Lawrence Bender: The Truthdig Interview

Bender, the producer of every Quentin Tarantino movie, describes how he produced the Al Gore global warming documentary "An Inconvenient Truth." Check out: Why he thought a guy nicknamed "The Robot" would a compelling documentary subject His take on Gore's inability to capitalize on global warming when he was in office Bender's recognition that climate change barely registers on most voters' minds

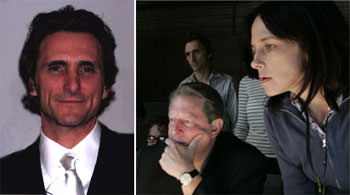

Editor’s note: The following is an edited conversation between Truthdig managing editor Blair Golson and Lawrence Bender, the producer of the Al Gore global warming documentary “An Inconvenient Truth,” which opens in Los Angeles and New York on Wednesday, May 24.

SEVERAL years ago, the idea of making a wide-release movie out of Al Gore delivering an hour-and-a-half lecture might have struck some people as slightly batty. After all, the nickname he earned during the 2000 presidential campaign was “The Robot” — hardly a selling point for a guy whose rhetoric would have to carry an entire movie.

Nonetheless, there he was this past weekend at the Cannes Film Festival, posing for pictures on the red carpet in support of “An Inconvenient Truth” — a film cut almost entirely from the footage of Gore’s lecture on the dangers of global warming.

The presentation is one that the former vice president has given around 1,000 times since the late 1980s, but it wasn’t until early 2005 that it caught the attention of a Hollywood producer who glimpsed the cinematic potential of Gore’s traveling show.

That producer, Lawrence Bender, had exploded onto the Hollywood scene in 1992 as the producer of Quentin Tarantino’s first film, “Reservoir Dogs,” and produced every Tarantino film since — including “Pulp Fiction” and the two “Kill Bill” movies. And although gory violence is indeed one of his hallmarks, he has also made a career of tackling projects with more social conscience: “Good Will Hunting,” “White Man’s Burden” and “Voces Innocentes” (“Innocent Voices”).

More recently, he was one of the driving forces behind “The Detroit Project” TV ads, which drew attention to the foreign policy ramifications of driving gas-guzzling SUVs.

With “An Inconvenient Truth,” Bender tackles an issue of, well, earth-shattering importance: global warming. And whereas the makers of “The Day After Tomorrow” pumped a reported $175 million into that depiction of catastrophic climate change, Bender’s version is somewhat more stripped down. The majority of the movie exhibits Gore delivering his lecture to an audience at a relatively small theater in Los Angeles. But the message is no less startling than that of the fictional movie — it’s more, because it derives from essentially uncontested scientific fact. With the aid of a 70-foot digital screen that Bender commissioned specifically for the movie, Gore displays a dizzying array of graphs, facts, figures and slideshows that leave little doubt of the calamity facing our planet due to the stratospheric levels of heat-trapping carbon dioxide in our atmosphere.

But lest Bender allow the entire film to rest upon Gore’s delivery, the producer also sprinkles the film with narrative dramas from the former presidential candidate’s life — such as the death of his sister Nancy to lung cancer, which Gore ties into the film’s message by highlighting the disingenuous marketing strategies of industries like tobacco and coal.

Bender and his production team have orchestrated a grass-roots marketing campaign that relies heavily on small informal screenings for influential groups and individuals. The movie’s almost uniformly positive buzz and advance press have stoked enormous amounts of “will he or won’t he” speculation about a possible 2008 White House run by Gore. But the man who says during the film that he “used to be the next president of the United States,” has repeatedly said he isn’t running.

Truthdig managing editor Blair Golson spoke to Lawrence Bender in Los Angeles on the eve of his trip to Cannes. Bender discussed how he became convinced that Gore would make a compelling documentary subject; the reasons why Gore didn’t capitalize on this issue when he was in office; and the sad fact that despite all of Gore’s efforts, pollsters still finds that global warming barely registers on most voters’ minds.

Blair Golson: How did this project come about?

Lawrence Bender: Basically what happened is that [environmental activist] Laurie David brought Gore here to do his presentation in L.A. I hadn’t seen it, and when you see him do it, it’s so definitive on global warming that it makes you want to take action. Everyone comes out saying, “What can I do?” I’m a filmmaker, obviously, and I immediately felt that this presentation could be made into a movie. And I think a light bulb went off in my head. I thought it could be made much more visual — instead of thousands of people seeing this, millions of people could see this; and we could create a tipping point if we created a movie out of this.

To be fair, Gore isn’t exactly known for having the most captivating rhetorical skills. What made you think that his delivering a lecture on-screen for an hour and a half would make for a good movie?

When I saw him actually give the presentation, I felt he was funny, he was passionate, grounded, emotional and that from a purely cinematic point of view he had all the things that would make a character in a movie interesting to watch.

