Exposing the Whitewashed ‘Fable’ of the Civil Rights Movement

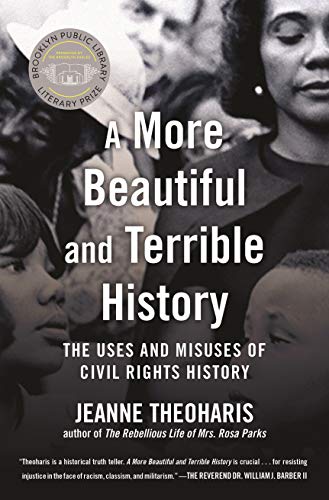

A new book argues that the memorialization of the movement becomes "a veil to obscure enduring racial inequality, a tool to chastise contemporary protest, and a shield to charges of indifference and inaction." Beacon Press

Beacon Press

“A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History”

A book by Jeanne Theoharis

“A More Beautiful and Terrible History” is a critique of what its author derides as the ascendant fable of the civil rights movement—the black protests that challenged the racial status quo between the 1950s and the 1970s. Brooklyn College professor Jeanne Theoharis contends that influential shapers of public memory have attempted with considerable success to whitewash and truncate recollections of the movement. The culprits include academics, journalists and politicians. What they have done, she charges, is depict a movement devoid of unsettling militance, with narrow aims that were accomplished on account of an attentive citizenry that only needed to glimpse injustice in order to respond nobly. The fable, she argues, is complacently triumphalist, offering a distorted mirror that misleadingly celebrates observers.

She makes her argument tellingly, offering example after revealing example. She notes, for instance, the trajectory of President Ronald Reagan’s stance toward the most prominent episode of civil rights movement iconography—the creation of a national holiday honoring Martin Luther King Jr. Initially Reagan opposed the King holiday. Then, when pressure for it became overwhelming, he adopted a strategy of co-optation. When he signed the King holiday legislation, he asserted that “we can take pride in the knowledge that we Americans recognized a grave injustice and took action to correct it”—as if King’s aspirations had been attained. She notes a troublingly similar exaggerated sunniness in Barack Obama’s remarks, starting with his campaign for the presidency in 2007, when he declared at the historic Brown Chapel in Selma, Alabama, that the movement generation “took us 90 percent of the way there”—a perceived propinquity to the racial promised land that Theoharis rightly finds preposterous.

Click here to read long excerpts from “A More Beautiful and Terrible History” at Google Books.

Even those specifically charged with educating the public about King’s life have repeatedly avoided the very forthrightness that is part of what made him so outstanding. Objecting to various aspects of the King memorial in Washington, Theoharis notes that “fourteen quotes are inscribed on it. Not one of them uses the word ‘racism’ or ‘segregation’ or ‘racial inequality.’ Not one.”

Noting that President Trump gave a piece of granite from the King memorial to Pope Francis, Theoharis asserts that such homages do little to productively honor the memory of the movement. To the contrary, “these often bipartisan acts of memorialization whitewash the history … becoming a veil to obscure enduring racial inequality, a tool to chastise contemporary protest, and a shield to charges of indifference and inaction.”

Repeatedly, Theoharis reveals facts or recollects statements that are instructive, albeit painful to consider. Emphasizing the extent to which King was disparaged while alive, she notes that in 1966 a Gallup poll found that 72 percent of white Americans had an unfavorable opinion of the civil rights leader. Stressing the extent to which political authorities in the 1960s denied the obvious reality of deep and pervasive societal racism, she quotes Gov. Edmund Brown declaring in 1965 (just as the Watts section of Los Angeles was literally going up in smoke) that “California is a state where there is no racial discrimination.” Insisting that racial prejudice was a nationwide malady and not a pathology limited to the Jim Crow South, she quotes William O’Connor, the incoming head of the Boston School Committee. “We have no inferior education in our schools,” O’Connor declared, abjuring any suggestion that evident racial biases and unfair allocations of resources had anything to do with glaring differences in the educational milieus experienced by white and black pupils in the public schools. “What we’ve been getting is an inferior type of student,” by which he meant, of course, inferior black students.

Theoharis’ systematic debunking is a useful antidote to sentimental narratives that are, as she persuasively argues, all too smug, all too easy, all too lacking in the conflict and dread, tragedy and defeat that suffused the most consequential American reform effort of the 20th century.

But Theoharis’ account is also problematic. Ideological rigidities prevent it from illuminating more fully the messy complexity of the movement’s history, legacy and lessons. She denounces wholesale internal culturalist explanations for African-American difficulties, as if such diagnoses are in principle erroneous and reactionary. Yet in the deservedly iconic “Letter From Birmingham City Jail,” one encounters King sternly lecturing complacent “Negroes who, as a result of long years of oppression, have been so completely drained of self-regard and a sense of ‘somebodiness’ that they have adjusted to segregation.” Was King, too, guilty of the “polite racism” that Theoharis attributes to others who highlight the significance of cultural and psychological maladaptations to external challenges?

Theoharis implicitly urges students of the second reconstruction to review it anew, unbound by inherited inhibitions. But with respect to certain subjects, she is conspicuously silent. She keeps to herself, for instance, whether she believes that her heroes in the Black Power wing of the movement ever committed any strategic or moral errors. Decrying the derogatory reputation that burdens the memory of the Black Panther Party, she maintains that it ought to get credit for wholesome but frequently overlooked initiatives such as its provision of medical care and free breakfast programs for children. Given her demand for realism, one might have thought that she would also confront the fact that the Black Panthers repeatedly referred to police as “pigs” and discuss what lessons ought to be drawn from the consequences of the Panthers’ rhetorical strategies.

Theoharis rails against conservative and liberal depictions of the civil rights movement and in the course of doing so offers many useful criticisms. One wonders, though, whether she fundamentally opposes mythologizing or merely the mythologizing of intellectuals to her ideological right. She observes that the “recounting of national histories is never separate from present-day politics.” Does she mean that all histories are thus merely projections of present-day politics? I hope not. But the way she advances her argument sometimes suggests a conflation of historical analysis with political exhortation. I wish that she would heed her own call for realism. Responding appropriately would mean upending fables of all sorts.

Randall Kennedy is the Michael R. Klein professor of law at Harvard Law School.

©2018 Washington Post Book World

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.