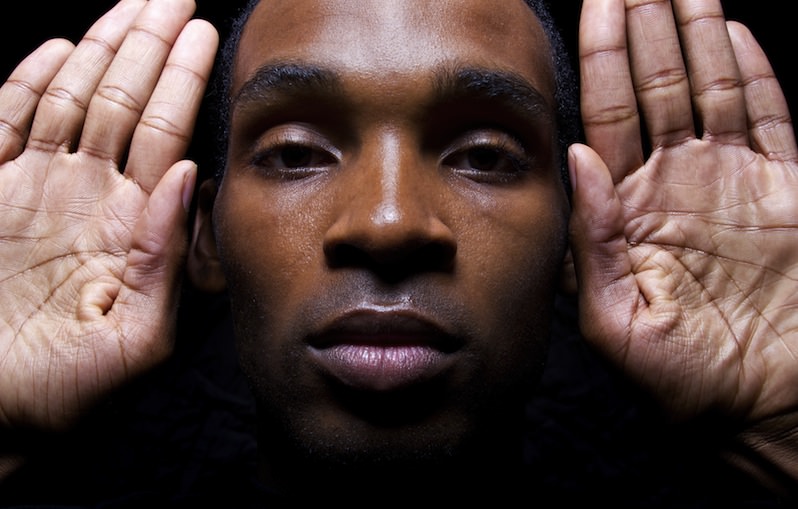

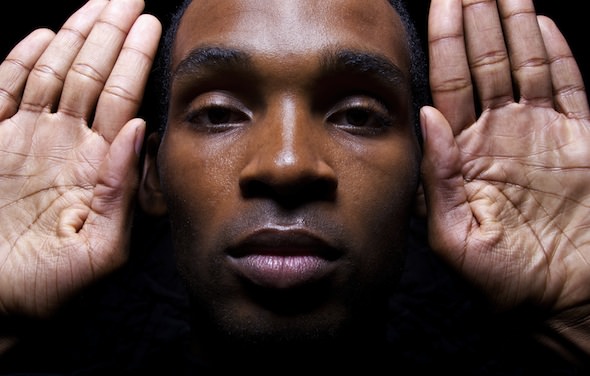

For Black Men in America, There Is No Break From Racism

The events of this summer in Ferguson, Mo., highlighted an ugly truth to mainstream Americans: Black men in this country are viewed as so suspicious by law enforcement that they are often shot first and questioned later.

The events of this summer in Ferguson, Mo., highlighted an ugly truth to mainstream Americans: Black men in this country are viewed as so suspicious by law enforcement that they are often shot first and questioned later. It is a reality that black men have been living with in the United States since the very beginning.

As of 2010, black American men had the shortest life expectancy of any demographic in the U.S. In their interactions with law enforcement African-Americans are three times more likely than whites to have their person or vehicle be searched, more than three times more likely to be handcuffed and almost three times more likely to be arrested. One in every 15 African-American men is incarcerated compared with one in every 106 white men. Fully one-third of all black men can expect to go to prison during their lifetime. In 2009-2010, black male students graduated at the rate of only 52 percent nationwide compared with 78 percent for white males.

There are many more statistics, each as dismal as the other. So much so that President Obama recently launched a project called My Brother’s Keeper in order “to address persistent opportunity gaps faced by boys and young men of color and ensure that all young people can reach their full potential.” Why do we as a society refuse to embrace the humanity of black men? Why are black men constantly seen as “the other”? How does it affect their psyche, and by extension, all of ours?

I wanted to explore these questions, and in a series of conversations with black men in my own circle of friends I found that not only did every single man I spoke with have numerous stories to share about brushes with law enforcement but that such incidents were a relentless and debilitating part of daily life in a way that nonblack Americans simply do not have to contend with.

Jon (I will use only first names here), is a 46-year-old man of average height, lean build and dark chocolate skin. His father worked as a janitor and his mother as a cafeteria manager. Jon’s parents often argued, primarily because money was tight. When he was a little boy he loved Superman because “it’s a real easy thing when you’re growing up in a difficult situation to see the escape value of superheroes.” To this day Jon loves comic books and science fiction. He works as a network administrator in a media organization. Jon is full of energy, running around his office solving one problem after another in rapid succession, a smile and a joke constantly on the tip of his tongue.

As an adult, Jon senses the nervous glances of people constantly. Practically every person of color in the U.S. has had the experience of being eyed by sales clerks in stores. Even President Barack Obama has mentioned his experience of “shopping while black.” Jon told me that being viewed with suspicion in stores is an experience that “never goes away.”

They never stop following you, even if you get a little gray hair, you get older, you dress differently — it doesn’t matter. You buy stuff in that store every day, it doesn’t go away. They don’t want you there, their customers don’t want you there … I can’t imagine walking into a store without that feeling. It would be great. To have to walk into any store and to feel like people in there are going to think that you’re going to steal something. And you’ve never stolen anything in your life. And we’re never supposed to be angry about it.

Beyond the nervous sales clerks is the real and present danger from armed police officers. I asked Jon to share some of his brushes with law enforcement and he responded, “There are just so many. Those really aren’t our stories. That’s just the norm; that’s how it is.” He related a story from when he was 21 years old and asked out a white female friend on a date. The two of them drove to Malibu beach on Valentine’s Day. During the course of their date and their drive home, they were stopped on three occasions by police for no other apparent reason than to make sure Jon was not harming his white date. It didn’t matter that she was carrying a small amount of marijuana on her person — the police were simply not interested in that.

