David McReynolds, Pacifist and Socialist, 1929-2018

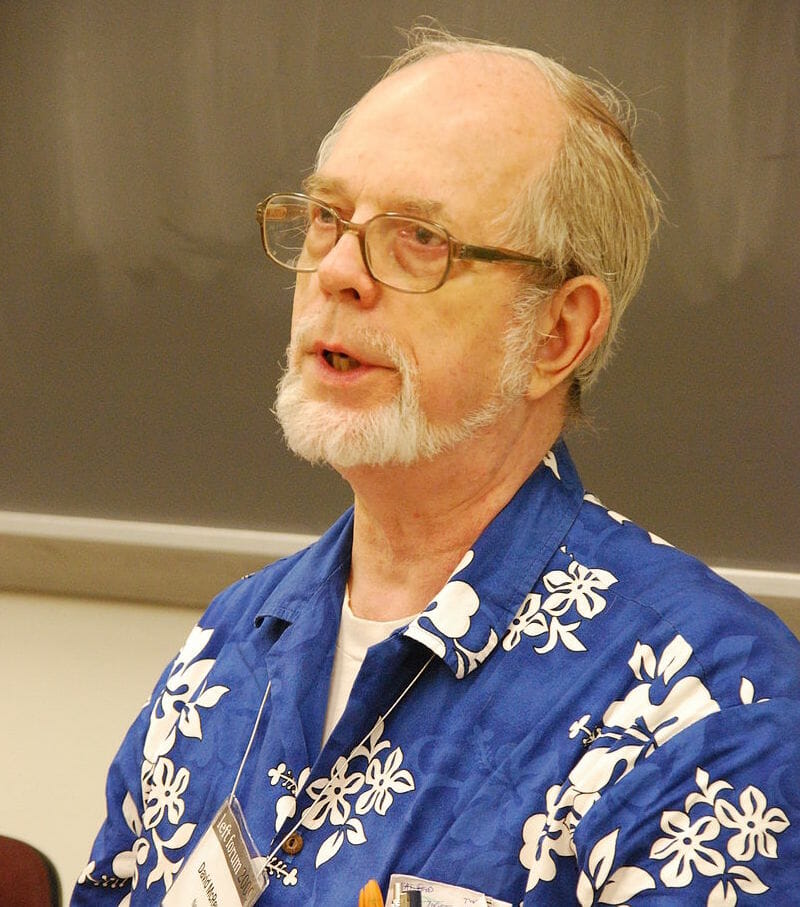

Charming, ornery, all too human: the radical legacy of a democratic socialist. David McReynolds speaks at the 2009 Left Forum in New York City. (Thomas Good / Wikimedia Commons)(CC BY-SA 3.0)

David McReynolds speaks at the 2009 Left Forum in New York City. (Thomas Good / Wikimedia Commons)(CC BY-SA 3.0)

David McReynolds was born in Los Angeles during the week of the stock market crash of 1929, a signal event in the Great Depression that would follow. His father was a devout Christian, who McReynolds thought would have been happier as a minister. Instead, McReynolds’ father became a salesman, and the toll this job took on the family was one reason McReynolds became a socialist. He thought we all deserve more happiness in our working lives, but that this would only be possible under a truly social economy.

McReynolds died this month after suffering a fall in his small New York City apartment, where he was discovered unconscious and badly dehydrated. His apartment was such a warren of books and files, piled up on the furniture, that he often moved them into the bathtub so his guests could be seated. His disorderly papers deserve an orderly archive, and this effort is underway.

McReynolds was charming, ornery, all too human. He had a gift for conciliation and attempted to draw the democratic left toward greater unity, though he also joined in the polemical arguments of his time. The grudges he held tended to be political, not personal, and he paid the price of his honesty to the end of his life. He had requested the songs of Bessie Smith and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony for his memorial, musical bookends for any remembrances between.