Even as a lecture? Because I can’t think of many movies that stick so closely to the lecture format.

When I saw him do the presentation, I felt that between the slideshow, his personality, and who he has become as a human being, he would really come through on screen.

But didn’t his personality come through on screen during the 2000 presidential debates? In a sense America has had a long time to get to know him on screen. But you thought this would be different because…?

I just know that the Al Gore that we saw during those debates — I didn’t know him personally then, so all I knew was what I was seeing [during the lecture]. And watching him, I thought, “This guy is a transformed being, and I want to capture this on film.”

I know that Gore says he isn’t running in 2008, but Steve Forbes started a national debate on the flat tax with his candidacy. By any measure, Gore is a tremendously more plausible candidate than Forbes was. Don’t you think his running can be a way to bring the debate to the fore?

It could certainly. All I can tell you is that he’s been very clear with us that he’s not running. Certainly that’s not the reason why we approached him to make this movie, nor is it the reason why — well, he didn’t come to us to make the movie. Do I think he’d be a great candidate? Of course. Would I like to see him president? Of course. But right now this is what he’s doing. It seems like, for him, he’s creating a lot of traction on an issue that he’s very passionate about, and making a real difference.

Why do you think Gore wasn’t able to get more traction on this issue when he was in office, and held the reins of power for eight years?

I think it had a lot to do with the Republican Congress. They kept pushing back. The good news is that there were a lot of environmentally unfriendly bills that the Republican Congress was trying to pass that [the Democrats] were able to stop. But the bad news is that the Democrats couldn’t do what should have been done on global warming. And now, this administration is really horrific on this issue.

You’ve racked up a lot of awards for your more commercial films. Have you been recognized for advocacy projects before this one?

Last year I got a Torch of Liberty award from the ACLU for different movies I made on issues that are timely and relevant today.

Can you name a few?

I did one called “Chumscrubber” that dealt with the proliferation of prescription drugs; “Innocent Voices,” about a 12-year-old boy in the civil war of El Salvador; even with “Good Will Hunting” I had different therapists tell me that it was an important movie for people who deal with teens. I did a movie called “White Man’s Burden” with John Travolta and Harry Belafonte; it wasn’t the greatest movie, but essentially it was about what America would be like if Africans had settled here and we were an Afrocentric country as opposed to a Eurocentric one.

Who approached Gore, and how did that happen?

We put a team together. We had: me, the, kind of, big Hollywood producer; Laurie David, the activist; Scott Burns, who directed the “Got Milk?” commercials and the Detroit Project commercials; Leslie Chilcott, who was going to handle all the heavy lifting; and Davis Guggenheim, the director who was going to visually put this together.

We all went up to San Francisco last May to pitch Gore, and when we met him we were pretty much in a different city every day doing his presentation. And we said to him: “Look, you’re crisscrossing the country doing this. What if we made a movie and got millions of people to see it?” He got it immediately.

What was your first impression of Gore?

We were immediately taken by how personal and emotional he was in person. So if we didn’t feel it before, we certainly got it then in the room. And the other thing we felt was that there was an urgency, that this had to be done quickly, because it’s an urgent issue, and we wanted to get this thing out within a year. So we literally dove right in. We brought it to Jeff Skoll, who ended up putting up the money. They seemed like the obvious choice because of the movies they make. Skoll’s company, Participant, financed “Good Night, and Good Luck,” and “Syrianna.” They got 11 Academy Award nominations last year; but their mission statement is to make movies with social relevance.

So they’re the main financial backers?

They’re the financial backers.

Oh, OK.

So we got into Sundance, standing ovations there, and Paramount Classics bought the movie out of Sundance. That’s the whole background on it.

What kind of marketing and what kind of rollout is the movie getting?

The movie opens May 24th in L.A. and New York, and it goes wide through June. It’s a very big grass-roots marketing campaign, involving all different kinds of social organizations, environmental organizations, religious organizations, many different bloggers, Internet portals, be it MySpace, Yahoo, Google, Netflix — all these different groups are helping to get the word out on the movie. Al is doing the nighttime and morning shows. He’s tireless. He’s going around the country, city by city.

Where are the profits going? I mean, are you guys all going to get a fleet of Hummers instead of points on the back end?

Exactly [laughs]. Most of the profits are going to go to a fund to make people aware of the planet crisis.

What’s been the most challenging thing about making this whole thing happen?

The most challenging thing is — I mean it’s kind of one of those miracle movies that was made on a very, very small budget.

How much was the budget?

Ya know, I don’t like to talk about the budget.

OK, no problem.

It’s a documentary, so believe me, it’s a small budget. The most challenging thing is that we needed to do this now. We wanted to go into production early [in the] summer because we wanted the movie to come out early [the] next year. So we met with Al Gore in May [of 2005], and we’re screening it seven months later at Sundance. It was a pretty intense schedule.

