to Tampa, Fla., working as a grocery clerk and as an organizer with the Florida Consumer Action Network (FCAN). In 1986, Ralph Nader was the guest speaker at the state convention of FCAN, and Alexander joined him in political discussions during the event. Alexander also worked briefly with an affiliate organization, the Long Island Citizens Campaign. Both groups were formed to protect the environment and the health and safety of consumers.

In 1986, Alexander moved back to Los Angeles and immediately got involved with local organizations. For more than three years he hosted a weekly radio talk show on KTYM-AM in Inglewood, discussing crime, gangs, drugs and redevelopment issues. Working with Delores Daniels and other community activists, Alexander brought public attention to local communities that were losing billions of tax increment dollars, while redevelopment tax revenues were funneled to well-connected capitalists and to big projects in downtown Los Angeles.

In 1988, Alexander moderated a public forum in Los Angeles that gave more than 200 community groups and activists the opportunity to meet with elected officials and to address redevelopment issues. At the same time, Alexander launched a campaign to become mayor of Los Angeles and knocked on more than 14,000 doors to get the minimum 1,000 signatures needed to qualify for the citywide ballot. Alexander’s campaign dealt with reducing crime, creating jobs for communities of color and the economic redevelopment of Los Angeles. The social and economic divisions Alexander had warned about for years finally erupted in riots and arson on April 29, 1992.

Alexander began looking and thinking beyond an electoral system dominated by two big corporate parties. He was briefly inspired by the campaign of Ross Perot, and in 1991 he attended a rally in Orange County, Calif., where Perot spoke to a crowd of about 5,000. But his political life then grew less active for several years. In the life of individuals and in the history of nations, there are times when still waters run deep. In 1998, Alexander met Kevin Akin of the Peace and Freedom Party, and Alexander’s class conscious politics became explicitly socialist. In 2005, Alexander ran as the Peace and Freedom Party’s candidate for lieutenant governor of California. Shortly after, Alexander was elected to the state executive committee of the Peace and Freedom Party.

Alexander has worked with the Socialist Party since 2007, and was its vice presidential nominee in 2008. At the National Convention for the Socialist Party USA in October 2011, Alexander was nominated for president of the United States. Alejandro “Alex” Mendoza, his vice presidential running mate, was born in Riverside, Calif., to parents who emigrated from Mexico. Mendoza served in the Marine Corps for four years and now lives in Texas where he owns a sustainable lawn care business and is pursuing a master’s degree in geosciences at the University of Texas.

Stewart Alexander is happily married to his second wife, Vicki Alexander. They have four children and six grandchildren. A resident of Murrieta, Calif., a community that leans quite far to the right, Alexander is openly committed to the democratic left. The program of the Socialist Party of the United States is both class conscious and civil libertarian, and Alexander will give American voters a chance to truly make our votes count for democracy and socialism.

I am a member of both the Socialist and Green parties of the United States, and I have met Alexander several times at meetings of the Los Angeles chapter of the Socialist Party. That is considerably more disclosure than most readers get from the regular columnists in major newspapers, or than most viewers get from the expensively groomed anchors of TV broadcast networks. The price of journalistic “access” to many career politicians is quite simply the professional prostitution of journalists. For this Truthdig article, I addressed five questions to Alexander.

Scott Tucker: As many jobs have been shipped offshore in the corporate chase for the lowest wages, the percentage of United States workers who belong to labor unions has fallen to roughly 12 percent. What are your views about rebuilding a base of manufacturing jobs in this country, beyond the sector of military industries?

Stewart Alexander: I am running this campaign in order to offer a democratic socialist alternative to American voters. What this means in real terms is that I believe that we can make real on the great possibilities offered by this society. For instance, I believe that we can rebuild the manufacturing sector in the United States and, even better, I believe that it is possible to do so in a democratic way that allows us to build a society based on solidarity and justice. Yet, since the 1970s, Democrats and Republicans have been firmly committed to the plans of their benefactors in the corporate world who have sought to destroy the manufacturing sector and ship production sites overseas.

This plan worked quite well for the 1 percent in society. Manufacturing overseas allowed them to avoid the environmental, civil rights and labor laws that have been built up by social movements in the United States. Capital restored its profitability by globalizing itself. However, the production sites and communities it left behind, especially in the Rust Belt of the U.S., have now been reduced to Third World level standards with deep unemployment, decaying infrastructure and rampant drug use.