McReynolds grew up in a conservative Baptist family, and his first political venture was becoming a member of a traveling youth team of the Prohibition Party. After the youth division was expelled for being “Communist,” McReynolds really did turn toward the free thinking and democratic left. By 1951, enrolled at UCLA, he found the Los Angeles branch of the Socialist Party, whose members were among the bohemian precursors of the later Beats. These bohemian left-wingers, who were mostly straight, valued their gay comrades. Together, they tried adding a plank to the party’s platform that would have supported decriminalizing homosexuality and ending discrimination against gay people. A decent effort in the deepening deep freeze of the Cold War, and even courageous, given the organized campaigns to purge Reds and queers from the State Department and other government agencies in the McCarthy era. Former U.S. Sen. Alan K. Simpson, an old-school gentleman on the moderate wing of the Republican Party (a species now nearly extinct), has written: “The so-called ‘Red Scare’ has been the main focus of most historians of that period of time. A lesser-known element … and one that harmed far more people was the witch-hunt McCarthy and others conducted against homosexuals.” The West Coast radicals regarded Norman Thomas, then the party’s leader, as too moderate, and themselves as revolutionary democratic socialists. David had sent a letter to Thomas in that spirit, but his move to New York City was itself a new lesson in reality, and was followed a year later by another letter to Thomas apologizing for any dogmatism. Though David did, in fact, become a leading member of the left wing of the Socialist Party.

During a trip to Germany after World War II, McReynolds stood in the ruins of Bremen and had what he described as a “religious experience,” though he would call himself a “Buddhist atheist” and then a “religious atheist” in later years. In an interview later filmed in his New York apartment, he also said we all come into life from “some source” to which we return. From the time of his visit to Bremen until his death, he worked as a peacemaker and opposed all wars. He became a member and spokesman of the War Resisters League and ran as a candidate for the Socialist Party, the Peace and Freedom Party and the Green Party.

McReynolds’ conversion experience in Bremen was of the kind the Apostle Paul had on the road to Damascus, though within a bombed-out city and thus within a starker secular horizon—one within which official Christendom, and not just the fascist cult of blood and soil, had played a decisive part. By choosing the word “religious,” McReynolds meant the kind of insight that has a radical dimension, going to the roots of our being. Indeed, the Latin root of the word “radical” is radix, meaning root. The organic function of roots involves the conserving of soil and the metabolism of elements necessary to the growth and branching of plants above ground. In radical movements, social memory and present circumstances become the ground of being within a given social climate. The growth of these movements is both constrained by necessity and open to possibility.

I am paraphrasing the words of A.J. Muste here, since I can’t find his very words, but he wrote that the problem with war is the winners, since they think the next war will also prove to be a winning proposition. The endless wars waged by the United States, especially since World War II, have delivered no such decisive victories. On the contrary, this country has sown the seeds of bitter suffering and prolonged enmity from Korea to Vietnam, from Afghanistan to Libya, from Iraq to Syria. Entrepreneurs in Vietnam, especially in the tourist economy, present one face to visitors, while other Vietnamese remain grief-stricken and some still bear the physical scars and wounds of that war.

Moreover, the United States often uses its power and influence in class struggles and civil wars around the globe, distinct from full-scale military invasions or flyover bombing campaigns. In these cases, local and regional alliances are made through state diplomacy, CIA campaigns and sometimes through military aid and training of the kind that rarely makes broadcast news unless American soldiers are killed.

McReynolds got his FBI file of nearly 400 pages through the Freedom of Information Act, and he was both dry and wry in describing what they got right and what they got wrong. Mostly right about his homosexuality, and the years when he was a heavy drinker. Wrong when his file stated he was a Trotskyist, which the FBI accepted as fact based on a report of his politics made by the Political Commission of the Communist Party in Los Angeles. He was amused that the FBI took that party as a conveyor of any accurate information in his case, since a general charge of Trotskyism was used in the purges and show trials under Stalin and was a term of polemical abuse in the wider communist movement in the following decades.

McReynolds associated with many communists in various groups and movements, but was never a Leninist of any kind. McReynolds described himself as “a democratic Marxist,” but he had no illusions about what he described as “Lenin’s coup d’état” in Russia. McReynolds was never disillusioned by “the god that failed,” because he was never tempted by any kind of socialism that did not grow from the ground up through free speech and free assembly. In most practical coalitions, he acknowledged that many communists were good organizers unrestricted by the Kremlin. Opposing Red-baiting campaigns during the McCarthy period and the longer Cold War was a civil libertarian duty for McReynolds and many others.

He was a fine point-by-point debater in public, though his writing was uneven because he took on so many practical tasks as an activist and organizer and thus met deadlines in a rush or not at all. In the late 1960s and early 1970s he was also a heavy drinker, until friends and comrades helped him confront a bad habit and break it. Keep in mind that McReynolds remained an active organizer against war and for peace in those years, despite a drinking habit that sometimes interrupted his work.

