I Am the Beggar of the World

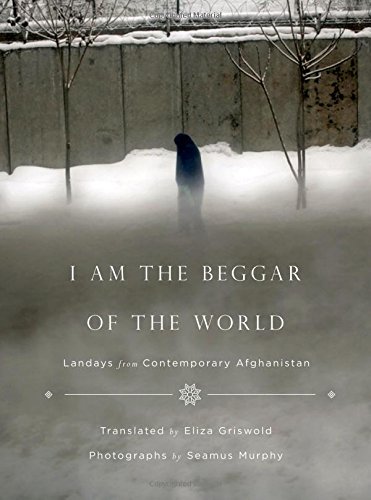

In a striking collection of underground poetry written by Afghan women—and punctuated by photographs from the women's lives—voices that are often silenced speak out about topics as varied as the Taliban, American occupation, sex, poverty, domestic abuse, marriage, Guantanamo and George W. Bush. Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

“I Am the Beggar of the World” A book edited and translated by Eliza Griswold To see long excerpts from “I Am the Beggar of the World” at Google Books, click here.

Eliza Griswold, the journalist and poet who collected, translated and edited the collection of Afghan poetry titled “I Am the Beggar of the World,” writes about the form of the poems in the book, which has its origins in an oral tradition practiced among groups of Afghan women for many years:

A landay has only a few formal properties. Each has twenty-two syllables: nine in the first line, thirteen in the second. The poem ends with the sound “ma” or “na.” Sometimes they rhyme, but more often not. In Pashto, they lilt internally from word to word in a kind of two-line lullaby that belies the sharpness of their content, which is distinctive not only for its beauty, bawdiness, and wit, but also for the piercing ability to articulate a common truth about war, separation, homeland, grief, or love. Within these five main tropes, the couplets express a collective fury, a lament, an earthy joke, a love of home, a longing for the end of separation, a call to arms, all of which frustrate any facile image of a Pashtun woman as nothing but a mute ghost beneath a blue burqa.

The word “landay,” from which the Pashtun folk poem takes its name, means “short, poisonous snake,” and in many ways the 2-line, 22 syllable poems sting like the eponymous creature, leaving a long-lasting effect with their short, biting lines. And while the Pashtun couplets are often feisty and witty, they can also be full of grief and longing — the inevitable effects of decades of war and loss.

“I Am the Beggar of the World” is beautifully punctuated with photographs taken by Seamus Murphy in Afghanistan, as well as anecdotes and commentary written by Griswold that explore the themes of the poems as well as gloss certain ideas, terms or history of which the reader may be unaware. Divided into three sections — Love, Grief/Separation and War/Homeland — the editor allows us to peek briefly into the everyday lives of Afghan women. Some of the poems are included in Pashtun as well, but not enough — the collection, which does such delicate and fine work of presenting these poems in a manner sensitive to their native culture, would benefit from being a bilingual edition to allow readers to see the beauty of the Perso-Arabic script juxtaposed with the familiar Latin letters. Moreover, it would allow those interested in reading the original the ability to do so.

Griswold was able to collect these poems during the several years she spent working as a foreign correspondent in Afghanistan, and did so at great risk to her own personal safety. But perhaps she drew some of her courage from the women who shared these landays with her and others, despite knowing that doing so could mean bodily harm or death. When the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in 2001, Griswold explains in her introduction, women were kept from leaving their homes for fear they’d be kidnapped or raped. Poetry then, and in many cases radio shows about poetry, became the only source of education for many young Afghan women. And yet the literary form is forbidden to women in many parts of the country, especially when it discusses love, because “it implies dishonor and free will.” Women have been beaten and sometimes killed when others discovered their lyrics. In one case, a poet even set herself on fire as protest against the brutality she suffered when her brothers found her poems.

Landays such as the following reveal some of the dangers and injustices many women face in Afghanistan, even at the hands of their own family members, simply because they were born female.

“You sold me to an old man, Father. May God destroy your home, I was your daughter.”