One of the reasons that the Alexander/Mendoza 2012 campaign exists is to say that another way is possible. We believe in the creation of an independent worker owned and operated cooperative sector that can be used to rebuild the manufacturing capacity of the United States. Public funds should be used to initiate this kind of project, instead of being poured into the financial sector through bank bailouts or into the expansion of the prison-industrial complex.

A vibrant cooperative network means that Americans will no longer have to be held hostage by multinational corporations. Democratically run cooperatives are rooted in local communities — they depend on local people to be their customers, they are supplied by other local cooperatives and they are not beholden to CEOs or boards of directors. Such enterprises also have a built-in incentive to care for the environment and enforce workers’ rights since the workers are owners, and they likely live in the same community they work in.

We think that an independent democratically run cooperative sector is a viable alternative to both multinational capitalism and the military-industrial complex. This is at the heart of our campaign. Tucker: The Socialist Party has a strong tradition of commitment to democracy, both within the labor movement and within the realm of electoral politics. But the legal and corporate obstacles have grown greater with the Citizens United decision of the Supreme Court and anti-democratic “reforms” such as Prop. 14 in California. In every big election the public is told, make your vote count. Yet in reality, many of our votes are discounted. How do we make our votes count at the state and federal levels especially? What reforms are necessary to challenge corporate politics and make electoral politics more democratic?

Alexander: As far as electoral reforms that are necessary to create a democracy in this country, we can divide them into two — first, those that need to be enacted immediately, and second, the longer term restructuring we would like to see. Obviously, both Citizens United and Prop. 14 need to be repealed. Consider Citizens United a kind of high point of neoliberalism — corporations as people capable of openly operating in the electoral finance arena without restraint. If the existence of the Occupy movement is any indication, neoliberalism’s life span might be in the process of being dramatically shortened by grass roots resistance. And this is the best way to think about overturning such undemocratic decisions — not primarily through a legal strategy, but through a democratic revolution from below.

Long term, we might learn some lessons from Latin America. In places like Venezuela and Bolivia, left-wing electoral parties were able to break through two party deadlocked systems. They did so by rooting themselves inside the struggles of poor and working class people. This is one lesson for the American left. However, what they have as yet failed to do is to transform the electoral system from one in which they are one of two parties into a pluralist political system where multiple views are represented.

This is why, in the longer term, we want to fight for electoral reforms such as public financing of elections, proportional representation and a uniform open ballot access law. Even more importantly, we should, wherever possible, seek to encourage direct democracy through more radically democratic reforms such as participatory budgeting which will allow people to have a real say in how public money is spent. The current electoral system — from local to the federal levels — is rigged to privilege moneyed interests. The Democrats and Republicans monopolize every aspect of it from the process of getting on the ballot to the debates. It is going to take more than an electoral campaign to make such changes happen. It might take a revolution.

Tucker: In a New Yorker article titled “The Caging of America,” Adam Gopnik wrote: “More than half of all black men without a high school diploma go to prison at some time in their lives. Mass incarceration on a scale almost unexampled in human history is a fundamental fact of our country today — perhaps the fundamental fact, as slavery was the fundamental fact of 1850. In truth, there are more black men in the grip of the criminal justice system — in prison, on probation or on parole — than were in slavery then. Overall, there are now more people in ‘correctional supervision’ in America — more than 6 million — than were in the Gulag Archipelago under Stalin at its height. That city of the confined and the controlled, Lockuptown, is now the second largest in the United States.” What are your thoughts and practical proposals?

Alexander: I think we should keep in mind that in the 1970s, the prison population in the United States had declined so rapidly that there were serious discussions about placing a moratorium on building prisons and only slightly more utopian proposals about ending incarceration entirely. Prison populations had declined about 1 percent a year since World War II and reached a low of 380,000 inmates in 1973. This, of course, was not to be, as politicians and policymakers took what academics call “the punitive turn” leading to mass incarceration strategies that disproportionately targeted people of color.

This too did not happen in isolation from other factors. The rise of neoliberal economics meant the end of the manufacturing sector, the destruction of social safety nets and the privatization of the education system. The prison-industrial complex is then used to warehouse and discipline those who have been left behind by an economic system that only considers the needs and interests of the 1 percent. It has been poor African-Americans who have suffered the brunt of this turn.