Before I met him in 1973, I had been reading some of his articles in radical magazines such as WIN and Liberation, now long gone. There are real gems among his writings, reflecting a wide horizon of historical and cultural interests. He chose a bohemian way of life, like many writers and artists of his generation, and this ruled out the careerism that has proven so deeply corrosive to both public life and culture. Though he received some financial support from family, friends and comrades, his income remained marginal.

The Socialist Party never regained the membership and wide influence of the early years when Eugene Debs was still living. McReynolds was always honest about such facts and wrote, “Our high point came before the 1920’s, though we kept thinking that the past was prelude to the future. Debs got 5% of the vote while in Federal prison for opposing the First World War. We were never again to get anywhere close to that.”

The Socialist Party has been honorable in keeping democratic socialism in public conversation, and McReynolds was steady in keeping the Debsian tradition current among its members. In the early 1970s, the majority of members favored “realignment,” and took up the project of reforming the Democratic Party from within. Two main factions in that realignment emerged, one of which founded Social Democrats USA. The other one followed Michael Harrington into the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Some of the Social Democrats leaned so far to the right that they accommodated themselves in both Democratic and Republican administrations, and even became notable figures among the neoconservatives. The neoconservatives ended up supporting neoliberal projects of “welfare reform,” austerity and state corporatism. Indeed, neoconservatism and neoliberalism have now become a distinction without a difference.

The DSA members followed what they regarded as “the left wing of the possible,” in the words of Harrington, but were marginalized by the “centrism” and war policies of the career politicians in the Democratic Party. McReynolds was a crucial figure in the smaller Debs Caucus, which re-founded the Socialist Party as an independent party of democratic socialism. Even if this episode had been the sum of his contribution to socialism in the United States, he would deserve recognition. In fact, he was a steady worker for the causes of peace, civil rights and socialism during his long life.

McReynolds named Muste and Bayard Rustin as the two main mentors and comrades who were formative in his own worldview and analysis of events. All three became members of the War Resisters League. Muste came from a working-class Dutch Calvinist background, had been the founder of a Marxist party, and was a key leader of the bitterly fought and successful Electric Auto-Lite strike in Toledo, Ohio, in 1934. Muste turned toward Christian pacifism and became a member of the religious Fellowship of Reconciliation and of the secular War Resisters League. Muste also became a member and leader of the peace movement during the Vietnam War, which the Vietnamese more justly call the American War.

Rustin was raised by grandparents in a middle-class home in which W.E.B. Du Bois and other black writers and leaders were often guests. His grandmother was a Quaker who attended services at an African-American Methodist Episcopal church with her husband. Muste and Rustin later became Quakers and close associates of Martin Luther King. Rustin became a key strategist in the civil rights movement and in the 1963 civil rights march on Washington, at which King gave the speech known as “I Have a Dream.” In later life, Rustin drifted into neoconservative circles, not easy to square with his earlier Gandhian principles. McReynolds, who had already practiced civil disobedience in the cause of peace, was also arrested and jailed in the cause of civil rights.

When King read Henry David Thoreau’s essay “On Civil Disobedience” as a college student, he later wrote that these ideas illuminated his own path going forward. Thoreau spent a night in jail for his refusal to pay a poll tax and was not grateful when it was paid by others. Thoreau acted in resistance against a republic that still tolerated slavery. Thoreau’s family was active in the underground railroad, helping black Americans escape slaveholders. An anecdote, perhaps apocryphal, relates a visit of Ralph Waldo Emerson to Thoreau in jail. Emerson asked, “David, what are you doing in there?” Thoreau replied, “Ralph, what are you doing out there?” Thoreau was not a pacifist, and it is sometimes forgotten that he supported the white abolitionist John Brown in taking up arms against slavery.

Gandhi had also read Thoreau’s essay, but he took civil disobedience in a pacifist direction during his campaigns against British rule in India. Thus, the Gandhian campaigns became one of the moral and strategic models for many civil rights campaigners in the United States, including Rustin and King. McReynolds’ pacifism was not dogmatic, since state violence might sometimes rouse people to acts of resistance beyond his own Gandhian principles. Gandhi himself had said that peaceful resistance was the better path, but that other forms of resistance were better than no resistance at all. Citizens of imperial powers cannot, in any case, dictate the methods of struggle to people around the world. If we are committed to peace, then we are obliged, first and foremost, to obstruct and finally dismantle the war machine within our borders. On this point, McReynolds refused all moralism without losing his moral bearings. Indeed, he said he was not sure he would be willing to die in a struggle against war but was willing to go to jail when necessary.