What was your thinking on including in the film narrative snippets of tragedies in Gore’s life?

When I saw the presentation, I said to myself: ‘OK, this is a movie. I know it can be made more visual, but we need to find a personal way in. And that meant hours and hours and hours of interviews. At one point Gore said it felt like we were making “Kill Al Vol. 3.” It was grueling, and we did it in a very short period of time. We followed him to China, we shot in Nashville, Stanford — we went all over the country. It was a lot of travel in a very short period of time. And they had to get this thing edited and cut starting in January, and ready to screen in May. That’s like a seriously tight schedule. So the logistics of pulling it off with a low budget were really difficult, and if there’s one person who gets credit, it’s Leslie Chilcott, because she really pulled it together.

By movie’s end, the problems facing our environment seem so severe that it almost seems silly to think that improving gas mileage from 25 to 35 miles per gallon would have much of an impact. You get the feeling that the entire industrial world would have to stop being industrial before we could start to arrest, if not reverse, the damage being done to the planet. How much truth is there to that?

There’s a lot that has to be done. And it’s not just one thing. I mean, yes, the fuel efficiency of cars has to dramatically change. We need to go from gas to biofuel, ethanol. We need solar, wind, other renewable-energy technologies. We need to carbon capture and sequester the carbon dioxide coming out of the smokestacks. There’s not one solution. The thing that’s challenging about this is that we need solutions at every level, every area. One of the things I believe could happen on a grass-roots level is for people to learn what it means to have a carbon footprint. Your carbon footprint is the car you drive, the house you live in, the way you travel. You can calculate how much carbon dioxide you put out by living. If you go to our website, climatecrisis.net, you can calculate it yourself and see how you can reduce your carbon output. And then for a very small amount of money you can buy a carbon offset — and make yourself carbon neutral. And if you get your friends to become carbon neutral, and your family, your community — all of a sudden, you could create a whole grass-roots thing around being carbon neutral. Our movie was carbon neutral. We bought carbon offsets. Our premiere was carbon neutral. You can do things to become carbon neutral.

What’s the scale of reforms that America and the world would need to enact to halt this problem, if not reverse it?

It’s one step at a time. We just need to start. When we did get the world to address the ozone problem, we started off with one treaty, which, in and of itself, was not enough to reduce the CFCs that we were emitting. But they kept cutting again and again until we got to a place where those chemicals in the atmosphere are way, way down. The ozone issue is being addressed on a worldwide basis. Right now the United States and Australia are the only countries that haven’t signed the Kyoto Protocol. You can argue that it’s not good enough, but it’s a start; and once you have a start, you can continue to address the problem.

Have you screened the movie for any people like industrial barons or car company owners that you’d assume might be hostile to the film’s message?

We haven’t screened it for any car companies, but we are screening it for all different groups of people. We’ve screened it for evangelical leaders, and there’s a whole bunch of evangelical leaders who now are supporting this issue. So we are trying to go across the board. This should be a nonpartisan issue, obviously.

But no screenings for people who you know would be natively unreceptive to the message?

[Chuckles.] Honestly, right now, it’s like one step at a time. Right now the idea is to get the word out on the movie. So as a company, we’re trying to market the movie. And as we progress, we’ll be screening the movie. We want to screen it for as many different types of people as possible — different areas, the head of General Electric [Jeffrey Immelt]. Last year he came out publicly and said that this is an issue that needs to be addressed. So there are big industry leaders that are addressing this. And I think this year will be a perfect storm, with this movie being part of it, between Katrina and the gas prices and the war on Iraq and the storms. I think this movie is going to be part of a whole perfect storm battle to create a tipping point on this issue.

Really? Because you anticipated my next question. Global warming and the environment hardly register at all in some polls about voters’ concerns going into the 2006 midterm and 2008 elections. Why do you think that is?

I think it’s because of that frog in our movie: You put a frog in cold water and slowly heat it, he doesn’t know that things are heating up around him and jump out. As opposed to throwing a frog in a pot of boiling water, and he’ll jump right out. That’s a visual look at what’s around us: Global warming does not affect you in everyday life. The problem is that if you wait until it affects your everyday life, it’s too late. Because once that carbon dioxide is up in the atmosphere, it stays up there for like 100 years. And once it’s too late, it’s really too late. It’s going to take real leadership on all levels to make people aware that this issue is potentially the greatest threat we’re facing this century.

Of course terrorism, jobs, healthcare — these are things that you deal with on a daily basis, so they’re going to be high on your priority list. And what’s exciting about this: The solutions to global warming help create jobs, help the economy, are good for national security, are good for your healthcare system…. That’s why I’m so taken by this issue. The solutions offer so many different ways to help.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.