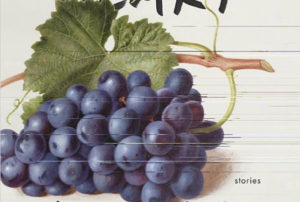

Fortune Smiles

The stories in Adam Johnson’s new collection are all set in an uncanny world you recognize but don't. From ravaged American cities to abandoned torture chambers, each one is a miniature demonstration of why Johnson won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Random House

Random House

Random House

|

To see long excerpts from “Fortune Smiles” at Google Books, click here. |

“Fortune Smiles” A book by Adam Johnson

The six stories in Adam Johnson’s new collection, “Fortune Smiles,” will worm into your mind and ruin your balance for a few days. From ravaged American cities to abandoned torture chambers, these pieces take place in an uncanny world you recognize but don’t. They’re all cast in an unsettling twilight of moral struggle, and each one is a miniature demonstration of why his remarkable novel “The Orphan Master’s Son” won the 2013 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

In fact, the title story, placed last in this collection, returns to the setting of “The Orphan Master’s Son.” Two recent defectors from North Korea, DJ and Sun-ho, are struggling to assimilate in the opulence of Seoul. Crooks raised in the gray horrors of the Dear Leader’s paradise, they find the people and technology of their new home otherworldly: “Passing a fitness center, DJ stared at rows of men running on treadmills,” Johnson writes. “What force was driving them? What were they running from? Next came a cat cafe and a parlor where teenage girls danced with machines. At an empty shopping plaza, he watched an escalator endlessly cycle, the steps appearing, rising, and disappearing as it carried no one up to nowhere.”

DJ’s innocent perspective on our technology-infused world exposes the weirdness we live with so easily. But it’s the loneliness that wears on these defectors most. Sun-ho, in particular, finds life in the free South intolerable, though he knows, firsthand, that “the North was a land of thuggery, corruption, brutality and murder.” “What happened to our country?” he asks. “How did this happen to us?” It’s a question that finally drives him to an act that’s strangely lovely — but also ridiculous and deadly.

Johnson’s style is quiet and unassuming, a gentle reflection of the muted people he usually writes about. But restraint only increases the intensity of these stories and makes their visceral effect more surprising. His characters are cramped by circumstance or weakness, struggling to make sense of situations they can’t entirely understand or even believe.

That sense of bewilderment explodes in “Dark Meadow,” a deeply disturbing story about a reformed kiddie-porn addict. “You have to understand,” the narrator pleads, “that I have never hurt anyone in my life and that I am the one who gets wounded in this story.” Still struggling decades later to recover from being raped, the narrator now works in computer security, where he sometimes does jobs for pornographers and — secretly — makes their illegal photos easier to trace. The story’s terror stems from the way this man teeters precariously between monster and victim. He is, in many ways, the most affectionate, most responsible character in the story, but he hangs over a precipice of violent depravity.

Technology snakes through all these pieces, in ways that remind us just how transformative the last few years have been — and how increasingly creepy the future will be. “Nirvana,” set just a few years off, takes place in Palo Alto, Calif., that techno-paradise that promises to answer all the soul’s desires electronically. The narrator is a brilliant programmer nursing his wife through a terrifying neurological condition she may not survive. To comfort her, he develops an interactive virtual replica of the recently assassinated U.S. president that can converse using clips from a database of inspirational speeches and public appearances. Hearing these conversations — plaintive questions on one side, a Reaganesque holograph on the other — is bizarrely funny and desperately sad.

Those incongruous tones clash even more violently in “Interesting Facts,” another story about a marriage tested by illness. But this time, the narrator is the embittered wife of a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist who writes about North Korea. Battling breast cancer, she keeps torturing herself and her husband by asking how long he’ll wait to date after she dies. Even if you don’t know the autobiographical context (Johnson’s wife is a breast cancer survivor), the story’s aggrieved, increasingly furious voice will haunt you.

Half these stories were published previously in Tin House, a Portland, Ore., journal, with a whopping 3,500 subscribers, which illustrates how important — and precarious — the tiny tributaries of literary fiction are.

The only piece that hasn’t appeared previously is “George Orwell Was a Friend of Mine,” a masterful story about a retired, unrepentant East German official who worked in the Hohenschonhausen Prison. Still living near the notorious facility, which is now a museum, he spends lonely days walking his little dog and mocking the tour guides — former prisoners — who escort tourists and students through the gates. It is, by turns, cringe-inducing and infuriating. And with its shocking conclusion, it delivers a harrowing portrayal of the way years of denial can twist the mind.

“George Orwell Was a Friend of Mine” will be published separately in December by 21st Editions in a limited run of 37 handmade copies for $9,000 each. That’s just one more reason to consider this collection of six astonishing stories a bargain at $27.

Ron Charles is the editor of The Washington Post’s Book World.

©2015, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.