Human Population Growth Continues to Threaten Biodiversity

Scientists find that impacts of population growth on the planet’s biodiversity aren’t generally as bad as has been feared -- but are intensifying rapidly in species-rich areas.Scientists find that impacts of population growth on the planet’s biodiversity aren’t generally as bad as has been feared—but are intensifying rapidly in species-rich areas.

By Tim Radford / Climate News Network

The Congo Basin rainforest in West Africa is one of the biodiversity hot spots that face increasing pressure from human impacts. (Severin Stalder via Wikimedia Commons)

LONDON — Foresters, geographers and ecologists have some good news. Although human population growth between 1992 and 2009 was 23%, and the global economy grew by 153%, the devastation to habitats, ecosystems and wilderness increased by only 9%.

But this single ray of good cheer is countered by a bleak warning from the same scientists that threequarters of the planet’s land surface is experiencing measurable human pressures.

And although the scientists found that the “footprint” of humanity has not grown to the same scale as the mass of humans and their goods and chattels, they report in Nature Communications that “pressures are perversely intense, widespread and rapidly intensifying in places with high biodiversity”.

The study’s lead author, Oscar Venter, a forest scientist at the University of Northern British Columbia, says: “Seeing that our impacts expanded at a rate that is slower than the rate of economic and population growth is encouraging. It means we are becoming more efficient in how we use natural resources.”

Pioneering study

The “human footprint” is ecologists’ shorthand for the impact humanity makes on the natural world — the growth of towns and cities, mines, smelting works, power stations, and the conversion of what would once have been savannah, wetland or forest.

The first pioneering study of the human footprint was based on data from the 1990s and published in 2002. Dr Venter and his colleagues looked at data for the built environment, roads, crops, pasture, night lighting, railways, navigable waterways and human population density to measure the subsequent pattern of impact.

In 1993, there were areas of no measurable human footprint over 27% of the continents, other than the Antarctic. In the subsequent decades, humans encroached onto 23 million square kilometres of these once-empty plains and forests.

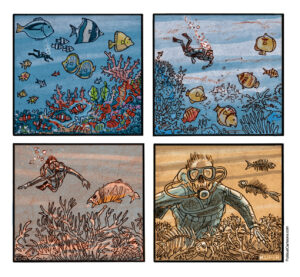

“Our maps show that 97% of

the most species-rich places on Earth

have been seriously altered.”

The remaining pressure-free lands, the researchers write, are in the boreal and tundra regions, the Sahara, Gobi and Australian deserts, and the remote moist forests of the Congo and Amazon basins.

Worryingly, regions with the highest biodiversity were also associated with the highest levels of human pressure.

The scientists zeroed in on the detail, and examined 772 “ecoregions” — including Canadian aspen forests, peninsular Malaysian montaine rainforest, Belizean pine forest, Baffin coastal tundra, and New Guinea mangroves — in the map of natural terrestrial habitats.

Only 3% of these registered a decline in human pressure, which increased by more than 20% in 71% of the rest,

“Our maps show that threequarters of the planet is now significantly altered and 97% of the most species-rich places on Earth have been seriously altered,” says James Watson, an ecologist at the University of Queensland, Australia.

Booming economies

The researchers had expected that nations with booming economies would also reveal expanding environmental impacts, but this wasn’t always so.

Eric Sanderson, senior conservation zoologist of the Wildlife Conservation Society, who led the original 2002 Human Footprint Study, says: “It is encouraging that countries with good governance structures and higher rates of urbanisation actually grew economically while slightly shrinking their environmental impacts of land use and infrastructure.

“These results held even after we controlled for the effects of international trade, indicating that these countries have managed in some small measure to decouple economic growth from environmental impacts.”

The study is timed to coincide with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s world congress in Hawaii next month, and the maps and data are intended as guides for researchers and policymakers who must make decisions about the protection of wildlife reserves and natural habitats.

The challenge, says Dr Venter, is to make development sustainable. “Concentrate people in towns and cities so their housing and infrastructure needs are not spread across the wider landscape,” he advises, “and promote honest governments that are capable of managing environmental impacts.”

Tim Radford, a founding editor of Climate News Network, worked for The Guardian for 32 years, for most of that time as science editor. He has been covering climate change since 1988.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.