Sour Hearts

In Jenny Zhang’s debut collection of short stories, characters are filled with battle scars whose origins remain invisible. Random House

Random House

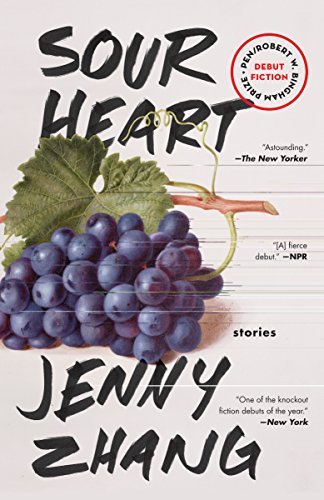

“Sour Heart: Stories” A book by Jenny Zhang

It’s easy to see why Lena Dunham chose to publish Jenny Zhang’s compelling and wildly original debut book of loosely connected short stories at her new Lenny Books imprint at Random House. At first glance, Dunham and Zhang seem to be from different worlds, but there is much that binds them. Dunham grew up a rich kid, the daughter of artists, and attended private school in Manhattan. Zhang grew up the resilient daughter of impoverished and traumatized Chinese-American immigrants who came to America with high hopes that were quickly demolished. Yet the women seem similar in temperament: They are irreverent, defiant and drawn to the hipsters and outlaws who linger at the fringes of our society. Both seem comfortable walking a high wire and channel their creative passion into their writing, which often reveals uncomfortable truths.

Zhang, a beautiful young woman with long black hair, bright eyes and a nervous smile, has spoken and written about the difficulties of her childhood. Zhang’s father left her and her mother in Shanghai when Zhang was only 3 to study linguistics at NYU. Her mother left a year later to join her father. She reunited with them both at 5; the scars from their separation still resonate. Her father dropped out of his Ph.D. program at NYU shortly before he was going to present his dissertation, and got a computer science degree from a local community college. He was already in his late 30s. Zhang realizes that her parents are both survivors from the brutal aftermath of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. They endured three decades of a genocidal demagogue whose “promise of socialism was a promise of fascism.” Many of her parents’ relatives in China were tortured and maimed; some committed suicide.

Click here to see long excerpts from “Sour Heart” at Google Books.

Zhang, while still a toddler, told her first stories into a cassette player. When she was older, she knew she wanted to become a writer. Her fiction often speaks to the sense of “otherness” she feels living in America. She explains that not a day goes by when someone does not make a denigrating gesture or comment about her ethnicity as she walks down the street. Sometimes the racism is hidden behind humor. She attended a concert years ago while studying at Iowa’s fiction workshop where she was accosted by three antagonistic girls demanding to know whether she was Japanese, Korean or Chinese. She tried to move away from them as their laughter rang in her ears. When she shared this experience with her mostly white classmates, she was disappointed with their disingenuous expressions of empathy.

Zhang never had a mentor. If she could have had one, she says she would have liked it to have been bell hooks. She spent much of her young life trying to cope with the discomforting feeling of not belonging, being outside the mainstream culture. This feeling was present at Stanford where she got her degree, in the mountains of Romania where she taught English, and noticeable even in San Francisco, where she worked as a union organizer for Chinese home-care workers.

When she told her parents she wanted to become a writer, they harshly discouraged her and told her she would fail. In recent years however, her poetry, first-person narratives and short stories began to get noticed. Readers were struck by the forcefulness and inventiveness of her prose. Zhang has the capacity to sound both distant and present; her narrative voice is simultaneously filled with an urgency and immediacy, and yet it is spoken from the perspective of someone looking back at their past.

The stories in “Sour Heart” are merciless in their depictions of childhood pain and loneliness. They chronicle the lives of Chinese-American immigrants who are living amid brutal poverty and frequent relocations in New York City during the 1990s. Her narrators are all unique, but in some ways they feel and sound the same. They are young girls or teenage daughters trying to make sense of perpetual chaos. The fathers in these stories are usually absent, lost to studying and delivering Chinese food all night for a pittance. They often cheat on their wives and emotionally abuse them. The mothers are broken women who often turn on their daughters, using them as receptacles for their angst. Little affection or tenderness is shown by anyone. The mothers are controlling, dismissive, demanding, combative or unreliable, and the daughters are left trying to decode the dysfunction that lies before them. Boundaries are often transgressed, resentments overflow and violence sometimes erupts. These are broken families who often turn on one another in despair.

