Tom Hayden’s New Port Huron Statement

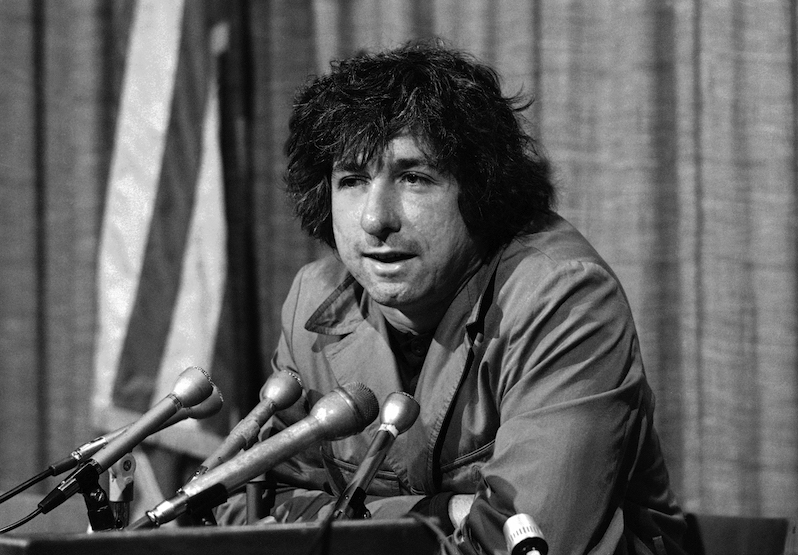

From the archives: The veteran social activist wrote a new preface to the manifesto that helped shape a generation's views on racial equality, participatory democracy and the military-industrial complex. Political activist Tom Hayden in 1973. (George Brich / AP)

Political activist Tom Hayden in 1973. (George Brich / AP)

Editor’s note: Tom Hayden, an activist, author and longtime Truthdig contributor, died Sunday at age 76. In his memory, Truthdig will share one of Hayden’s pieces each day this week. This story was originally posted on April 10, 2006. *** Editor’s note from 2006: In May of 1962, 21-year-old Tom Hayden, a founding member of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), took the lead in drafting “The Port Huron Statement,” the manifesto of the SDS and a handbook for a generation of student activists.

As a student at the University of Michigan, Hayden believed that apathy bred by middle-class comfort was a major obstacle to social justice for the oppressed. The Port Huron Statement called on students to leave the ivory tower and seek that justice through direct participatory democracy. The document also railed against the military industrial complex, racial bigotry, and the spread of nuclear weapons.

Hayden went on to travel the world as an activist, journalist and defender of human rights, in addition to serving in the California legislature for 18 years. In September 2005, he re-issued The Port Huron Statement with a new introduction. … As a new preface to that introduction, Hayden has written a short essay for Truthdig about how the legacy of that document continues to find expression in the current generation of young activists.

Specifically, Hayden writes about Rachel Corrie, a 23-year-old American college student who was killed by an Israeli bulldozer in 2003 while protesting the Israeli destruction Palestinian houses in Gaza. Hayden finds in Rachel Corrie a powerful moral example of commitment to social justice.

In the preface and introduction that follows, Hayden offers a personal story of political awakening and commitment as an inspiration and wake-up call to those willing to shake the apathy of comfort for a life of activism and ethical commitment.

Rachel Corrie, I believe, would have been a Students for a Democratic Society activist 50 years ago. The spirit of my Port Huron generation certainly lived in her as she was crushed by an American-made Israeli bulldozer while bearing witness to injustice against Palestinians in 2003. I say this because I believe it to be true, but also to call up the real meaning of the Port Huron statement from the cobwebs of time. I do so with urgency because there are forces today that want to blur Rachel Corrie’s moral example by shutting down a play based on her diaries in New York City at this moment. I protest before their cultural bulldozer.

I never knew Rachel Corrie, but her parents spoke in our Los Angeles home not long after her death, and I have met some of her friends. Her diaries, together with her parents’ account, remind me poignantly of the days long ago when those of my generation bore witness in places like McComb, Miss., Albany, Ga., and Selma, Ala. We took seriously what we had learned in school or from our families, and wanted to put the lessons on the line, close the gap between rhetoric and reality. In these times, young people like Rachel Corrie have left their safe, white Portlands behind to explore what solidarity means in places like Palestine, Chiapas, Central America, Bolivia and Venezuela. They seek justice, and they seek it now. They commit their middle-class skills and, if necessary, their lives to working with those who have no prospects amidst plenty, in hopes of awakening America’s conscience.

