Keeping a Watchful Eye: A Half-Century of the Residents

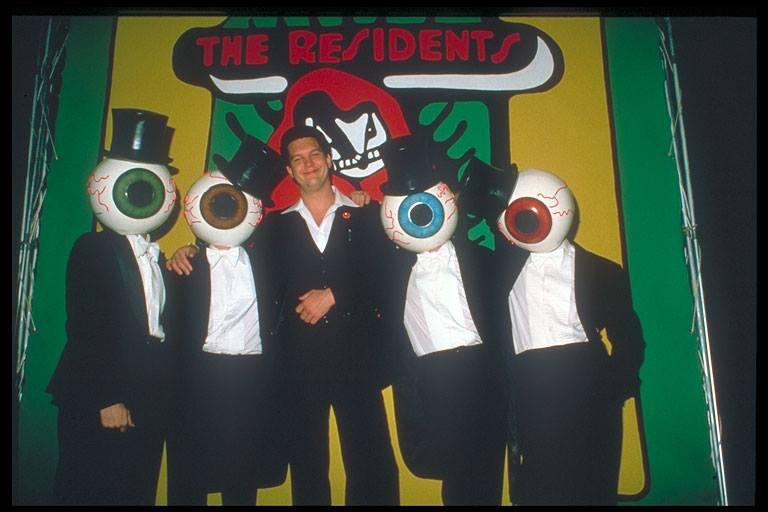

When you weren’t looking, four anonymous eyeballs changed your world. The Residents. Photo: Courtesy of The Cryptic Corporation

The Residents. Photo: Courtesy of The Cryptic Corporation

On April 19, 2023, The Residents closed their concert at San Francisco’s Great American Music Hall with “Nobody Laughs When They Leave,” a song off their 1990 album “Freak Show.” The hometown gig was the final stop on what had been a grueling three-month, 46 stop 50th anniversary tour they’d dubbed “FacelessForever.” The official tour t-shirt for sale at the merch table was emblazoned with the legend, “Holding Up the Underground Since 1972.” It was both an audacious boast and a self-deprecating understatement.

This past year a number of once-popular, even legendary bands founded in 1972 emerged from a decades-long hibernation, re-forming to undertake 50th anniversary tours of their own. Roxy Music, The Doobie Brothers, Blue Oyster Cult and a fistful of other old-timers got in on the game, wowing fans with faithful renditions of all their smash mid-’70s hits. In a majority of cases the term “re-form” was a bit of a misnomer, considering most could claim only one or two original members supported by a crew of pickup hacks. As prominent as these bands may have been in, say, 1976, by 2023 they had devolved into tired state fair nostalgia acts.

In contrast, The Residents not only toured with all four original members, but having never had the luxury of a dormant period, their Greatest Hits set featured material stretching from their debut album through 2020’s “Metal, Meat & Bone.” And unlike those others, despite that intervening half-century, they hadn’t aged a day.

All this sounds like I’m talking about The Residents as if they were a band. That’s not quite accurate. They play music, release albums and go on tour, but they aren’t a band. At least that’s the claim made by their management team, The Cryptic Corporation. At other times they insist The Residents are “Huge International Rock Stars.” Sometimes they’re an avant-pop art collective, while at still other times, the group has been known to refer to themselves as traveling t-shirt salesmen or, for some reason, chiropractors. The Residents are weird that way. The Residents are weird in most ways, but this takes a bit of explaining.

Even if you’ve heard the name it’s likely what you know about The Residents doesn’t venture much past their iconic top-hatted eyeball heads.

If you haven’t heard of The Residents, don’t feel bad. Well, not too bad anyway. They haven’t been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. They’ve never graced the cover of Rolling Stone. They’ve yet to win a Grammy. They haven’t cracked Billboard’s Hot 100 and have never performed on “Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve.”