Gandhian pacifism was central to the life and work of people such as Barbara Deming, who also worked in the women’s movement as an open lesbian. Her guiding motto was “No one is Other.” Her Gandhian take-home message was “clinging to the truth,” in concord with Gandhi’s faith in satyagraha, a Sanskrit compound word meaning the power of truth. She thought, however, that this truth was not simply given by faith but was found in open dialogue. Her long friendship with McReynolds was tested by their disagreements about feminism and the gay rights movement, as documented in the dual biography by Martin Duberman, “A Saving Remnant: The Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds.”

McReynolds would change his views over time, and was open to feminist writers in his editorial work. He had joined an early public protest of gay people in Philadelphia, under a dress code of dresses for women and suits and ties for men, a public mark of the more conservative “homophile” groups, but he was not among the organizers. He did not come out on the public record until he wrote an article on gay issues in WIN magazine, just after a police raid on the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, when the customers and gay neighbors responded with a street rebellion lasting three nights in June 1969. At least one of the obits published since McReynolds’ death quotes someone claiming he “was in the forefront of gay rights,” which is nonsense. With few exceptions, male leftists went AWOL from the early struggles of women and gay people, excusing their lack of solidarity by claiming devotion to class struggles—as though workers are not also women and gay people.

Like much of the old left (including the New Left of the previous century), McReynolds had a political agenda that placed the women’s and gay movements in a secondary or tertiary rank. To his credit, he did not become one of the professional bores and talking heads who are again opening fire at identity politics in venues across the political spectrum, from left websites to op-ed pages in The New York Times. Identity politics first came to real notice in the Combahee River Collective Statement, written by a group of class-conscious feminists and lesbians of color. That’s a fact today’s critics easily forget or maybe just never knew. They claim to defend “universal” ideas and values, but the universal means nothing without the particular. Indeed, when the particular circumstances of class struggles and social movements are overlooked, then the socialist movement within and across borders is impoverished.

McReynolds’ early home life, his homophobic father, the police raids on the gay community and the official morality of this country all left a deep imprint upon him. Even late in life, as noted in Duberman’s book, McReynolds wrote that he would “probably go to my grave with a sense of guilt about homosexuality.” McReynolds would credit his encounter with Alvin Ailey in a UCLA men’s room as an event that left him “walking on air.” They became good friends, and Ailey later become a dancer and the founder of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. McReynolds claimed that Ailey was the first gay man he’d met who was “not nervous, not guilty” about homosexuality. In personal life, McReynolds offered his support to gay friends and comrades, including Rustin, who had been arrested for “lewd acts” with two young men. In a letter McReynolds wrote to Rustin in 1953, he referred to their common “problem” and to himself as a “fallen brother.”

This was a time when Muste declared to fellow pacifists that Rustin should be unwelcome in the leadership of the peace movement. McReynolds knew of one comrade who had been expelled from the Young People’s Socialist League for being gay, and various Marxist parties even had official policies against gay membership. The Socialist Party branches in Los Angeles and New York were more tolerant, and McReynolds claimed “everyone knew” about his homosexuality in his own bohemian, pacifist and socialist circles. An open secret in such circles was at least better than sectarian discipline elsewhere on the left, and better than the organized campaigns against Reds and queers in government, duly reported during the McCarthy era in The New York Times. McReynolds had been so accustomed to the closet he shared with so many other gay people that he also grew accustomed to the ready-made closet of the left, where gay comrades were still subject to a double standard. The open secret required gay comrades to be vigilant over matters straight comrades simply took for granted. McReynolds, indeed, casually expressed aversion to the “swishy” men he sometimes met in gay bars, and was mostly puzzled by later gender-benders and trans people who dared to go public.

As for the nonviolent protests of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), McReynolds was not on the public record even in a statement of support, so far as I can find. Likewise, most of the official left kept its distance, though ACT UP was a signal social movement in the struggle for health care. Of course, the militant chants and actions that disrupted law offices, political campaigns of career politicians and a Mass at New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral went far beyond the older traditions of civil disobedience. ACT UP dared to take Cardinal John O’Connor at his own word as a moral leader, and to his morals we opposed our own. Since he made the Catholic Church a political ally of government neglect and barbarism, we brought people living with and dying of AIDS into the streets and into the cathedral where Cardinal O’Connor led the Mass. Many radical Catholics joined us. This was one of our most controversial public actions, and a firestorm of condemnation followed. We challenged the church years before the sexual abuse scandals really broke into full public knowledge.