Those who want to censor Rachel Corrie’s voice today remind me of those who tried to censor the voices of my generation long ago. Then, as now, they said morality was complex, not simple, that context was overriding, that if we stood against racial injustice in Mississippi it would be exploited by Communists in other lands. That racism and brutality in America, however regrettable, could never be considered equivalent to racism and brutality in other, more sinister, places. That there was no moral equivalence between American killing and Communist killing. And so we had to bury our own dead who were dredged out of a Mississippi swamp while their families wept angry tears.

As you can imagine, we found this complexity too complex to accept morally. After all, it was not the Soviets who killed, beat or jailed the civil rights workers, but Americans with the protection of American officials, from the Neshoba County sheriff to the director of the FBI. It has taken over four decades for the families to see the beginnings of legal justice and accountability. Similarly, it was not Palestinians but Israelis who killed Rachel Corrie with American equipment funded with American tax dollars, and who continue to question her story with American collaboration.

The pattern only became more grotesque during Vietnam, when you became pro-Communist if you questioned the killing of innocent people by American soldiers with American napalm paid for with American dollars. You know how that went, and how it turned out.

My question is this: Has Israel now become the moral equivalent of Mississippi then? When will Rachel Corrie’s words and spirit exist free, on their own, the way she died? If my question is disturbing, outrageous and provocative, you will understand the role that idealists must play across the generations, and why the Port Huron Statement is relevant today. I hope my reflections on “the way we were” are helpful in the present.

THE WAY WE WERE: And the Future of the Port Huron Statement

Originally published by Avalon Publishing Group as the introduction to “The Port Huron Statement:The Visionary Call of the 1960s Revolution” Fall 2005.

Outside Port Huron, Mich., where a dense thicket meets the lapping shores of Lake Huron, the careful explorer will come across rusty and timeworn pipes, and a few collapsed foundations, the last traces of the labor camp where 60 young people finalized the Port Huron Statement, the seminal “agenda for a generation,” in 1962. Like the faded camp, the once-young authors, I among them, are now reaching the last phase of life. Memory is all important now, for memory shapes the hopes and possibilities of future generations. It is for these future generations that the Port Huron Statement of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) is being republished in its entirety.

Some wish that our legacy be washed out with the refuse in those pipes. Out of sight, out of mind. For the conservative icon Robert Bork, the Port Huron Statement (PHS) was “a document of ominous mood and aspiration,” because of his fixed certainty that utopian movements, by misreading human nature, turn out badly. David Horowitz, a former ’60s radical who turned to the hard-core right, dismisses the PHS as a “self-conscious effort to rescue the communist project from its Soviet fate.” Another ex-leftist, Christopher Hitchens, sees in its pages a conservative reaction to “bigness and anonymity and urbanization,” even linking its vision to the Unabomber![1] More progressive writers, such as Garry Wills, E.J. Dionne and Paul Berman, see the PHS as a bright moment of reformist vision that withered due to the impatience and extremism of the young. Excerpts of the PHS have been published in numerous textbooks, and an Internet search returns huge numbers of references to “participatory democracy,” its central philosophic theme. Grass-roots movements in today’s Argentina and Venezuela use “participatory democracy” to describe their popular assemblies and factory takeovers. The historian Thomas Cahill writes that the Greek ekklesia was “the world’s first participatory democracy” and the model for the early Catholic Church, which “permitted no restrictions on participation: no citizens and non-citizens, no greeks and nongreeks, no patriarchs and submissive females.”[2] In modern popular culture, authorship of the PHS has been claimed by the stoned hippie played by Jeff Bridges in “The Big Lebowski.”

