James Baldwin Won the Battle, but William F. Buckley Won the War

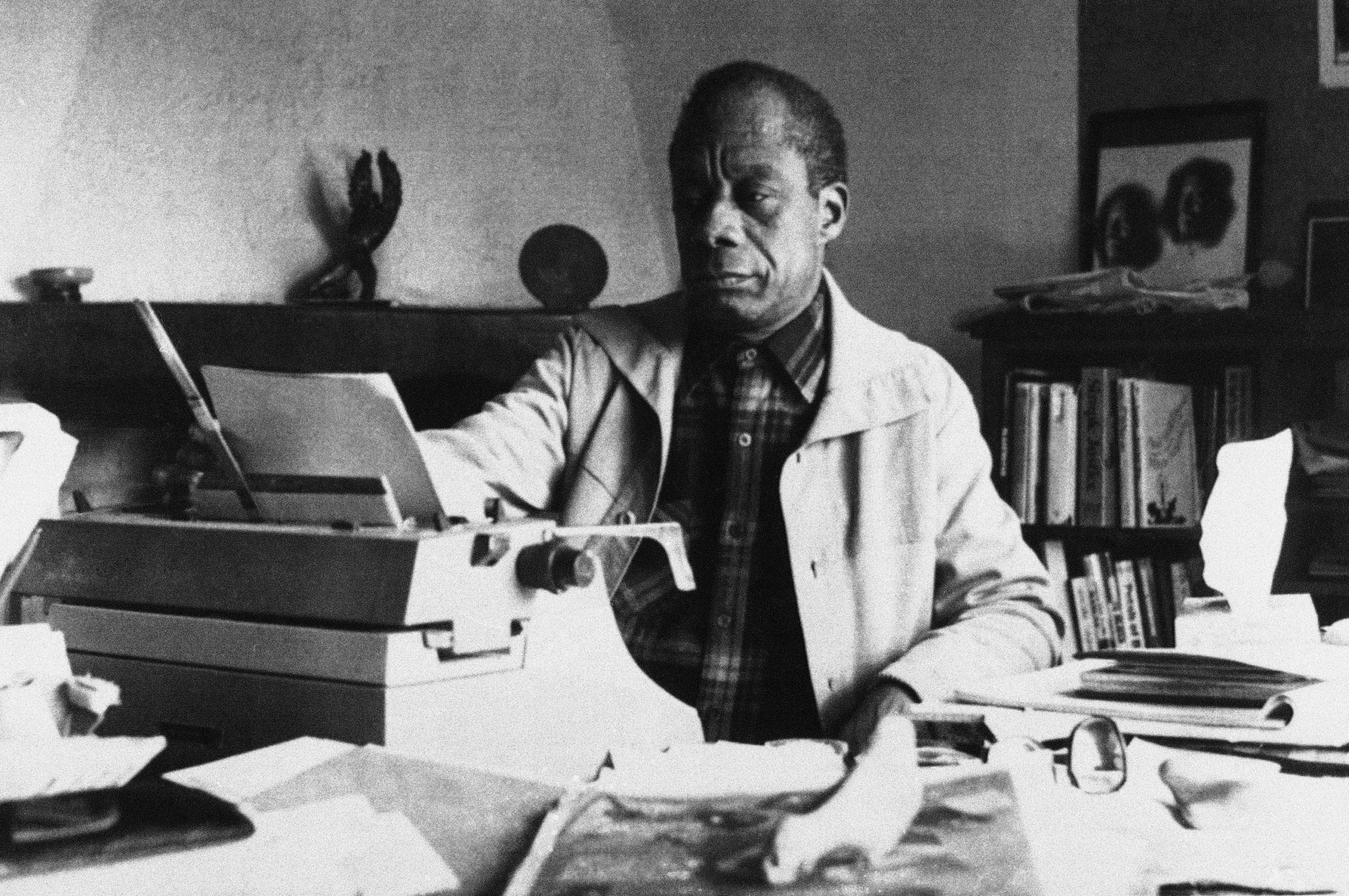

A new book explores the legacy of a momentous 1965 debate about race in America. James Baldwin at work in March 1983 in France. (Photo Pressenia / AP)

James Baldwin at work in March 1983 in France. (Photo Pressenia / AP)

To listen to Truthdig Editor-in-Chief Robert Scheer’s interview with “The Fire Is Upon Us” author Nicholas Buccola, click here.

