Do the Bundys Signal the End of the Great American West?

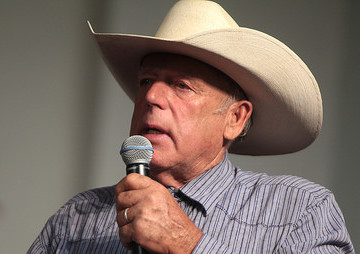

When public land is transferred to states, significant portions end up being sold off to private interests—and that means less wild nature for all Americans to enjoy. Nevada rancher and public lands scofflaw Cliven Bundy leads the contemporary attack on public land ownership. (Gage Skidmore / CC BY-SA 2.0)

1

2

3

Nevada rancher and public lands scofflaw Cliven Bundy leads the contemporary attack on public land ownership. (Gage Skidmore / CC BY-SA 2.0)

1

2

3

In essence, they are our national commons, our shared resource, not just for material goods, like timber, clean water, and minerals, but for recreation and inspiration. Seventy percent of all hunters are said to use public lands, and the percentages of birders, campers, hikers, and other recreationists must be at least as high. Public lands also help buffer us against the uncertainties of the future. Only public lands, for instance, spread unbroken over great enough distances to offer the connectedness that many plants and animals will require to adapt, to the extent possible, to a warming climate. Moreover, as the struggle to wean the economy away from fossil fuels continues, only public lands, with their unified federal ownership, are susceptible to the kind of sweeping shift in national energy policy necessary to “keep it in the ground.”

For all these reasons, the future of the nation’s 640 million acres of public lands deserves a more prominent place in our national discourse. The patterns of the past, emphasizing extractive, industrial uses of those lands, have long been in decline. An alternate path focused on restoration and biodiversity conservation has instead steadily gained traction, and indeed, its priorities — which include making room for endangered species — have inspired many of the objections of the Malheur occupiers.

Two things are certain: when large acreages of public domain are transferred to the states, significant portions of them end up being sold off to private interests. That creates a new kind of inequality that, in the natural world, parallels this era’s growing economic gap between rich and poor. It is an inequality of access to big, wild lands and to the ineffable something that Wyoming writer Gretel Ehrlich called the “solace of open spaces” and Pulitzer-winning novelist Wallace Stegner termed “the native home of hope.”

Thanks to the great western commons, which the Bundys and their legislative champions would like to dismantle, all Americans still enjoy the freedom to roam on some of the most spectacular lands on the planet. That access and that connection have been part of the American experience from Plymouth Rock through the westward migration to the present day. It is part of what makes us Americans.

The Depression-era folksinger Woody Guthrie understood the issues attending the privatization of common land. He offered his opinion of them in the least sung verse of his most famous song:

“There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me

Sign was painted, said: “Private Property”

But on the back side it didn’t say nothing —

This land was made for you and me.”

William deBuys, a TomDispatch regular, is the author of eight books, the most recent of which is The Last Unicorn: A Search for One of Earth’s Rarest Creatures. He has written extensively on water, drought, and climate in the West, including A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest. Based in New Mexico, he has managed ranches and devised cooperative grazing programs involving both ranchers and government land managers.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Nick Turse’s Next Time They’ll Come to Count the Dead, and Tom Engelhardt’s latest book, Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.

Copyright 2016 William deBuys Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.