Ignoring Our Economic Achilles’ Heel

While the president and Congress consider a cure for the Bush economy, they should look to the root of the problem: stagnant incomes.WASHINGTON — Whatever concoction President Bush and the Democratic-led Congress now cook up to minister to the ailing economy is likely to have a chicken-soup effect. Many people will feel better, and things might perk up.

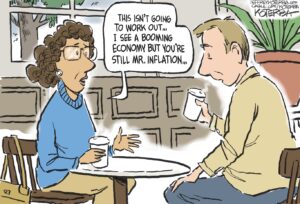

Still, the temporary boost will not cure an underlying disease that has been spreading for decades and which should be treated as a full-blown emergency. Depending on when — and if — a recession officially is declared, economic history seems as though it is about to be rewritten: The official start of a contraction will likely mark the end of an economic “recovery” during which the incomes of Americans in the middle never recovered from the last recession.

In the typical ups and downs of the American business cycle, median household income falls during recessions, then in recovery climbs back up at least to where it was before the downturn. This has been the pattern since the government began publishing data on median household income in 1967, according to John Irons, research and policy director of the Economic Policy Institute. But since the current recovery began after the 2001 recession, wages and salaries have been largely stagnant, and so have overall household incomes. “With this recovery, we’re not going to make it back to where we were before the last recession,” Irons says.

EPI analyst Jared Bernstein has noted that a typical family’s income in 2006, the last full year for which data are available, remained 1.7 percent below its 2000 peak. Wages and salaries, adjusted for inflation, fell in 2007, though the broader measure of household income won’t be available until August. Still, it hardly seems realistic to believe that incomes will suddenly spurt up now that unemployment is rising and businesses are retrenching.

The current downturn may have been touched off by the mortgage crisis or the energy-price crisis or the resulting crisis in consumer confidence. So the political system will do what it typically does — respond to these most visible crises with treatments that are most visible to voters.

Beneath the surface is the larger problem of stagnant incomes, more difficult to explain but with deeper and broader implications. What does it mean that the economy now performs so badly, for so many, that we cannot even climb back to where we were at the beginning of the decade?

For one thing, we have to give up the prevailing political aversion to stating the obvious: Unfettered trade in its current form hasn’t just hurt factory workers. It seems to be depressing incomes more broadly. Among economists, at least, “there’s a growing realization that trade hurts people who are not laid off,” Irons says. “That textile worker is going to look for work as a nurse’s aide, and then nursing wages are going to be depressed.” The old solution of retraining workers in import-battered industries, still crucial in hard-hit manufacturing towns, won’t work as a bigger economic strategy.

The mantra that education or technology skills somehow would shield white-collar Americans from the fate of blue-collar manufacturing workers is equally shopworn. Just ask one of the thousands of telecommunications and information technology workers who’ve been laid off since 2000 — or, for that matter, any of the thousands soon to be given their pink slips at Sprint.

It’s too glib to argue that for all the jobs destroyed during a slump or a longer period of economic change, new ones eventually emerge. This may be true in the abstract. But what if the new jobs don’t pay as much as the old?

In the 1980s, the political class kept assuring the working class that we were not going to become a nation of “hamburger-flippers.” We haven’t. But something else has flipped. It’s the bargain under which most workers could once rely on skills, education, experience and diligence to get ahead financially.

Six or more years of stagnating incomes can’t be called an aberration. It’s a trend, all the more abhorrent because the political system has for so long refused to even acknowledge it. We look again and again at the same discrete parts of the problem — staggering health care costs imposed on business and workers alike, for example — and overlook the fullness of the crisis.

A short-term economic stimulus package is necessary to fill some empty pockets. But it can’t fill the void created by so many years of ignoring reality.

Marie Cocco’s e-mail address is mariecocco(at)washpost.com.

© 2008, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.