The story of the 1962 Port Huron convention has been told many times by participants and later researchers, [3] and I will describe it here only briefly so as to focus more on the meaning of the statement itself. The 60 or so young people who met in Port Huron were typically active in the fledgling civil rights, campus reform and peace movements of the era. Some, like myself, were campus journalists, while others were active in student governments. Some walked picket lines in solidarity with the Southern student sit-in movement. More than a few were moved by their religious traditions. My adolescent ambition was to become a foreign correspondent, which was a metaphor for breaking out of the suffocating apathy of the times. Instead, I found myself interviewing and reflecting on Southern black dispossessed sharecroppers; students who were willing to go to jail, even die, for their cause; the civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., as he marched outside my first Democratic convention; and candidate John Kennedy, giving his speech proposing the Peace Corps on a rainy night in Ann Arbor. I was thrilled by the times in which I lived, and I chose to help build a new student organization, the Students for a Democratic Society, rather than pursue journalism. My parents were stunned.

SDS was the fragile brainchild of Alan Haber, an Ann Arbor graduate student whose father was a labor official during the last progressive American administration, that of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Al was a living link with the fading legacy of the radical left movements that had built the labor movement and the New Deal. Al sensed a new spirit among students in 1960, and recruited me to become a “field secretary,” which meant moving to Atlanta with my wife, Casey, who had been a leader of the campus sit-ins in Austin, Texas. While participating in the direct action movement, and mobilizing national support by writing and speaking on campuses, I learned that passionate advocacy, arising from personal experience, could be a powerful weapon.

Haber and other student leaders across the nation became increasingly aware of a need to connect all the issues that weighed on our generation — apathy, in loco parentis, civil rights, the Cold War, the Bomb. And so, in December 1961, at 22 years of age and fresh from jail as a Freedom Rider in Albany, Ga.,, I was asked to begin drafting a document that would express the vision underlying our action. It was to be a short manifesto, a recruiting tool, perhaps five or 10 single-spaced pages. Instead it mushroomed into a 50-page single-spaced draft prepared for the Port Huron convention in May 1962. That version was debated and rewritten, section by section, by those who attended the five-day Port Huron meeting and returned to me for final polishing. Twenty thousand copies were mimeographed and sold for 35 cents each.

The vision grew from a concrete generational experience. Rarely if ever had students thought of themselves as a force in history or, as we phrased it, an “agency of social change.” We were rebelling against the experience of apathy, not against a single specific oppression. We were moved by the heroic example of black youth in the South, whose rebellion taught us the fundamental importance of race. We could not vote ourselves, and were treated legally as wards under our universities’ paternal care, but as young men we could be conscripted to fight in places we dimly understood, like Vietnam and Laos. The nation’s priorities were frozen by the Cold War: a permanent nuclear arms race benefiting what President Eisenhower had called “the military-industrial complex,” whose appetite absorbed the resources that we believed were necessary to address the crises of civil rights and poverty, or what John Kenneth Galbraith termed “squalor in the midst of affluence.”

Apathy, we came to suspect, was what the administrators and power technicians actually desired. Apathy was not our fault, not an accident, but the result of social engineering by those who ran the institutions that taught us, employed us, entertained us, drafted us, bored us, controlled us, wanted us to accept the absolute impossibility of another way of being. It was for this reason that our rhetoric emphasized “ordinary people” developing “out of apathy” (the term was C. Wright Mills’) in order to “make history.” [4] Since many of us had emerged from apathetic lives (neither of my parents were political in any sense, and I had attended conservative Catholic schools), we began with the realization that we had to relate to, not denounce, the everyday lives of students and communities around us in order to replicate the journey out of apathy on a massive scale.

We chose to put “values” forward as the first priority in challenging the conditions of apathy and forging a new politics. Embracing values meant making choices as morally autonomous human beings against a world that advertised in every possible way that there were no choices, that the present was just a warm-up for the future.