Even if you’ve heard the name it’s likely what you know about The Residents doesn’t venture much past their iconic top-hatted eyeball heads. That’s okay too. Even their most obsessive diehard fans couldn’t name a single member of the group, because they don’t have names. No names, no faces, no race, and no gender. Yet as deliberately obscure as they remain in mainstream terms, a number of familiar cultural artifacts, phenomena, and figures we now take for granted can be blamed directly on The Residents, whose covert influence has impacted music, art, film, performance, literature and digital media. It’s also resulted in more than a few institutionalization’s, but there’s no need to dwell on that.

Between roughly 1966 and 1969, a small circle of eccentric friends fled the suffocating Bible Belt mentality of Louisiana Tech and emigrated to the freewheeling psychedelic wonderland that was San Francisco in the late ’60s. Four of them settled in a small apartment above an auto body shop in San Mateo and, as it seemed the thing to do at the time, began experimenting with photography, silkscreening, painting, intriguing chemical compounds and other expressions of the artistic impulse. None of what we’ll call the Pre-Residents knew how to play an instrument, but they recalled the John Cage quote, “Knowing how to play instruments is fine, but it just gets in the way of the truly great.”

They scoured local thrift stores and gathered used and occasionally broken instruments, as well as other objects that made interesting noises. Back in the apartment, they began recording themselves as they banged and twanked on their new acquisitions, later editing the cacophonous and incoherent tapes into at least quasi-musical compositions with titles like “The Ballad of Stuffed Trigger” and “The Mad Sawmill of Copenhagen, Germany.”

Around this time, they were also introduced to a Bavarian avant-garde composer and music theorist they came to know as The Mysterious N. Senada. In an era in which the public personas of, say, Andy Warhol, Mick Jagger or William Burroughs often eclipsed the actual work they produced, Senada advocated a Theory of Obscurity that held it was the work and not the artist that mattered, that the artist should remain as invisible as possible. He also argued an artist produces his or her best work in complete isolation, with no thought given to any potential audience or reigning cultural trends. Those two rules would determine the course the group would follow for the next half-century, beginning with the decision to remain anonymous.

In 1971, deciding it was time to take the world by storm with their exciting new sound, they sifted through hundreds of hours of their naive and primitivist experimental recordings, compiling a demo tape of what they considered their most radio-friendly toe-tappers, like “Baby Skeletons and Dogs.” Certain they were on the brink of a multimillion-dollar major label deal, they sent the demo off to Warner Bros. Records. A & R executives at what was considered the industry’s most adventurous label, citing a difference of opinion regarding what did or did not constitute “radio-friendly,” rejected the tape. As the tape had been submitted anonymously, the return package was addressed simply to “Residents.” Recognizing it was the perfect name for an anonymous band, the group immediately adopted it for themselves.

Realizing their dreams of a major label contract were silly, at best, in 1972 the newly-christened Residents launched their own indie label, Ralph Records, with a four-song double single called “Santa Dog.” It took the form of a Christmas card that they mailed out to friends, luminaries and Richard Nixon. The songs were at once catchy, abrasive, confounding, occasionally profound and quite unlike anything else anyone was hearing at the time. It also marked a great musical leap forward from what had appeared on the Warner Bros. demo. It seemed someone in the shadowy collective was getting a handle on rhythm and something resembling pop song structure.

After 1972, things quickly grew murky. In a world overrun with self-promoters begging to be recognized and aging celebrities struggling to remain famous, The Residents militantly protected their anonymity. They refused to give interviews, leaving that unpleasant task to representatives of The Cryptic Corporation, and have never been photographed except when disguised in elaborate costumes, like the above-mentioned eyeball masks.

Working within a self-imposed bubble, they developed a singular if not downright alien aesthetic that was reflected not only in their (mostly electronic) music, but their visual art and video work as well. Outsider artists and visionaries in the truest sense, operating in a vacuum may have worked to their advantage. Remaining uninfected by the parade of the outside world’s passing fads left The Residents with a clarity that allowed them to latch on to possibilities no one else had noticed.

