D.J. Waldie on the Cult of Baseball

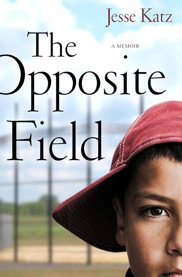

"The Opposite Field," a memoir by Jesse Katz, is a moving meditation about baseball, politics, and the unease of negotiating a new kind of American place.In "The Opposite Field," Jesse Katz delivers a moving meditation on youth baseball, politics and a new kind of American place.

Baseball—that old-time national religion—is a memory cult. Every play, with its long prelude and dénouement, exists for the purpose of recollection. A baseball game is properly its box score, a post-game row of mournful or joyful numbers. More mysteriously, baseball is a cult of young men’s bodies as seen by the older men—fathers, coaches—who watch and handle those bodies; men whose own bodies bear marks of the game, aging bodies that tense in sympathy with the lunge of a catch, the torsion of a windup and the breathlessness of a slide to home.

Jesse Katz, a former street gang reporter for the Los Angeles Times, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, a Portlander transplanted to L.A., and a worshiper of the game, packs memories and bodies into “The Opposite Field,” a sweet baseball memoir with unexpected elements of politics, the ethics of cultural appropriation and the unease of negotiating a new kind of American place.

Katz starts with the old faith’s essentials: a baseball diamond and a boy. The diamond is La Loma field in Monterey Park, just beyond the eastern edge of downtown Los Angeles where barrio becomes suburb. The boy is Max, his son—“maple colored,” a mestizo, the only Jewish Nicaraguan in East L.A. “I have rinsed his wounds at La Loma,” Katz writes of Max, “iced him, kneaded him, bandaged him, scooped him off the ground, his face streaked with sweat and clay and eye-black grease, and held him in my arms.”

Katz extends his embrace beyond the brown body of his son and his own memories of Little League games. He has gotten the dirt of La Loma under his skin and he will not rub the stain of it out. La Loma is his memory palace, his dating service and his fatherhood proving ground. La Loma is his temple on a hill in L.A.

La Loma also is the turf of the Monterey Park Sports Club, a ramshackle organization, a mostly Latino youth baseball league in mostly Asian Monterey Park (once marketed to anxious Hong Kong families as “The Chinese Beverly Hills”). But weird ethnographies are everyday reality in the Los Angeles heteropolis, where taco trucks run by a Filipino-American sell Korean barbecue to Anglo hipsters. Maximum hybridity is an L.A. cliché.

Katz thinks of himself as a border-jumping, Castilian-inflected, Bennington-educated outsider, one who can more easily interview L.A. gangsters because he speaks the stilted Spanish of their grandparents and belongs to no discernable faction. And he isn’t the odd Jew among Latinos that he thinks he is. He’s just another Anglo or just another Angeleño—that amphibious being whose demographic status slips from minority to majority depending on the time of day, the neighborhood and the route of his commute. For Katz, baseball is about lines and rules, some of the rules requiring Talmudic reinterpretation to make them work in the real world. Los Angeles is that world, where most boundaries are poorly defined and where we invent the rules daily.

The Monterey Park Sports Club needed rules when Max signed up for T-ball and Katz became the volunteer coach of his team. Until then, the veteranos of the club had been quietly taking a cut from registration fees, snack bar sales and the purchase of uniforms, equipment and trophies. Worse, Katz discovered, the joy of baseball at La Loma was being spoiled by the old regime through its meanness, its callousness toward talentless players and its faithlessness in the service of the game.

To save the game—to prolong a boyhood of afternoons—Katz reinvented himself as the “commissioner” of La Loma baseball, out-hustled his detractors, swelled participation by hundreds of new players and kept the accounts clean. He is everyone’s rabbi. In season and out, Katz remains a believer in parks-and-rec baseball, the return of spring, and tradition. Father and son bond over baseball, fall out in the usual ways of fathers and sons and ultimately reconnect on the fields of La Loma, where every player, however much a nebbish, gets a trophy, gets the opportunity to remember and be remembered in the game. “Standing in the center of it all,” Katz concludes, “I looked around in amazement at what we had created, how a park that had been given up for dead was now spilling with life. It was wonderful and messy … mixed up with all the complications of race and class and geography and culture, somewhere between Touch of Evil and Desperate Housewives.”

I read “The Opposite Field” when it was still in manuscript in order to write a jacket blurb. I liked the book and said so. I liked the book’s regard for nondescript Monterey Park, for the wonder Katz has in the changing fortunes of his ball-playing son, and even the sentimentality that Katz sometimes fails to hold in check. I liked his tenderness toward the rough congregation of players and parents that gathers at La Loma. I liked his faithfulness most, even if it’s to the lesser religion of baseball.

I still like the book, but what interests me now is this story’s other field. Not the one of dreams, but the field where Katz is the false Chicano fully aware of that pose, where Katz presumes to bring orthodox baseball to wayward La Loma, where Katz answers his longing to be the lover of brown women’s bodies. All of that speaks to Los Angeles as it is—inauthentic, provisional, yearning—a Spanglish ballad of working people making some kind of life, or running from one, in immigrant, aspirant L.A.

“The Opposite Field” is a lot like Los Angeles. It’s about desire and its consequences, some of them awful. Consequences rarely inhibit desire here. Katz longs so much for a ball-playing son that he wills an almost perfect La Loma into existence for himself and his boy, although the costs are high (for Katz, a divorce, affairs, a failed relationship with a stepson, and the burden of a son’s obligations for Max). Willing an almost perfect place into existence is the story of Los Angeles, where the cost has been almost too much.

An empty field, unmet desires and the temptations al otro lado—on the other side—the other side of the continent, of downtown, of the city’s ethnic margins; Los Angeles and La Loma both begin with these possibilities. Having played with the essentials of the place he calls home, Katz hasn’t quite hit a home run in “The Opposite Field.” But he has sailed a fly ball deep into what it means to be an Angeleño. It will be fielded and remembered, I hope, by readers who love the game, love the possibilities of redemptive Los Angeles, as much as Jesse Katz does.

|

D.J. Waldie is a contributing editor for the Los Angeles Times and a contributing writer at Los Angeles magazine. His most recent book is “California Romantica.” He blogs at www.kcet.org/local. |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.