On another occasion, when Jon briefly worked in a parking lot as a product vendor, he was arrested on his first day. Then, two days later, he was surrounded by five police cars, from which about 10 cops emerged with their weapons pointed at him and questioned him about a 9 mm gun. Apparently Jon “looked just like a guy who had robbed someone.” He told me, “I have looked just like a guy that robbed a convenience store [so many times]. … I’ve had my arms twisted behind me and slammed into a police car just for walking down the street, and repeatedly been asked ‘where do you belong?’ “

Jon’s experience was strikingly similar to that of Mark, another friend who shared his stories with me. A tall, eye-catching man with light brown skin, Mark is 48 years old and sports dramatically long hair, which he told me was the result of “a conscious decision.” “My hair,” he said with a smile, “is black-people hair,” and he wears it “as part of my identity.” Soft-spoken and thoughtful, Mark is most comfortable in front of a computer, editing audio files as part of his job. He is also a J.R.R. Tolkien geek, a lover of jazz music, the host of a jazz radio show, a highly skilled DJ and a practitioner of Capoeira, a form of Brazilian martial arts. Mark learned very early on that being black meant that the police would treat you with far more suspicion than your white friends. He related a story from his childhood, when he and a Korean friend were arrested in their neighborhood at the age of 14 for having a pair of homemade nunchucks they had been playing with. Mark’s white friends, who were also in the vicinity at the time, were left alone. “If I was white,” Mark speculated, the police “would have given a warning. They would have taken [the nunchucks], maybe asked ‘are your parents home?’ and that would have been the end of it.” That experience with the police was not Mark’s first — nor his last.

One evening while driving home with a black friend, Mark recounted being pulled over by the police. “We knew the drill,” he said. “I automatically put my hands on the steering wheel where they can see them. I don’t talk back. I’m very personable. I know the deal, because I’m not trying to leave this planet early.” It was a tiny infraction that involved a problem with the car’s license plate. “They handcuffed us on a busy part of the street, right near where my neighbors can see,” said Mark, shaking his head. “We weren’t resisting or anything. Still, they felt the need to put us in a humiliating position.”

A third friend I spoke with is a 43-year-old master gardener and environmentalist named Hop. Friendly and easygoing, Hop defies the stereotype of black Americans in that he loves the outdoors and is most comfortable camping, hiking and gardening. He is bearded, with deep, dark skin, athletic, a vegan, a chicken farmer and a father of two. Those whom he counts as friends are always met with bear hugs and kisses.

To get to his work as a consultant in urban agriculture, Hop bikes from and to home. In fact, he has been biking for 15 years in three cities: Seattle, Portland, Ore., and Los Angeles. But in all three cities, his experience with police has been uncannily similar. He is routinely stopped by officers and gets asked questions such as “What are you doing? Where’d you get that bike from?” and even “You don’t look like you can afford that bike.” Like Jon, Hop also often gets accused of resembling a suspected burglar.

Hop recalled being questioned aggressively by undercover police officers while in his own yard gardening early one morning. He told me, “In my hand I had a garden trowel and I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m going to get shot to death in my backyard while I’m trying to garden.’ “

Hop has been confronted by police so often that he has lost count. “On many of the occasions that I’ve been stopped by law enforcement, it has been at the point of a gun,” he said. Hop added soberly that during those moments “I’ve felt that it could be over. And then there I am on the 6 o’clock news.”

A constant fear that black parents like Hop and Mark have to contend with is the threat of having their children taken away from them. Hop faced such a terrifying scenario when one of his daughters strayed away from her parents while at a store. It turned out she had managed to leave the store and was attempting to come back in when Hop went to retrieve her, but by then someone had apparently already called the police. The officer told Hop, “With the stroke of a pen I could have the Department of Health and Social Services here and you won’t see your kids.” Hop’s wife, a Salvadoran-American lawyer, was also present, and Hop believed that “the cops were being very disrespectful to both of us.”

In speaking for just short amounts of time to only three of my black male friends, I was made aware of so many experiences of humiliation that I can conclude only that there is likely not a single African-American man alive today who has not been unfairly singled out by ordinary people or the police consistently throughout his life. Hop shared how constant a struggle it is, saying:

One of the impacts of racism on people, particularly black men, is that it is a hurdle, it is a barrier, it is a wall to actually living our most authentic life, who we actually would like to be. So much of this that happens, we’re steeped in it, we breathe it, we live in it, we’re like fish in it, it’s all around us. It’s always on our mind.

All three men linked the persistence of racism to the fact that American society has never recovered from the horrors of slavery and the Jim Crow segregation that followed. From Emmett Till to Michael Brown, the fear of black masculinity has remained part of the American psyche and may be at the root of anti-black prejudice and oppression. Mark agreed that racism has its basis in “unresolved issues about how the country started. It goes back to the roots of the country. Slavery is such a deep offense to life. Period. And they know, the oppressors know what they did. I think that stays in the psyche, in the background.”

Hop concurred, saying, “when slavery ended, there was no therapy, there was no counseling, for black people, or for white people, because white people are still crazy after all that stuff. We are all still burdened by that.”

Ultimately Jon saw the struggle to overcome racism in the U.S. as a matter of convincing society of the basic humanity of black men. He told me a story of how he learned about slavery as a young child in Catholic school. “All slave owners had to be evil, right?” he asked his teacher, a nun. That didn’t seem to be such a stretch, he thought. “And instantly [the nun said], ‘No, of course not! They just didn’t understand that you were all people.’

“And so maybe that’s what we’re all trying to do,” Jon said with a shrug. “We’re trying to prove that we’re people.”

In Part 2 of 2, I explore the impact that racism has had on black men’s mental health and well-being through my conversations with Jon, Mark and Hop. Read that article here.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.