I was a co-founder of an ACT UP chapter in Philadelphia, and we disrupted one of Bill Clinton’s fundraisers by chanting “HIV is not a crime! Why are Haitians doing time?” So long as we went after Republicans, some Democrats were content. When we went after Democrats, they thought we had crossed the line. Indeed, that line even ran through the wider ACT UP network, and of course class divisions run through every social movement.

Class-conscious civil disobedience deserves full discussion among socialists and within radical social movements. Socialists must never forget that any labor strike, and especially any general strike, will always embody an element of class coercion in ongoing class struggles. Moreover, the ruling class always gets a vote in whether outright violence is employed or not. Making the kind of peace we want also means making the kind of justice we want, and the whole tradition of civil disobedience requires a critical review in both theory and practice. Socialists should orient ourselves to the most class-conscious members of social movements, but we can only do so by being honest and organic members of these movements of popular resistance. The “unity of the left” can only emerge from the ground of solidarity, and any party of democratic socialism that is not rooted in this ground may have a fine program and still dwindle into a debating club. A good theory will not be good enough without communal practice beyond any partisan project whatsoever.

Socialism means workers own and run their own workplaces, or else it means some managerial form of social democracy. Of course, social democracies are examples of “mixed economies,” in which councils and cooperatives run by workers and neighbors prefigure a change in production, consumption and distribution. The relation of means and ends remains problematic, however, since a local clinic, food market or housing collective will still be swimming against the current of corporate culture. Anarchist collectives are not necessarily at odds with the libertarian left goal of a freely federated council republic, which is shared by some democratic socialists.

No “inside/outside” strategy proposed by some members of the left has ever altered the theoretical “centrism” of the Democratic Party, nor its practical corporate consensus with the Republican Party. Whether it comes from the Communist Party or the Democratic Socialists of America, such a strategy is at odds with an independent party of democratic socialism working in solidarity with rebel workers and social movements.

The DSA has a new wave of members inspired by the campaign of Bernie Sanders, and by other campaigners, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Naturally, any democratic socialist should welcome a much wider public conversation about workers and electoral politics. Some of the younger DSA members are quite critical of the Democratic Party, so they may finally beat their heads against the bunker of the DNC before moving on to other camps of socialism. To McReynolds, some of the new DSA members sounded like the older sectarians, so he wondered if they had forgotten the better ideas of Harrington. As McReynolds did not spell out his concerns, maybe he thought a new crew of sectarians were just pursuing the old strategy of “entryism,” without much devotion to democracy.

McReynolds himself was once a stern critic of Harrington. In 1969, when McReynolds urged the Socialist Party to pass a resolution calling for the unilateral withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam, it was defeated by a three-to-one margin with the help of Harrington and the followers of Max Shachtman. McReynolds called Harrington “the gutless wonder of the socialist movement … the war is still, in his mind, tragic, but it is still impossible for him to choke out the words ‘get out,’ even in a whisper.” Instead, a pro-war resolution was passed that defined the conflict as “one of democracy versus totalitarian communism.” McReynolds was appalled but remained active in the Debs Caucus. Harrington backtracked from that resolution, but remained aloof from civil disobedience against the war. Shachtman’s followers later became professional anti-communists and neoconservatives.

We need a peace movement now that goes beyond mass protests to sustain ongoing political resistance to war and empire. Such a movement has to be class conscious, or it won’t be grounded and get traction going forward. Socialists should be active in such a movement, but we’d be out of our minds if we demanded that the whole movement should be socialist. A class-conscious peace movement should hammer on the unaccountable war and military budget that actively defunds common goods and services—everything from health care to education to housing to infrastructure. The ecological crises bearing down on all species can only be mentioned here. To the credit of the Socialist Party, it worked with other socialists and Green Party members to organize an Ecosocialist Conference in Los Angeles in 2013, held in a former police station that had become a library and an African-American arts and community center.

In later life, McReynolds grew less active in the Socialist Party, and once described himself as “a peace movement bureaucrat.” He was a great deal more than a bureaucrat as a peacemaker, but he could often be self-deprecatory. He took his organizational duties seriously, but he was also a deeply principled leading member of the peace movement. In my view, his work in the peace movement was of greater lasting significance than his work in the socialist movement. As for his work as a socialist, McReynolds was so determined to avoid the sectarian bad habits of the left that he often fell into other habits of opportunism, hoping the left might gain ground by taking shortcuts through certain Democratic Party campaigns.