I believe that we need to enact policies emphasizing decriminalization while also creating spaces for the self-empowerment of poor and working class people. We must immediately end the destructive drug war by creating a legal justice system based on prevention, mediation, restitution and rehabilitation. That’s why, as president, I would support heavy investment in programs of restorative justice and other community based alternatives to incarceration. Where neoliberal politicians use force through criminalization to deal with social problems, a socialist would see the welfare state, rehabilitative services and economic empowerment as alternatives.

Tucker: Ever since the First World War, the Socialist Party has taken the position that a class conscious movement of workers must by necessity also be a movement working against militarism in culture and in the economy. We have barely begun accounting for the human, environmental and economic devastation of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The semi-secret drone war in Pakistan is not consistently reported by major news networks. We do not know the true cost of military bases scattered round the globe, as this has also become something of a state secret. And now we are on the verge of escalating hostilities with the regime in Iran. What are your immediate demands to prevent war? What are your long-range proposals for transforming the war economy into a commonwealth dedicated to peace?

Alexander: I want to be very clear about what my campaign’s position is on war and the military-industrial complex. I’ll start by saying that it is very easy to hold an anti-war position. Ron Paul has one. Plenty of Democrats and Republicans have them. But what makes a democratic socialist position so distinct, and, I would add, so important, is that we are not only anti-war but we are also anti-militarist. In other words, we seek to put a permanent end to the role of the U.S. military-industrial complex in our country and in our world.

You are correct to say that such a position is deeply rooted in the history of American Socialism. Comrades such as Eugene Debs went to jail in the early 20th century because they opposed World War I and the role of militarism in U.S. society. And, as John Nichols documented in a recent book, it was Socialist Party of America comrades who saved the First Amendment when militarists sought to restrict the right to free speech. Socialists have been present in every anti-war movement since — from the burning of draft cards in the Vietnam War to opposing the invasion of Iraq.

These same reasons hold true today. Military spending is a monumental waste of resources. Nearly 50 percent of the annual federal budget is consumed by paying for current and past wars. These funds could be better spent on dealing with serious social problems such as inadequate housing, the lack of health care and the dire need to rebuild our infrastructure.

Deeper than that, the death and destruction that the U.S. military has caused throughout the world — most recently in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan — has destroyed millions of potential bonds of global solidarity. We want to repair these bonds with socialist values of solidarity, compassion and justice.

Policy wise, we think this means at least three things immediately. First, we support the immediate removal of all U.S. troops from foreign countries and the ending of covert actions such as drone bombings. We also call for a 50 percent reduction in military spending and a redirection of those resources into social needs programs. Finally, we believe that we can develop a new global good will by closing all foreign military bases and the responsible elimination of all nuclear weapons.

I want to emphasize firmly that being anti-militarist is about more than just opposing the latest war. It is about seeing the American military for what it is — a force for global destruction and a serious threat to civil rights in the U.S.

Tucker: How did you find your way into the socialist movement? I’m not asking if you had a single big epiphany, but I am always interested in the background story of how people break away from “our two party system” and commit themselves to class conscious and independent politics. What experiences shaped your political views, and which social movements were decisive in your life?

Alexander: There really is no one single way to get involved in radical politics. For every active socialist I meet while campaigning, I hear a different story. Mine begins, funny enough, in the military. I saw the military-industrial complex from the inside and so did my running mate, Alex Mendoza, who was a Marine. My time in the Air Force led me to believe that the war in Vietnam was wrong — wrong for our country, morally wrong and politically wrong. This opened the door for me to ask some bigger-picture questions about how society works.

Perhaps, though, it started earlier. When I was a very young child I went with my father to hear Malcolm X speak when he visited a mosque in Watts. I cannot tell you that I remember anything that Malcolm said in particular, but I do vividly remember the presence that he commanded. He was a respected leader in that community, and I was impressed by how seriously he took that role. I hope to bring an equally serious approach to my presidential campaign since the problems we face as a society are just as serious.

As I grew older, I realized that there was political strength in numbers and I got involved first with the Peace and Freedom Party and later the Socialist Party USA. I liked the fact that both organizations place the interests of poor and working class people at the center of their political projects. Peace and Freedom provided me with the opportunity to run for statewide office, and I was quite happy to receive the nomination of the SP-USA convention to run a national campaign. I think that it is time to present a positive socialist alternative to the American people. I hope to play my role in doing so and ask you to vote Socialist in 2012!

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.