On Feb. 18, 1965, three days before the assassination of Malcolm X, a few weeks before the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, and six months before the Watts riots, James Baldwin and William F. Buckley Jr. debated before the Cambridge Union Society at Cambridge University.

The proposition: that “the American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro.” Recorded by the BBC, the debate was edited down into an hour—including all of Baldwin’s speech but trimming Buckley’s—and broadcast. The show was shown later the same month in the United States by National Educational Television.

It’s hard to watch the debate, readily available on YouTube and elsewhere, and not feel the crackle in the room. Maybe I’m just imagining it; maybe it’s just historical hindsight. Or maybe not: BBC commentator Norman St. John-Stevas says it “could be one of the most exciting nights in the whole of 150 years of Union history.”

That crackle stays fresh in “The Fire Is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate Over Race in America” by Nicholas Buccola. Written with drive and abundant research (including a transcript of both speeches, featuring the first-ever complete published transcript of Buckley’s), “Fire” propels us through the lives and careers that intersected in that momentous face-off.

“While some of the rhetoric and policy debates have evolved,” Buccola writes, “the core issues that divided Baldwin and Buckley remain as relevant as ever.” In Buccola’s judgment, Baldwin won the battle, in his grasp of the causes and consequences of racial conflict, in a subtle masterpiece of a speech, and in the Union vote, which he won, 544-164. But Buckley won the war, Buccola says, losing the debate but shaping the conservatism that dominates the rightward politics of our time. I largely accept Buccola’s verdict, with one big reservation.

Buccola, the Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in Political Science at Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon, speaks in his acknowledgments of growing up in “a staunchly conservative Republican household,” with Cato Institute summer camps and an internship at the Heritage Foundation. Soon, though, “the study of history and political science led me to grow up from conservatism.” Note that slap at Buckley’s book “Up from Liberalism.”

The first five chapters sketch out the biographies of Baldwin and Buckley, the better to depict how the two men’s ideas took shape. Baldwin rises above his ghetto beginnings, managing, as per “Notes of a Native Son,” to avoid the “intolerable bitterness” he sees in his father. Instead he begins his celebrated turn toward the personal, toward hard-won compassion and hope.

By the time Buckley gets to Yale, his bedrock has formed. He is an oligarchist, an antidemocrat, a paternalist, a man who accepts that his caste—the white, wealthy elites that shaped the country from its beginnings—rightly holds power. Bids to challenge it must be fought at all costs. Those starting points colored all else, including his attitude toward racism (which he lamented, but to which he claimed there was no “solution”). Buccola is sensitive to the “fine line” Buckley “was attempting to walk on race.” Appalled at racial violence (and reportedly shaken to tears by the 1963 Birmingham church bombing), he was sympathetic to segregationist and states’-rights arguments. Yes, the Constitution guaranteed free speech—but political demonstrations, he felt, were often lawless riots, encouraged by the likes of Martin Luther King and Baldwin.

As of 2019, it is widely accepted that paternalism is racist. If I, white, am the parent, then you, black, are the child—less developed, less a person. You are to be guided, taught, and shaped by me, by right of my superior place and civilization. Buccola’s hair-raising summary: “Once they are civilized, then we will be willing to start talking about sharing some of our power.”

“Who or what gives you the right?” we might ask, and Buccola does. Buckley’s proud answer: my church, my fathers, and history itself.

These two men were far from exact complements. Buckley was the self-conscious, hard-charging leader of a movement. He founded The National Review and, as self-designated public gatekeeper, he built the conservative arena, peopled it with hand-picked thinkers and writers, and kicked out those he thought would harm the cause, including anti-Semites, Birchers, and violent bigots.

He was not, nor did he care to be, a great reasoner. He was not comfortable defending ideas. Buccola handily dissects the Buckley rhetoric—not a reasoned exchange but rather a weaponized performance aimed at showing the opponent in the worst possible light. He was a pugilist-provocateur.