Next Page: The Legacy of Participatory Democracy

Footnotes: [1] New York Times Book Review, Dec. 19, 2004 [2]New York Times, April 5, 2005 [3]See Hayden and Flacks, “The Port Huron Statement at 40,” The Nation, Aug. 5/12, 2002; Hayden, “Rebel, A Personal History of the Sixties,” Red Hen, 2003; Todd Gitlin, “The Sixties, Years of Hope, Days of Rage,” Bantam 1987; Richard Flacks, “Making History, The American Left and the American Mind,” Columbia, 1988; James Miller, “Democracy Is In the Streets, From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago,” Simon and Schuster, 1987, 1994; and Kirkpatrick Sale, “SDS,” Random House, 1973. [4]These distinctions are discussed elegantly in Flacks, “Making History.” The Lasting Legacy of Participatory Democracy

The idea of participatory democracy, therefore, should be understood in its psychic, liberatory dimension, not simply as an alternative concept of government organization. Cynics like Paul Berman acknowledge that the concept of participatory democracy “survived” the demise of the New Left because it “articulated the existential drama of moral activism.” [5] The notion (and phrase) was transmitted by a philosophy professor in Ann Arbor, Arnold Kaufman, who attended the Port Huron convention. Its roots were as deep and distant as the Native American tribal traditions of consensus. [6] It arose among the tumultuous rebels of western Massachusetts who drove out the British and established self-governing committees in the prelude to the American Revolution. It was common practice among the Society of Friends and in New England’s town meetings. It appeared in Thomas Paine’s “Rights of Man” in passages exalting “the mass of sense lying in a dormant state” in oppressed humanity, which could be awakened and “excited to action” through revolution. [7] It was extolled (if not always implemented) by Jefferson, who wrote that every person should feel himself or herself to be “a participator in the government of affairs, not merely at an election one day in the year, but every day.” [8] Perhaps the most compelling advocate of participatory democracy, however, was Henry David Thoreau, the 19th-century author of “Civil Disobedience,” who opposed taxation for either slavery or war, and who called on Americans to vote “not with a mere strip of paper but with your whole life.” Thoreau’s words were often repeated in the early days of the ’60s civil rights and antiwar movements.

This heritage of participatory democracy also was transmitted to SDS through the works of the revered philosopher John Dewey, who was a leader of the League for Industrial Democracy (LID), the parent organization of SDS, from 1939 to the early ’50s. Dewey believed that “democracy is more than a form of government; it is primarily a mode of associated living, of conjoint community experience.” It meant participation in all social institutions, not simply going through the motions of elections, and, notably, “the participation of every mature human being in the formation of the values that regulate the living of men together.”[9]

Then came the rebel sociologist C. Wright Mills, a descendant of Dewey and prophet of the New Left, who died of a heart attack shortly before the Port Huron Statement was produced. Mills had a profound effect in describing a new strata of radical democratic intellectuals around the world, weary of the stultifying effects of bureaucracy in both the United States and the Soviet Union. His descriptions of the power elite, the mass society, the “democracy without publics,” the apathy that turned so many into “cheerful robots,” seemed to explain perfectly the need for democracy from the bottom up. The representative democratic system seemed of limited value as long as so many Americans were disenfranchised structurally and alienated culturally. We in the SDS believed, based on our own experience, that participation in direct action was a method of psychic empowerment, a fulfillment of human potential, a means of curing alienation, as well as an effective means of mass protest. We believed that “ordinary people should have a voice in the decisions that affect their lives” because it was necessary for their dignity, not simply a blueprint for greater accountability.

Some of the Port Huron language appears to be plagiarized from the Vatican’s “Pacem in Terris.” [10] That would be not entirely accidental, because a spirit of peace and justice was flowing through the most traditional of institutions, including Southern black Protestant churches, and soon would flourish as Catholic “liberation theology,” a direct form of participatory democracy in Third World peasant communities. This “movement spirit” was everywhere present, not only in religion but in music and the arts. We studied the lyrics of Bob Dylan more than the texts of Marx and Lenin. Dylan even attended an SDS meeting or two. He had hitchhiked east in search of Woody Guthrie, after all. Though never an activist, he expressed our sensibility exactly when he described “mainstream culture as lame as hell and a big trick” in which “there was nobody to check with,” and folk music as a “guide into some altered consciousness of reality, some different republic, some liberated republic.” [11]

