Border Wars in the Homeland

Shena Gutierrez was already cuffed and in an inspection room in Nogales, Ariz., when the Customs and Border Protection agent grabbed her purse, opened it, dumped its contents onto the floor, and began to trample on her life, quite literally, with his black boots. 1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

“Stop stepping on my pictures!” Gutierrez insisted again. But much like the CBP’s official complaint process, the words were ignored. The only thing Gomez eventually spat out was, “Are you going to get difficult?”

When Shena Gutierrez offered me a play-by-play account of her long day, including her five-hour detainment at the border, her voice ran a gamut of emotions from desperation to defiance. Perhaps these are the signature emotions of what State Department whistleblower Peter Van Buren has dubbed the “Post-Constitutional Era.” We now live in a time when, as he writes, “the government might as well have taken scissors to the original copy of the Constitution stored in the National Archives, then crumpled up the Fourth Amendment and tossed it in the garbage can.” The prototype for this new era, with all the potential for abuse it gives the authorities, can be found in that 100-mile zone.

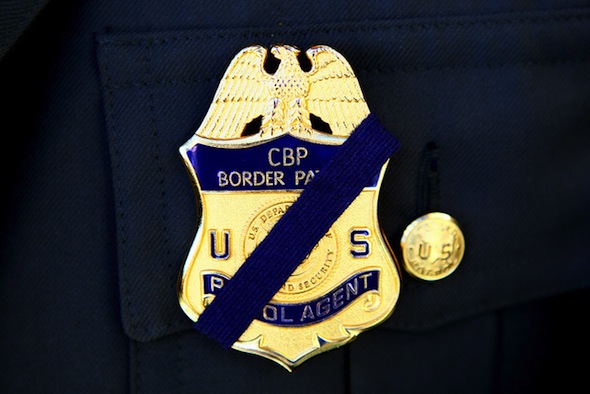

A Standing Army

The zone first came into existence thanks to a series of laws passed by Congress in the 1940s and 1950s at a time when the Border Patrol was just an afterthought with a miniscule budget and only 1,100 agents. Today, Customs and Border Protection has more than 60,000 employees and is by far the largest federal law enforcement agency in the country. According to author and constitutional attorney John Whitehead, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), created in 2002, is efficiently and ruthlessly building “a standing army on American soil.”

Long ago, President James Madison warned that “a standing military force, with an overgrown Executive, will not long be safe companions to liberty.” With its 240,000 employees and $61 billion budget, the DHS, Whitehead points out, is militarizing police units, stockpiling ammunition, spying on activists, and building detention centers, among many other things. CBP is the uniformed and most visible component of this “standing army.” It practically has its own air force and navy, an Office of Air and Marine equipped with 280 sea vessels, 250 aircraft, and 1,200 agents.

On the border, never before have there been so many miles of walls and barriers, or such an array of sophisticated cameras capable of operating at night as well as in the daylight. Motion sensors, radar systems, and cameras mounted on towers, as well as those drones, all feed their information into operational control rooms throughout the borderlands. There, agents can surveil activity over large stretches of territory on sophisticated (and expensive) video walls. This expanding border enforcement regime is now moving into the 100-mile zone.

Such technological capability also involves the warehousing of staggering amounts of personal information in the digital databases that have ushered in the Post-Constitutional Era. “What does all this mean in terms of the Fourth Amendment?” Van Buren asks. “It’s simple: the technological and human factors that constrained the gathering and processing of data in the past are fast disappearing.”

The border, in the post 9/11 years, has also become a place where military manufacturers, eyeing a market in an “unprecedented boom period,” are repurposing their wartime technologies for the Homeland Security mission. This “bring the battlefield to the border” posture has created an unprecedented enforcement, incarceration, and expulsion machine aimed at the foreign-born (or often simply foreign-looking). The sweep is reminiscent of the operation that forced Japanese (a majority of them citizens) into internment camps during World War II, but on a scale never before seen in this country. With it, unsurprisingly, has come a wave of complaints about physical and verbal abuse by Homeland Security agents, as well as tales of inadequate food and medical attention to undocumented immigrants in short-term detention.

The result is a permanent, low-intensity state of exception that makes the expanding borderlands a ripe place to experiment with tearing apart the Constitution, a place where not just undocumented border-crossers, but millions of borderland residents have become the targets of continual surveillance. If you don’t see the Border Patrol’s ever-expanding forces in places like New York City (although CBP agents are certainly present at its airports and seaports), you can see them pulling people over these days in plenty of other spots in that Constitution-free zone where they hadn’t previously had a presence.

They are, for instance, in cities like Rochester, New York, and Erie, Pennsylvania, as well as in Washington State, Vermont, Florida, and at all international airports. Homeland Security officials are scrutinizing people’s belongings, including their electronic devices, from sea to shining sea. Just ask Pascal Abidor, an Islamic studies doctoral student whose computer was turned on by CBP agents in Champlain, New York.

When an agent saw that he had a picture of a Hezbollah rally, she asked Abidor, a U.S. citizen, “What is this stuff?” His answer — that he was studying the modern history of the Shiites — meant nothing to her and his computer was seized for 10 days. Between 2008 and 2010, the CBP searched the electronic devices of more than 6,500 people. Like many of us, Abidor keeps everything, even his most private and intimate conversations with his girlfriend, on his computer. Now, it’s private no longer.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.