Three years before “The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” six years before “Eraserhead,” and long before Midnight Movies became a national phenomenon, The Residents were shooting what they envisioned as an epic cult film. “Vileness Fats” concerned one-armed midgets, a pair of Siamese twin tag team wrestlers, a band of renegade bellboys who occasionally disguised themselves as pieces of meat, a schizophrenic religious leader and an eternal Indian priestess. A few other things too. With 14 hours finished and a long way to go yet, the project was abandoned in 1976. That same year they made another, much shorter film that, unlikely as it seemed at the time, changed everything. Whether it was for better or worse is your call.

“The Third Reich ’N Roll,” their second full-length album, was a densely collaged soundscape composed of two dozen less than respectful covers of ’60s pop hits ranging from “It’s My Party” to “The Ballad of the Green Berets.” To promote the album, they shot a Dadaist short film which, if unintentionally, still shocks more sensitive viewers to this day. Synchronized with a condensed version of the album, the central image features The Residents dressed in newspaper suits, playing instruments wrapped in newspapers against a backdrop of still more stacked newspapers. The rest involved some stop-motion animation and, in keeping with the overall theme of the album, some Nazi imagery. Remember, music video was not a thing at the time, so it was taken as a bizarre little art film. The video went on to be included in several short film festivals, and whispered legends about these enigmatic oddballs began to circulate. Despite their best efforts it seemed some people were starting to pay attention.

Four years later, in 1980, The Residents released “The Commercial Album,” a collection of 40 songs, each one minute long. To promote the record, they shot four equally bizarre videos in four different styles, which they released as a package they called “One-Minute Movies.” Then two things happened. New York’s Museum of Modern Art added “One-Minute Movies” and the “Third Reich ’N Roll” short to their permanent collection, hailing them as the first true music videos ever made. A year later, in 1981, MTV was launched. Because very few bands were making videos when the music channel premiered, The Residents and other weirdies like Talking Heads, DEVO and The Buggles were in heavy rotation until the rest of the world caught up.

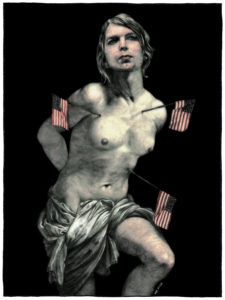

Not counting live albums, compilations and EPs, to date The Residents have released 50 studio albums in nearly as many styles. While immediately recognizable, no two sound quite alike and most are concept albums of one form or another. They’ve released a collection of songs inspired by often overlooked Bible stories, an avant-garde opera, a dialectical history of American popular music, a portrait of a sex addict who wants to be a circus clown, a soundscape exploring the intrusion of Western consumerism on Inuit culture and so forth. 1988’s “God in Three Persons,” a musical epic poem concerning a pair of Siamese twins with healing powers, even presaged the present discussion about gender fluidity. As inimitable as the subject matter, their wildly eclectic and ever-evolving sound has found them credited as both inspirations and innovators across a spectrum of musical genres including New Wave, trance, world fusion, modern classical, electronica, punk, industrial and the lounge music revival.

Outsider artists and visionaries in the truest sense, operating in a vacuum may have worked to their advantage.

Beyond styles, they were also pioneers in the use of now-commonplace techniques and technical innovations. The first (intentional) mashup appeared on “The Third Reich ’N Roll,” when they combined “Hey Jude” and “Sympathy for the Devil.” While ubiquitous today, The Residents have been employing audio samples from the beginning. “Santa Dog” was held together with samples, the specific James Brown horn riff they dropped into “Third Reich ’N Roll” is now considered a hip-hop staple. And the less said about the horrible, mean things they did to the Beatles on 1977’s “Beyond the Valley of a Day in the Life,” the better.

