Iraq May Be the Easy Part

It may turn out that leaving Iraq is going to be easier than the calamities we confront when we turn our attention, as the president-elect likes to say, back to Afghanistan.On the international front, things are no easier for President-elect Barack Obama than they are on the front lines of the economic crisis that he vows to ameliorate first.

His priorities are Iraq and Afghanistan, complicated entanglements that were discussed — if at all — with glib simplicity in the final weeks of the presidential campaign. It may turn out that leaving Iraq is going to be easier than the calamities we confront when we turn our attention, as the president-elect likes to say, back to Afghanistan.

With the Iraqis nearing an agreement on a framework for the continued presence of some U.S. forces in their country and an Iraqi government desire to have most American troops out by 2011, a drawdown of some of the approximately 140,000 U.S. servicemen and -women deployed there now seems inevitable. For all the feverish political argument that has characterized the U.S. involvement in Iraq, beginning a withdrawal is, oddly enough, a pledge upon which Obama can deliver.

The point is not only to relieve Americans of the burdens of sacrificing precious lives and scarce dollars in the Iraqi desert, but to devote these treasures to the deteriorating situation in Afghanistan. It is not, as candidates blithely told us during the long presidential campaign, a matter of shifting troops. It is a matter of figuring out what — if anything at this point — can be done to keep Afghanistan from becoming what it was in the years leading up to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001: an impoverished and lawless place where seething tribal and regional rivalries, a corrupt central government, a flourishing poppy trade and an assortment of other social maladies too long to list make it ungovernable — a “failed state.”

“In Afghanistan, the problems are so big and the problems go so far beyond the military,” says Caroline Wadhams, a terrorism expert at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank. “It’s the drug trade, it is corruption issues, it is problems with the government not providing services for its people.”

Obama and his Republican rival, John McCain, both pledged during the campaign to augment the number of troops in Afghanistan — and both agreed that as many as 10,000 should be added to the 33,000 Americans already there. That was perhaps an admirable and bipartisan opinion. Except that there is an even broader agreement among U.S. military leaders, diplomats and international aid groups that Afghanistan is simply not reparable with military force. All that more forces can do, says Lawrence Korb, a Pentagon official in the Reagan administration and a military expert at the center, is reduce the need for the United States to rely on airstrikes for hitting Taliban and other targets — strikes that have killed hundreds of Afghan civilians and enraged the populace that once welcomed us as liberators.

No one really knows how much money or time or effort it will take to restabilize Afghanistan. A diversion of a few divisions from Iraq does not rebuild a nation, end corruption, prevent starvation or create jobs. The poverty rate among Afghans is 42 percent, according to the United Nations, and an additional 20 percent live just above the poverty line. Obama has talked about spending about $1 billion annually on development aid to Afghanistan. This is only a bit more than the Bush administration has devoted to it.

In political campaigns, we expect politicians to promise more than they can deliver. The exercise that journalists usually undertake to prove this point is to tally the cost of various domestic proposals for tax cuts or spending and say they “don’t add up.”

A promise to do things differently halfway around the word is not so easily reduced to arithmetic. And who really would pay attention, when the math of daily life — a paycheck lost to a layoff, a retirement account that is wiped out — is so much more immediate?

No one knows what was in the intelligence briefing President-elect Obama received for the first time on Friday, but it is not very hard to guess at its broad strokes. Officials have been warning for some time about a downward spiral in Afghanistan and in neighboring Pakistan.

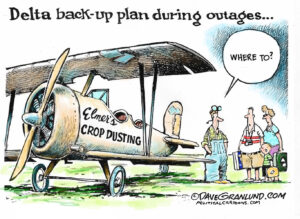

Obama has never minimized the complexity of the foreign policy challenges the next president will face. But the public must quickly come to understand that nothing is as simple as merely flying troops out of Baghdad and into Kabul.

Marie Cocco’s e-mail address is mariecocco(at)washpost.com.

© 2008, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.