Lou Cannon on Ronald Reagan

The debate over our 40th president's role in ending the Cold War continues with the publication of James Mann's "The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan."

Former House Republican leader Newt Gingrich, chatting online with Politico, called President Barack Obama’s vision of a world free of nuclear weapons “a dangerous fantasy.” If so, it is a fantasy that Obama shares with Gingrich’s hero Ronald Reagan, who in the second term of his presidency negotiated successfully with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to reduce U.S. and Soviet nuclear arsenals and set the stage for the end of the Cold War.

Reagan was at once a fierce anti-communist and an advocate of abolishing nuclear weapons in direct negotiation with the Soviet Union. To national security establishments in both the United States and the Soviet Union, which depended on the threat of mutual nuclear annihilation to keep the arms race growing, Reagan’s views seemed contradictory. To Reagan—and eventually to Gorbachev, as well—these policies fit together and were aimed at securing a safer and more stable world.

In a previous book, “The Rise of the Vulcans,” journalist James Mann explored the significant influence of neoconservatives in the George W. Bush administration. His interesting conclusions came out of the reporting of the story, and a scary story it was. But in “The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War,” Mann begins with a dubious premise that he fails to sustain with research and reporting. The premise and the central contention of the book is that Reagan began his two-term presidency as an ardent Cold Warrior and—for reasons that are never precisely explained—changed his goals in midcourse and sought to bring this long conflict with the Soviet Union to a peaceful conclusion. Mann starts off by tearing down a straw man, which is his claim that there are only two essential explanations of Reagan and the Cold War. The first is the triumphalist view that Reagan single-handedly won the Cold War through a combination of “confrontation and pugnacity.” The second is that Reagan had nothing to do with the outcome—that he was “either lucky or irrelevant.” These indeed were once the competing caricatures of conservatives and liberals who were trying to explain history according to their ideologies, and there are still those on both sides of the barricades who indulge in such simplicities. But in the 20 years since the end of the Reagan presidency, the closing stages of the Cold War have been examined in nuance and complexity in a host of books that neither deify nor vilify Reagan (or Gorbachev, for that matter). These include books by academics such as Martin Anderson, Sean Wilencz and Philip Zelikow, journalists such as Don Oberdorfer and myself, former participants in the process such as George Shultz and Margaret Thatcher and many, many more. Two of the best—“Autopsy on an Empire” and “Reagan and Gorbachev: How the Cold War Ended”—were written by Jack F. Matlock Jr., the National Security Council expert on Soviet policy in the run-up to Reagan’s first summit meeting with Gorbachev and later, as Mann notes, a distinguished U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union. In Matlock’s account both Reagan and Gorbachev emerge as flawed but skilled negotiators who make mistakes but get the essentials right.

Mann also gives primacy to the Reagan-Gorbachev negotiations—they held four summits and a meeting with George H.W. Bush after he was elected president in 1988. But Mann’s premise that Reagan did not decide to end the Cold War until he’d been in office several years does not withstand close examination. As Mann sees it, there was an enormous contrast between Reagan’s first term, when he called the Soviet Union an “evil empire,” and his second, when he practiced diplomacy in negotiations with Gorbachev. In the first term Reagan built up U.S. military power and succeeded over the opposition of the nuclear-freeze movement in deploying U.S. intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Germany to counter Soviet missile deployments in Eastern Europe. “It seems likely … that Reagan’s opposition to nuclear weapons crystallized during these early years in the White House,” Mann writes. “Once he became president, Reagan was gradually obliged to confront the reality of what nuclear war would mean, and to recognize the necessity of split-second judgment and the possibility of error.”

Although having the power to push a button and wipe out civilization would doubtless concentrate the mind of anyone, Reagan had long worried about accidental nuclear war and opposed as immoral the doctrine of “mutual assured destruction,” or MAD, the premise of deterrence in the nuclear age. He expressed his fears in a dramatic speech to the Republican National Convention in 1976, just after he had lost the presidential nomination to Gerald Ford, but it was after midnight and Reagan was a defeated candidate, so his words didn’t get much attention. In “President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime,” I quoted the well-informed Strobe Talbott as describing Reagan as “a romantic, a radical, a nuclear abolitionist.” This was not praise from Talbott, an advocate of traditional deterrence. Reagan’s concerns about nuclear war reflected a stew of influences from science fiction to Armageddon. These crystallized into an epiphany on July 31, 1979, when Reagan toured the headquarters of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) at Cheyenne Mountain in Colorado. After viewing the network of radar detectors designed to warn of a surprise attack, Reagan asked the commanding general what could be done if the Soviets fired a missile at a U.S. city. Nothing, the general told him, except to give the city that was about to be destroyed a few minutes’ warning. Reagan was shaken. This incident was a probable inspiration for the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) that Reagan proposed as president. It was first and vividly recorded by Martin Anderson, who accompanied Reagan on the NORAD visit, in his book “Revolution.” I don’t know if Mann is aware of the incident or even of the book, for “The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan” surprisingly lacks a bibliography.

As to Reagan’s overall intentions, there is no doubt that he saw the military buildup he promised as a candidate and promoted as a president as a means to an end. On June 18, 1980, when Reagan was the presumptive presidential nominee, he was asked at a luncheon at The Washington Post if the military buildup he advocated would intensify the arms race. Reagan agreed that it would but said this was desirable because it would bring the Soviets to the bargaining table. In his first presidential news conference, on Jan. 29, 1981, Reagan said he favored “an actual reduction in the numbers of nuclear weapons.” On April 24, after lifting the grain embargo that President Jimmy Carter had imposed on the Soviet Union, Reagan over the objections of Secretary of State Al Haig wrote Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev an impassioned letter calling for a “meaningful and constructive dialogue which will assist us in fulfilling our joint obligation to find lasting peace.” Later that year Reagan embraced the formula of “zero-zero” that became the framework for U.S.-Soviet nuclear arms negotiations.