Taking that “avant-garde” label seriously, The Residents have also been trailblazers when it comes to exploiting the possibilities of emerging technologies. When the first commercially available digital sampler, the E-Mu Emulator, was released around 1980, they snagged the fifth one to roll off the assembly line. The same year Apple premiered the Mac, The Residents released the first album with a cover designed on a computer. Shortly thereafter they released the first music video to use computer graphics, and in 1988 the first fully computer animated music video. They were fiddling around with MIDI long before the system was an essential addition to every basement studio everywhere.

They have been digital pioneers at every turn. When the internet was in its infancy and dial-up was the only available option, they were among the first to host an Electronic Bulletin Board, which would in later years evolve into today’s chat rooms and message boards. When interactive CD-ROM seemed poised to become the next generation home entertainment platform in the early ’90s, The Residents grabbed the opportunity to transform the technology — until then of use only to businessmen, economists and scientists — into an artistic medium as viable as paint or film. Between 1994 and 1998 they produced three award-winning animated CD-ROMs, “Freak Show,” “The Gingerbread Man” and “Bad Day on the Midway.” When the CD-ROM market crashed at the end of the decade with the advent of DVDs, more than a few people, acknowledging their impact on the form, had come to refer to CD-ROM drives as “Residents Players.”

By the time the term “podcast” came into wide usage they’d already posted two, one about the group itself and the other a disturbing serialized crime drama.

Always dancing that blurry line between high and low art, their paintings, photography, costumes, props and groundbreaking video work have been held in respected art institutions both in the U.S. and Europe, including several retrospectives at MoMA. Hell, even their live shows, which tend to be more subversive theatrical spectacles than concerts, have been called a major influence on contemporary performance art.

Yet after 50 years, and despite some wild and fanciful guesswork, nobody really knows who or what they are.

Little if any of the above is part of our collective mainstream cultural consciousness. Whether The Residents are bitter or annoyed about the lack of recognition is unknown. It’s entirely possible that, in accordance with N. Senada’s teachings, they simply haven’t been paying attention. Still, if any public validation of the major impact they’ve had on the culture was necessary, it can be found in director Don Hardy’s 2015 documentary “Theory of Obscurity.”

They have been digital pioneers at every turn.

In the film a veritable gaggle of notables step forward to testify to the influence The Residents have had on their lives and work. Before teaming up with Teller, Penn Jillette collaborated with The Residents on several projects, including acting as the confrontational narrator of their first tour, “The Mole Show.” In 1978, “Simpsons” creator Matt Groening was a charter member of the first Residents fan club and wrote the first unofficially official band history. Before he won a bunch of Emmys for his “Pee-Wee’s Playhouse” set design, famed comics artist Gary Panter created some album covers and one-off art prints for Ralph Records, wrote a column for the mail-order catalog and conscripted The Residents to be the backing band on his first album. Other noted comics artists, Steve Cerio and Matt Howarth, have centered much of their work around The Residents. Members of Primus, Ween, Talking Heads and DEVO all admit to the profound influence The Residents have had on their own music, and the list of musicians known or unknown who could claim the same thing is staggering. Scanning down the list of Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees and nominees, I nearly gagged at the number who owed them a debt of gratitude. (They also have some high-profile literary cameos: Thomas Pynchon dropped a Residents reference into his 2006 novel “Against the Day”.)

If not for The Residents’ visionary machinations, we wouldn’t have MTV, “The Simpsons,” Penn & Teller, hip-hop, underground raves, computers, half of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees or the internet. Most significantly in terms of the culture as a whole, we must ask ourselves, if not for The Residents, would we be able to enjoy that clear homage “The Masked Singer” every Wednesday night at 8 p.m. on Fox? I doubt it.

Pretty impressive for a quartet of cockeyed hippies from northern Louisiana. Of course, it’s conceivable they’ve spent the last 50-plus years quietly executing a serpentine and diabolical plot to recast the whole world in their image. If this is indeed the case, The Residents may be the only ones laughing when they leave.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

Thank you Jim! God bless The Residents.