The experience of middle-class alienation drew us to Mills’ “White Collar,” Albert Camus’ “The Stranger,” or Paul Goodman’s “Growing Up Absurd.” Our heady sense of the student movement was validated in Mills’ “Letter to the New Left” or “Listen, Yankee!” The experience of confronting structural unemployment in the “other America” was illuminated by Michael Harrington and the tradition of Marxism. Liberation theology reinforced the concept of living among the poor. The reawakening of women’s consciousness was hinted at in Doris Lessing’s “The Golden Notebook” (which some of us read back to back with Clancy Sigal’s “Going Away”), or Simone de Beauvoir’s “The Second Sex.” The participatory ethic of direct action, of ending segregation, for example, by actually integrating lunch counters, drew from traditions of anarchism as well. (At a small SDS planning meeting in 1960, Dwight Macdonald gave a keynote speech on “The Relevance of Anarchism.” [12]) The ethos of direct action leaped from romantic revolutionary novels like Ignacio Silone’s “Bread and Wine,” whose hero, a revolutionary masked as a priest, said that it “would be a waste of time to show a people of intimidated slaves a different manner of speaking … but perhaps it would be worthwhile to show them a different way of living.”[13]

The idea was to challenge elite authority by direct example and to draw “ordinary people,” whether apathetic students, sharecroppers or office workers, into a dawning belief in their own right to participate in decisions. This was the method — call it consciousness-raising — of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a method that influenced SDS, the early women’s liberation groups, farmworkers’ house meetings and Catholic base communities before eventually spreading to Vietnam veterans’ rap groups and so on. Participatory democracy was a tactic of movement-building as well as an end itself. And by an insistence on listening to “the people” as a basic ethic of participatory democracy, the early movement was able to guarantee its roots in American culture and traditions while avoiding the imported ideologies that infected many elements of the earlier left.

Through participatory democracy we could theorize a concrete, egalitarian transformation of the workplaces of great corporations, urban neighborhoods, the classrooms of college campuses, religious congregations, and the structures of political democracy itself. We believed that representative democracy, while an advance over the divine right of kings or bureaucratic dictatorships, should be replaced or reformed by a greater emphasis on decentralized decision-making, remaking our world from the bottom up.

Some of our pronouncements were absurd or embarrassing, like the notion of “cheap” nuclear power becoming a decentralized source of community-based energy, the declaration that “the International Geophysical Year is a model for continuous further cooperation” and the unquestioned utilization of grating sexist terminology (“men” instead of “human beings”) in sweeping affirmations about dignity and equality. We could not completely transcend the times, or even predict the near future: the rise of the women’s and environmental movements, the war in Vietnam, the political assassinations. The gay community was closeted invisibly among us.[14] The beat poets like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg had stirred us, but the full-blown counterculture, psychedelic drugs and the Beatles were two years away.

Yet through many ups and downs, participatory democracy has spread as an ethic throughout everyday life, and become a persistent challenge to top-down institutions, all over the world. It has surfaced in campaigns of the global justice movement, in struggles for workplace and neighborhood empowerment, resistance to the Vietnam War draft, in Paulo Freire’s “pedagogy of the oppressed,” in political platforms from Green parties to the Zapatistas, in the independent media, and in grass-roots Internet campaigns including that of Howard Dean in 2004. Belief in the new participatory norm has resulted in major, if incomplete, policy triumphs mandating everything from Freedom of Information disclosures to citizen participation requirements in multiple realms of official decision-making. It remains a powerful threat to those in established bureaucracies who fear and suppress what they call “an excess of democracy.”[15]