In 1973, when Igal Roodenko first introduced me to McReynolds in the broken-down building then known as the Peace Pentagon, which housed the offices of groups including the War Resisters League and the Socialist Party, I was an 18-year-old pacifist and anarchist. I had met Roodenko when he came to speak at Pendle Hill, a Quaker community and study center in Pennsylvania, and a minor scandal ensued when he spent his last night there in my room. The age gap likely concerned a few older Quakers more than the sex, though I assured them I had a mind of my own, or why would I be studying the pacifist dissenters of the 17th century?

Roodenko was an anarchist member of the War Resisters League and also deserves a place in our social memory. He wrote a letter to McReynolds stating that he would break off their friendship if McReynolds did not break off his heavy drinking. McReynolds was moody and busy the day I met him, though we were soon exchanging letters with real metal hitting real paper. (The old typewriters could be a nuisance, but they were artisan tools and I still miss them during computer meltdowns.) We disagreed even then about the possibilities of electoral politics, and not just because I was an anarchist, but our main argument concerned feminism, the gay movement and radical changes in culture. Shortly after I turned 20, I met Larry Gross, and we were among the co-founders of the Lavender Left and among the organizers of the first two national gay marches on Washington. We’ve been together over 40 years, and my work as a writer and activist owes much to his steady support.

Many years passed before McReynolds and I corresponded again by email from coast to coast, and by then our disagreements focused on the practice of democracy, whether outside or within partisan politics. McReynolds and I resigned from the Socialist Party at the same time, shortly after a close vote of the party’s national committee to censure him for comments he had made on a personal Facebook page, and which in no way were presented as party positions. The censure concerned his comments on Islamic extremism, and also on the killing of Michael Brown by the police. He had called Brown “thuggish” in regard to Brown’s physical intimidation of a shopkeeper. So would I.

McReynolds detested all religious extremism, and he certainly condemned the brutality and impunity of so many police. The censure was a sly ambush, since McReynolds was never contacted before it was made, nor was there any open discussion among party members before a vote for or against censure could be taken. I would have voted against. In the event, McReynolds and I both felt there was an element of generational animus in the censure. Our civil-libertarian convictions were on the same page, and we both wondered why democracy within the party was taken so lightly. Yes, and I also wondered, “Who is next?”

The practice of writing personal and political letters is becoming eccentric. Even the messages between McReynolds and me grew more telegraphic, and in this way email often tends to revert to Morse code. McReynolds had a Facebook account, whereas I am mostly allergic to social media, so in that respect he became a modernist and I became an antiquarian. Twitter is now the favored means of communication of the Demagogue-in-Chief, so well suited to his 3 a.m. rages and revenges. Well, if the public only gets to choose between two phony populists, many of them will vote for the Middle Finger. That is in part class fury, though not yet class consciousness.

McReynolds is not above criticism, but few of his critics share equal courage in facing reality, in risking arrest, and in the integrity of his commitment to class-conscious democracy. In his wide range of cultural and historical reference, he does seem almost antique against the background of popular culture. In his enjoyment of popular culture he had his own personal taste, but it was not his home ground, and he did not bother to keep up with the tastes of the young.

McReynolds was generally a good uncle among young radicals, who deserve a period of grace while finding their own goals and voices, and who did not always treat him kindly. He was even snubbed by certain elders of the left, who may be more deeply versed than McReynolds ever was in the scriptural canon of Marxism, but who have never been free spirits and are not good examples of his best human qualities. He was finally stranded on the shore of a receding time and culture, something many of us are likely to experience should we live so many years. His legacy is now a message in a bottle, ready to be found by those living on our endangered shores and rising seas.

McReynolds was critical of state regimes under Red flags, he was skeptical of fashionable currents of post-modernism, and he offered counsel to people inclined to believe that youth alone is a signal qualification for social change. He was a Marxist who was never a close reader of Marx, as he freely confessed, and in his ideals belonged to the libertarian left. In his heart of hearts, the old and ever-new flame of a rebel spirit was never extinguished, and in that sense these words of the militant Spanish anarchist Buenaventura Durruti are McReynolds’ best epitaph:

“The bourgeoisie might blast and ruin its own world before it leaves the stage of history. We carry a new world here, in our hearts. That world is growing in this minute.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.