In the opening story, “We Love You Crispina,” set in 1992, we learn about a 9-year-old girl’s life in Bushwick, Brooklyn, living in an apartment nestled between two crack houses. The family is forced to use the Amoco gas station’s bathroom across the street since their toilet never works. The neighbors, immigrants from Martinique and Trinidad, taunt the little girl when she walks home from school, shouting, “Yo, it’s the rape of Nanking! It’s really the rape of Nanking!” The girl is taken with her mother’s beauty, particularly her hair, describing how “her hair was so straight and long and fell down her back like heavy curtains and she had skin so white it reminded me of vanilla ice cream.” But she remembers knowing even then that beneath her mother’s exquisiteness lay a broken woman. She remembers how much pressure she always felt to excel and make something of her life, yet she knew, too, that if she did succeed, it would mean leaving her mother — something she felt she would never be ready to do. But as she grows older, resentments start to fester. She resents being told how much her parents do for her. She can’t stand the loneliness of the apartment when they are both at work. She suffers from a constant itchiness that is intolerable, an itchiness so harrowing her parents both have to scratch her to sleep at night. They send her back to China screaming, realizing they can’t care for her; she goes and returns years later. There remains a wall between them that never comes down, though they pretend it has.

In “The Empty the Empty the Empty,” another Chinese girl thinks obsessively about her mother’s resentment toward her. Her mother has time for friends and neighbors — everyone else but her. The mother continually chastises the little girl for being selfish and ungrateful. The child knows what her mother wants her to say and sometimes practices the speech in her own mind: “ ‘I’m sorry,’ I said in my head, all the time, but never in real life, just like my mother who never said I’m sorry to me in real life either, only I had no idea if she apologized in her head, and if she realized she had the power to hurt me, to disappoint me as much as I disappointed her, to make me feel so alone that sometimes I couldn’t recognize myself in front of mirrors or in pictures.” But the little girl refuses to say these words aloud to her mother. Perhaps succumbing to her mother’s pressure would destroy what was left of her. Instead, she remains defiant and begins to think about other places where she could find people who really love her.

In “The Evolution of My Brother,” Zhang explores an intense relationship between an older sister and a younger brother. The daughter hates the way her mother treats her brother, often force-feeding him when he refuses to eat. When the mother leaves home, the daughter tries to soothe him, and he follows her constantly, lost without her support. When the daughter leaves for college and comes home, her brother seems no longer to need her as he once did. Her parents are still busy and ignore her. She spent years dreaming of escaping them, but now is crushed to find they seem not to notice her. She is finding college hard, and figuring out who she is even harder; she is seeking comfort but doesn’t quite know where to turn. She thinks, “How strange it is to return to a place where my childish notions of freedom are everywhere to be found — in my journals and my doodles and the corners of my room where I sat fuming for hours, counting down the days when I could leave this place and start my real life. …” Freedom is not living up to her expectations.

In one of the most magical stories, “Our Mothers Before Them,” the narrative bounces back and forth in time. It starts in 1966, describing the world in which one little Chinese girl’s parents grew up: “Schools had been indefinitely shut down for a month and the children of Shanghai came out in packs to play, the first month of no schools and no responsibilities had spilled feral energy into the streets. Hardly anyone spoke of poetry anymore unless it was coded in another kind of poetry. It was dangerous to be precious about the lakes and the summer willows that had been fetishized by the old masters: now it either served the revolution or it was an act of sabotage. Beauty was a distraction, it was an indulgence, and all the things that carried it, all its vessels, were to be burned.” The story lurches forward to 1996 and the 8-year-old girl is thinking how much she loves it when her brother braids her hair since it makes her “feel moon-blue-stone like my favorite crayon color, and feeling that way made me fearless against the nightmares I knew I would have.” The little girl’s mother is excited because her brother is coming to visit from China before studying at an American university. Her mother has always been a sad and badly damaged woman. She wants the little girl to tell her uncle when he arrives that she loves her mother more than anyone else — something the little girl doesn’t want to do. The little girl finds her mother inaccessible and has studied her remoteness for years, explaining, “One of the reasons I studied her so closely was because I wanted to track how she ended up in those secret places I couldn’t enter. How did she get there and why couldn’t I follow her. But it was no use. She frequently disappeared without warning and I had to tell myself that if I wasn’t part of it, then I wasn’t part of it, and I would learn to savor that, too.”

Zhang’s stories show us what happens when relationships between mothers and daughters die. We watch the daughters learn that their mothers are unavailable, not to be trusted, or worse. We watch them scramble for solace, sometimes to dangerous places. Zhang knows and has said that the most tragic thing about most of us is what people can’t see. Her characters are filled with battle scars whose origins remain invisible. No one wins in these stories, neither the mothers nor the daughters. Zhang refuses to look away and shows us how doors shut. How trust becomes eroded. How the ability to embrace one another again, at some point, is lost forever.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.