Next Page: The Port Huron Strategy of Radical Reform

Footnotes: [5]Paul Berman, “A Tale of Two Utopias, The Political Journey of the Generation of 1968,” Norton, 1996, p. 54. [6]At various times, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine and Thomas Jefferson wrote approvingly of Indian political customs. As one historian described Iroquois culture, there were “no laws or ordinances, sheriffs and constables, judges and juries, or courts or jails.” These idyllic themes evolved into the 1960s communes, organic gardening and medicine, environmentalist lifestyles, and other practices. See Howard Zinn, “A People’s History of the United States,” Harper Collins, 2003, pp. 1-23. John Adams wrote in 1787 that “to collect together the legislation of the Indians would take up much room but would be well worth pains,” as cited in an excellent collection by Oren Lyons, John Mohawk, Vine Deloria, Laurence Hauptman, Howard Berman, Donald Grinde, Curtis Berkey and Robert Venables, “Exiled in the Land of the Free,” Clear Light, 1992, p. 109. The 1778 Articles of Confederation Congress actually proposed an Indian state headed by the Delaware nation, p. 113. [7]Thomas Paine, “Rights of Man,” Penguin, 1984, p. 70, 176. [8]In a Jefferson letter dated Feb. 2, 1816, cited by Berman, p. 51. [9]Berman, op. cited, p. 53 [10]Retreating both from Enlightenment beliefs in “infinite perfectibility” and negative beliefs in “original sin,” the Port Huron Statement asserted that human beings are “infinitely precious” and possessed of “unfulfilled capacities for reason, freedom and love.” The wording was provided by a Mexican-American Catholic activist, Maria Varela, who quoted from the copy of a Church encyclical she happened to carry. Casey Hayden spoke of those years as a “holy time.” [11] Bob Dylan, “Chronicles, Volume One,” Simon and Schuster, 2004, pp. 34-35. [12]Sale, p. 27 [13]Ignazio Silone, “Bread and Wine,” 1936, Signet 1986; see also Miller, p. 53. [14]For example, the late Carl Wittman, who joined SDS shortly after Port Huron and worked with me as a community organizer in the Newark project, eventually came out of the closet to write “A Gay Manifesto,” a defining document of the gay liberation movement, six years after Port Huron. See David Carter, “Stonewall, The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution,” St. Martins, 2004. Pp. 118-119. [15]The phrase is that of Harvard professor Samuel Huntington, in a speech to the elite Trilateral Commission in 1976, during the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence. Huntington noted that “The 1960s witnessed a dramatic upsurge of democratic fervor in America,” a trend that he diagnosed as a “distemper” that threatened both governability and national security. Huntington proposed there be “limits to the extension of political democracy.” See account in Zinn, op. cited, pp. 558-560. The Port Huron Strategy of Radical Reform

If the vision of participatory democracy has continuing relevance, so too does the strategic analysis of radical reform at the heart of the PHS. Our critique of the Cold War, and liberals who became anti-communist Cold Warriors, bears close resemblance to the contemporary war on terror and its liberal Democratic defenders. The Cold War, like today’s war on terror, was the organized framework of dominance over our lives. This world was bipolar, divided into good and evil, allies and enemies. The U.S.-led Cold War alliance included any dictators, mafias or thieving politicians in the world who declared themselves anti-communist. The Cold War alliance scorned the 70-plus nonaligned nations as soft-on-communism. The U.S. and its allies engaged in violence or subversion against any governments that included communist or “pro-communist” participation, even if they were democratically elected, like Guatemala (1954) and Chile (1970). Domestically, the American communists who had helped build the industrial unions, the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the defense of the Scottsboro Boys and the racial integration of major league baseball, who had joined the war against Hitler, suddenly found themselves purged or blacklisted as “un-American” for the very pro-Soviet sympathies that had been popular during World War II. [16]

The parallels between Washington’s Cold War alliances and today’s war-on-terror coalition (including unstable dictatorships like Pakistan) and between the McCarthy-era witch hunts and today’s Patriot Act roundups of suspicious Muslims are eerie. Then, it was a ubiquitous “atomic spy ring”; today, the ubiquitous Al Qaeda. The externalizing of the feared, ubiquitous, secretive, religiously alien and foreign “communist” or “terrorist” enemy, the drumbeat of fear issuing from “terror alerts” and mass media sensationalism, the dominance of military spending over any other priority, and the ever-increasing growth of a National Security State, all these themes of the Cold War have been revived in our country’s newest crusade.

Of course the “threat” of violence is not imaginary. Raging militants have attacked innocent Americans and are likely to do so again. Our government’s $30-billion intelligence budget failed to stop them. But those who question the current military priorities or dare to speak of root causes — addressing the abject misery and poverty of billions of people that contributed to the growth of communism in the past or Islamic militancy today — are dismissed too often as enemy sympathizers or softheaded pacifists who cannot be trusted with questions of national security (“sentimentalists, the utopians, the wailers,” historian Arthur Schlesinger called them during the Cold War. [17] Today they are accused of “blaming America first” by critics ranging from neoconservative Jeane Kirkpatrick to onetime SDS leader Todd Gitlin. [18] ) During the Cold War the CIA routinely funded a covert class of liberal anti-communists everywhere, from the American Committee for Cultural Freedom to the AFL-CIO to the U.S. National Student Association. [19] There is a direct line, even a genealogical one, from the leaders of those groupings, such as Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz, to their neoconservative descendants like William Kristol, editor of the Weekly Standard, and John Podhoretz, from the 1940s celebration of “the American Century” to today’s neoconservative project the Committee on the New American Century. As for the definition of “the enemy,” during the Cold War it was a conspiracy centralized in Moscow and operated through a myriad of puppet regimes and parties; today it is Al Qaeda, an invisible network consolidated and controlled by Osama bin Laden and a handful of conspirators.