Mann mentions none of this except the letter to Brezhnev, and that in passing in a single dismissive sentence. He acknowledges, however, that the basic reason no U.S.-Soviet negotiations occurred in Reagan’s first term had more to do with the Soviet Union than with the United States. Brezhnev, who brushed off Reagan’s letter, was a faltering leader. He died in 1982 and was replaced by Yuri Andropov, seriously ill when he became leader of the Soviet Union. He died 15 months later and was replaced by Konstantin Chernenko, also on his last legs. Chernenko lasted little more than a year. “They kept dying on me,” Reagan said when asked to explain why he didn’t meet with a Soviet leader in his first term. It was an odd locution, but Reagan was right. It wasn’t until Gorbachev, vigorous and reform-minded, came to power in 1985 that it was realistically possible for any U.S. president to negotiate with a Soviet leader.

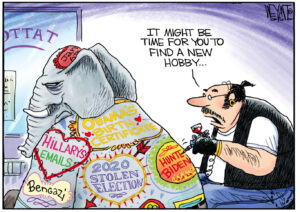

Negotiate Reagan and Gorbachev did, at summits in Geneva, Reykjavik, Washington and Moscow. There were ups and downs along the way, partly because there were factions in both the United States and the Soviet Union that were opposed to meaningful negotiations and partly because Reagan was reluctant to confine SDI to laboratory testing, as Matlock says he could have safely done. Disagreement on this issue caused the breakup of the Reykjavik summit, but the progress made there and in the aftermath led to the breakthrough treaty reducing intermediate-range nuclear weapons in Europe. Not only was it the first U.S.-Soviet treaty to provide for destruction of nuclear weapons, it also provided for on-site monitoring of the process. Even before the ink was dry on this notable document, Reagan’s supposed soul mates in the conservative punditry—especially William F. Buckley, George Will and William Safire—were accusing him of perfidy for trusting Gorbachev and were supporting Sen. Jesse Helms, R-N.C., in his battle to block ratification of the treaty. For years conservative pundits had risen to Reagan’s defense whenever liberals questioned his motives or his intellectual candlepower. Now they became derisive—Will accused Reagan of “moral disarmament”—or even abusive, as in the case of Howard Phillips of the Conservative Caucus, who described Reagan as “a useful idiot for Soviet propaganda.” Mann usefully revisits this ground, although he doesn’t seem to realize that Reagan was confident of prevailing. Reagan knew intuitively that no one could sell the American people on the notion that he was soft on communism—and the surveys that were taken for him regularly by in-house pollster Richard Wirthlin confirmed his views. A Wirthlin poll in January 1988 found that six of 10 Americans (59 percent) thought the INF treaty must be in the national interest if Reagan thought it was. The treaty itself was favored by 79 percent. This overwhelming public support for the treaty assured that Helms would fail, and he did. The INF treaty was ratified on a 93-5 vote on May 27, 1988, just before the Moscow summit.

But it wasn’t just the far right that opposed Reagan’s summitry. Mann makes a singular contribution by digging up a memo at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library that recounts a secret Nixon meeting with Reagan at the White House on April 28, 1987. Nixon’s message was that Gorbachev, although smoother, had the same evil intentions of prior Soviet leaders. Reagan did not mention this meeting in his diary or his memoirs, but he could hardly have been impressed by it. At the time of the Nixon visit, Secretary of State George Shultz had just returned from a meeting with Gorbachev in Moscow that set the stage for the INF treaty. Nixon writes that he sensed a “coolness” in Reagan and, as he often did, disparaged Reagan’s command of issues. Reading the memo now, however, makes one wonder what planet Nixon was living on. “There is no way he [Reagan] can ever be allowed to participate in a private meeting with Gorbachev,” Nixon wrote. But Reagan had already done that at Geneva and, as the transcripts of the Reykjavik summit show, had held his own with Gorbachev, which was no small feat. Furthermore, Reagan had dismayed conservatives including Pat Buchanan, who then worked for him, immediately after the Geneva summit in 1985 by saying that Gorbachev was the first Soviet leader who wasn’t out to dominate the West. Later, Reagan told me that he considered Gorbachev a “moral man.”

Mann’s book is a reminder that Reagan followed his own course, one that he had long charted. He was much helped by Shultz, to be sure, and by moderates on his staff such as Michael Deaver and by Nancy Reagan, but he followed his instincts against not only his fellow conservatives but the “realists”—as they thought of themselves—such as Nixon, Henry Kissinger and Brent Scowcroft, all of whom misread the leaders of both their country and the Soviet Union.

Reagan and Gorbachev deserve considerable credit for following their instincts in trying to reduce the threat of nuclear war, as has been eloquently said by Alexander Bessmertnykh, a high-ranking Soviet official during the Reagan-Gorbachev summits. “The experts didn’t believe, but the leaders did,” Bessmertnykh commented at a retrospective Princeton conference, published in a valuable 1996 book called “Witnesses to the End of the Cold War.” In our current dangerous multipolar world, it’s worth remembering that enlightened leaders can make a difference—and to hope that President Obama pursues his idealistic goal of a world free of nuclear weapons even if his critics consider it a fantasy.

|

Lou Cannon, a former Washington Post reporter, has written extensively on Ronald Reagan. His books on the 40th president include “Reagan’s Disciple: George W. Bush’s Troubled Quest for a Presidential Legacy” (2008), with Carl M. Cannon; “Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power” (2003); and “President Reagan: The Role of a Lifetime” (1991). |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.