In the age of Malcolm X and King, Baldwin was not a leader of crowds or marches. As he said to Julius Lester in a 1984 New York Times interview, “I have never seen myself as a spokesman. I am a witness.” Buckley was a policy warrior, but Baldwin was far less interested in haggling over details of social programs. As the latter said in a Jan. 15, 1979, speech in Berkeley, “I’m not really a tactician, I’m a disturber of the peace.”

Baldwin didn’t have readily identifiable politics. He trusted no theories; he wanted people to face up to what was inside of them and what was around them. It is much like Baldwin to write, “Clarity is needed, as well as charity, however difficult this may be to imagine, much less sustain, toward the other side.” Baldwin wanted to understand, and thus to avoid the sin of hatred. That sin, he felt, was the great mistake of the literature of protest.

With these two unlike men, we come at last to the jammed hall, the crackle in the room. Stevas calls Baldwin the “star of the evening” and says that Buckley, clearly less familiar to Stevas and the crowd, is “well known as a conservative in the United States.” In two climactic, exemplary chapters, Buccola guides us attentively through both speeches. Baldwin draws a standing ovation of more than a minute (“I’ve never seen this happen before in the Union,” Stevas says, “in all the years that I have known it”), Buckley half a minute of sustained, seated applause.

Buckley was right to feel he stood no chance that night. The audience was far more receptive to Baldwin and his elegant case against the oppression of black people, his insistence on their ironically indispensable place in American history, in making the American Dream even possible. And the onlookers didn’t buy Buckley or his rhetoric. His question-begging, ad hominem Molotovs, and shock tactics weren’t going to last long with them.

But if that February night 55 years ago wasn’t Buckley’s moment, Buccola suspects the present might be. “Buckley lost many battles over the years,” Buccola writes, but “racial politics helped him win the war.” Recent conservatism has enjoyed friendly breezes and bumper crops, managing to run the country despite losing the vote. And the aggressive, often sneering dismissal of liberal ideas—leaving them to the side, the better to attack—now enshrined in rightward rhetoric surely has its grandfather in Buckley. Whenever we hear conservative argument, we get a taste of him.

Whatever he thought of Trump the man, Buckley would have put up with Trump the winner. In the 1960s, noting the populist strain in Barry Goldwater’s support, Buckley made a devil’s bargain with populism, realizing it was indispensable for a conservative ascendancy. And so it was in 2016.

But if now is Buckley’s moment, it is even more Baldwin’s.

Baldwin’s work presages the #BlackLivesMatter movement and the related explosion of memoir, film, theater and poetry. He is even more important for my children’s generation than he was for mine. His legacy is unmistakable in one of the most widely read black memoirs in years, “Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Baldwin’s influence extends to many other books, including Jesmyn Ward’s 2014 memoir, “Men We Reaped,” and 2017 anthology, “The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race”; DeRay Mckesson’s “On the Other Side of Freedom: The Case for Hope” of 2018; and, in 2019, Darnell L. Moore’s “No Ashes in the Fire: Coming of Age Black and Free in America” and the recently released “Breathe: A Letter to My Sons” by Imani Perry and “How We Fight for Our Lives” by Saeed Jones.

These very different books all answer Baldwin’s call to witness in first-person testimonies of a life lived black, mind on fire. For an artistic coronation, there are films such as Raoul Peck’s 2017 documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” based on an unfinished script by Baldwin himself, or Barry Jenkins’ 2018 film adaptation of “If Beale Street Could Talk.”

If we grant Buckley’s presence in our politics, surely we must also grant Baldwin’s in our culture. If Baldwin is right, we’re never done; there’s no utopia, only the work of listening and witnessing. Crackling with intelligence, “The Fire Is Upon Us” ends with his words to Faulkner: “The challenge is in the moment; the time is always now.”

Dig, Root, GrowThis year, we’re all on shaky ground, and the need for independent journalism has never been greater. A new administration is openly attacking free press — and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Your support is more than a donation. It helps us dig deeper into hidden truths, root out corruption and misinformation, and grow an informed, resilient community.

Independent journalism like Truthdig doesn't just report the news — it helps cultivate a better future.

Your tax-deductible gift powers fearless reporting and uncompromising analysis. Together, we can protect democracy and expose the stories that must be told.

This spring, stand with our journalists.

Dig. Root. Grow. Cultivate a better future.

Donate today.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.