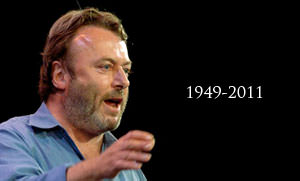

Christopher Hitchens: Reason in Revolt

What zeal this man had to eviscerate the conceits of the powerful, whether their authority derived from wealth, the state or a claim to the ear of the divine .

Hitch is dead. Not, obviously, his brilliant body of work, or the stunning examples of a grand and unfettered intellect that will forever survive him, as will the indelible record of his immense wit and passion. But, sadly, a life force that I had assumed as an indissoluble part of our political and literary landscape, as well as my own close circle of friends, has ended, and with it an indispensable element of our collective moral code.

Christopher Hitchens could be wrong; we had harsh public debates about the Iraq War, but I never doubted that, even then, he was coming from a good place of humane concern. In that instance, he allowed his great compassion for the Kurds and his justifiable loathing of Saddam Hussein to overwhelm a lifetime of opposition to the arrogant assumptions of America’s neocolonialism. Despite the vehemence of our debates, both public and personal, he and his saving grace and wife, Carol Blue, held a gathering at their home to discuss a book I wrote on the subject. This was a man unafraid of intellectual challenge and committed to pursuing the heart of the matter.

That was his driving force, a seeker of truth to the end, and a deservedly legendary witness against the hypocrisy of the ever-sanctimonious establishment. What zeal this man had to eviscerate the conceits of the powerful, whether their authority derived from wealth, the state or a claim to the ear of the divine.

Hitch was the opposite of the opportunistic pundits who competed with him for public space. He took immense risks, not the least in offering himself for waterboarding before concluding it was unmistakably torture, or challenging the greatness of God, knowing full well that he was exposing himself as an object of wildly irrational hate.

So it ever was with the Hitch I knew for decades, going back to the young ex-Trotskyite challenging ex-Communist and fellow Brit writer Jessica (Decca) Mitford through nights of lively debate about everything, and then joining that equally grand and kindred spirit in several drunken and rousingly heartfelt renditions of “The Internationale.” Much like Mitford, Hitchens became world famous and well rewarded and, like her, Hitch was to the end singing that worker’s anthem on behalf of the deluded and abused masses with whom, for all of his personal success, he most profoundly identified.

He was a great man, perfect in his intellectual courage, but I am reminded more of the writer, profoundly dedicated to his craft and committed, for all of his sparkle and bouts of excess, to a prodigious workaday effort at making this a better world. In his memory I offer these lyrics from “The Internationale,” as I recall his somewhat inebriated and ever bemused, but no less heartfelt, rendering of these verses:

Arise ye workers from your slumbers

Arise ye prisoners of want

For reason in revolt now thunders

And at last ends the age of cant

Away with all your superstitions

Servile masses arise, arise

We’ll change henceforth the old tradition

And spurn the dust to win the prize.

That was him. A slayer of superstitions, thundering reason in revolt.

Lift a glass to comrade Hitch.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.