“When sisters sit together, they always praise their brothers. When brothers sit together, they sell their sisters to others.”

“In my dream, I am the president. When I awake, I am the beggar of the world.”

The title of the book, which was taken from this last landay, is an epigraph of the lives of women indentured from birth by a patriarchal culture. The perils they face in their homeland, however, are not only inflicted by the men in their society, but also, as many landays show, by foreign military forces.Such an intimate glimpse into the concerns, grief, love and anger of these women allows American readers to better understand, from across oceans, how our own country’s actions have affected the daily lives of these women, sometimes for better, but mostly for worse. The poems touch upon the legacy of the changing enemies of Afghanistan — British, Russian, American — as well as the Taliban, the enemy from within which is often met with ambivalence. The Taliban is repudiated by many for its oppressive, violent ways, but at the same time can be seen as the force that resists foreign occupation.

“May God destroy the Taliban and end their wars. They’ve made Afghan women widows and whores.”

“If the Taliban weren’t here for the world to see, these foreigners would be free to occupy every sacred country.”

These foreigners, most recently the Americans, have ruined entire villages with their violence, as can be seen in the following landays.

“May God destroy your tank and your drone, you who’ve destroyed my village, my home.”

“My Nabi was shot down by a drone. May God destroy your sons, America, you murdered my own.”

These short verses, filled with palpable anger, give a voice to grieving mothers, lovers, daughters and sisters who have lost loved ones in war after war. The image of the ever-hovering drone is particularly harrowing, echoing its “omnipresence in the skies above the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan,” as Griswold writes, able to strike anyone at any moment. The journalist explains that poems, as well as videos and hymns, that call for “death to America,” are common and often kept on smartphones “as a security measure” to prove one’s loyalties when stopped by militants, who will likely destroy a phone if it contains anything considered Western propaganda. But more than a security measure, the poems express the very real psychological anguish inflicted on Afghans by American weaponry.

George W. Bush himself has made it into the landays:

“May God destroy the White House and kill the man who sent U.S. cruise missiles to burn my homeland.”

“Bush don’t be so proud of your armored car. My remoti bomb will blow it to bits from afar.”

The president responsible for the American occupation of Afghanistan has made his way into popular folklore in precisely the way one imagines: as the person at fault for the havoc wreaked on an entire nation. In an ironic reversal, the second poem promises to use remote-control bombs (or drones) against the very man who sent them to “burn my homeland.” Even the U.S. detention center in Guantánamo Bay, in which people are held without trial and said to be tortured, has made its way into these popular poems:

“Come to Guantánamo Follow the clang of my chains.”

A mother in search of her son and grandson, who she originally believed were sent to Cuba, told this poem to Griswold. The mother asked Griswold during their encounter in Kabul why Americans didn’t ask questions about accusations, sometimes rooted in land disputes, that led them to arrest people who were often innocent. Her question is a piercing one and could be asked of all Americans involved in the Afghanistan War: What questions were asked, if any, before the nation was invaded, before thousands of lives were lost?

And although war seems present in most of the poems in the collection, there are also love poems, both tender and sensual:

“Slide your hand inside my bra. Stroke a red and ripening pomegranate of Kandahar.”

“Bright moon, for the love of God tonight Don’t blind two lovers with such naked light.”

“You’ll understand why I wear bangles when you choose the wrong bed in the dark and mine jangle.”

Poems such as these are a testament to the universal themes of erotic love as well as the pain of coming of age, lines that could speak to women from Afghanistan to America and beyond. Perhaps this is one of the most important messages of the collection — that although Afghan women’s lives vary in many ways from those of their Western counterparts, we share common experiences and emotions that should allow us to understand one another in intimate ways. Griswold gives these poems the task of bridging cultures and creating empathy. These landays then, with their piercing words, memorable images and often heartbreaking tales, bring the lives of these women into vivid detail before our eyes, an encounter that is fleshed out in photographs and in the short documentary Griswold and Murphy made for the Poetry Foundation. It is an encounter that cannot and should not be forgotten.

To read more about Griswold’s project, click here.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.