The Port Huron Statement properly dissociated itself from the Soviet Union and communist ideology, just as antiwar critics today are critical of Al Qaeda’s religious fundamentalism and terror against civilians. But the PHS broke all taboos by identifying the Cold War itself as the framework that blocked our aspirations. As a result, SDS was accused of being insufficiently “anti-communist” by some of its patrons in the older liberal-left who had been deeply devoted to the liberal anti-communist crusade. [20]

The truth lay in contrasting generational experiences: We were inspired by the civil rights movement, by the hope of ending poverty, with the gap between democratic promise and inequality as reality. The Cold War focused our nation’s attention and its budget priorities outward on enemies abroad rather than the enemies in our face at home. The nuclear arms race and permanent war economy drained any resources that could be devoted to ending poverty or hunger, either at home or among the wretched of the Earth. Most, not all, of the liberal establishment, the people we had looked up to, left behind their idealistic roots and became allied with the military-industrial complex. Today a similar transition has occurred within the Democratic Party’s establishment. Despite their roots in civil rights and anti-poverty programs, members of that establishment have become devotees of a corporate agenda, promoting the privatization of public assets from Latin America to the Middle East, creating the undemocratic World Trade Organization, whose rules taken literally would define the New Deal as a “restraint on trade.”[21] With the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, many of the same liberals have abandoned their pasts in the anti-Vietnam movement or the Eugene McCarthy, Kennedy and McGovern campaigns, to help pass the Patriot Act, invade Afghanistan and Iraq, justify the use of torture and detention without trial and expand the Big Brother national security apparatus, while leaving the U.S. at the bottom among industrialized countries in its contributions to United Nations programs to combat hunger, illiteracy and drinking water pollution.[22] Consistent with the Cold War era, any politician who questions these priorities, even a decorated war veteran, will be castigated as soft on terrorism and effectively threatened with political defeat. [23]

The Port Huron Statement called for a coalescing of social movements: civil rights, peace, labor, liberals and students. It was an original formulation at the time, departing from the centrality of organized labor, or the working class, that had governed the left for decades, and again causing some of our elders to grind their teeth. The statement reaffirmed that labor was crucial to any movement for social change, while chastising the labor “movement” for having become “stale.” The Port Huron vision was far more populist, more middle class, more quality-of-life in orientation than the customary platforms of the left. The election of an Irish Catholic president in 1960 symbolized the assumed assimilation of the white ethnics into the middle class, and offered hope that people of color would follow in turn. The goal of racial integration was little questioned. Women had not begun to challenge patriarchy. Environmentalism had yet to assault the metaphysic of “growth.” And so we could envision unifying nearly everyone around fulfillment of the New Deal dream. The Port Huron Statement connected issues not like a menu, not as gestures to diverse identity movements, but more seamlessly, by declaring that the civil rights, anti-poverty and peace movements could realize their dreams by refocusing America’s attention on an unfulfilled domestic agenda instead of the Cold War.

The document contained an explicit electoral strategy as well, envisioning the “realignment” of the Democratic Party into a progressive instrument. The strategy was to undermine the racist “Dixiecrat” element of the party through the Southern civil rights movement and its national support network. The Dixiecrats dominated not only the segregationist political economy of the South but the crucial committees on military spending in Congress. The racists also were the hawks. By undermining the Southern segregationists, we could weaken the institutional supports for greater military spending and violent anti-communism. The party thus would “realign” as white Southerners defected to the Republicans, black Southerners registered as Democrats and the national party retained its New Deal liberal leanings. Through realignment, some of us dreamed, a radical-liberal governing coalition could achieve political power in America — in our lifetime, through our work.

This is the challenge which SDS took on: to argue against “unreasoning anti-Communism,” to demand steps toward arms reductions and disarmament, to channel the trillions spent on weapons toward ending poverty in the world and at home. It was the kind of inspired thinking of which the young are most often capable, but it also was relevant to the times. After Port Huron, Haber and I traveled to the White House to brief Arthur Schlesinger on our work, hoping to spark a dialogue about the new movements. There was a handful of liberal White House staffers like Harris Wofford and Richard Goodwin who seemed to take an interest. Also, we had funds from and the goodwill of Walter Reuther, president of the United Auto Workers (whose top assistant, Mildred Jeffrey, happened to be the mother of Sharon Jeffrey, an Ann Arbor SDS activist).

History has completely ignored, or forgotten, how close we came to implementing this main vision of the Port Huron Statement. President John Kennedy and his counterparts in Moscow were considering a historic turn away from the Cold War arms race, sentiments the president would express quite boldly just before he was killed. At a time when his generals sought a first-strike policy, Kennedy promoted a nuclear test ban treaty and offered a vision beyond the Cold War in August 1963, three months before the assassination. At the same time, Kennedy’s positions on civil rights and poverty were rapidly evolving as well. At first the Kennedys had been taken aback by the Freedom Riders, with Attorney General Robert Kennedy wondering aloud whether we had “the best interest of the country at heart” or were providing “good propaganda for America’s enemies.” [24] President Kennedy is heard on White House tapes calling the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and its chairman, future U.S. Rep. John Lewis , [25] “sons of bitches.” [26] “The problem with you people,” he once snapped, [is that] you want too much too fast.” [27] In this sense, the Kennedys were reflecting, not shaping, the mood of the country. Sixty-three percent of Americans opposed the Freedom Rides that preceded Port Huron. The New York Times opined that “nonviolence that deliberatively provokes violence is a logical contradiction.” President Kennedy, who at first opposed the March on Washington as too provocative politically, finally changed his mind and welcomed the civil rights leadership to the White House. [29]By the time of his assassination, he and his brother Bobby almost were becoming “brothers” in the eyes of the civil rights leadership. In addition to their joint destiny with the civil rights cause, President Kennedy was sparking a public interest in attacking poverty, having read and recommended Mike Harrington’s “The Other America.” One of the original plans for the War on Poverty, according to a biography of Sargent Shriver, was “empowering the poor to agitate against the local political structure for institutional reform,” which would have aligned the administration closely, perhaps too closely, with SNCC and SDS community organizers. [30]

For Kennedy truly to address poverty and racism in a second term would have required a turn away from the nuclear arms race and the budding U.S. counterinsurgency war in Vietnam. Robert Kennedy suggested as much in a 1964 interview: “For the first few years … [JFK] had to concentrate all his energies … on foreign affairs. He thought that a good deal more needed to be done domestically. The major issue was the question of civil rights…. Secondly, he thought that we really had to begin to make a major effort to deal with unemployment and the poor in the United States.” [31] Despite efforts by today’s neoconservatives to portray Kennedy as a Cold War hawk, the preponderance of evidence is that he intended to withdraw all American troops from Vietnam by 1965. Two days before his murder, for example, his administration announced plans to withdraw 1,000 to 1,300 troops from South Vietnam. But two days after his death, on Nov. 24, a covert plan was adopted in National Security Memorandum 273, which authorized secret operations, “graduated in intensity,” against North Vietnam. [32]

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy was the first of several catastrophic murders that changed all our lives, and the trajectory of events imagined at Port Huron. The dates must be kept in mind: Most of us were about 21 years old in June 1962. An idealistic social movement was exploding, winning attention from a new administration. Just as we hoped, the March on Washington made race and poverty the central moral issues facing the country and the peace movement would hear a president pledging to end the Cold War — and then a murder derailed the new national direction. I was about to turn 24 when Kennedy was killed. The experience will forever shadow the meaning of the ’60s. The very concept of a presidential assassination was completely outside my youthful expectations for the future. No matter what history may reveal about the murder, the feeling was chillingly inescapable that the sequence of the president’s actions on the Cold War and racism led shortly to his death. The subsequent assassinations of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert Kennedy in 1968 permanently derailed what remained of the hopes that were born at Port Huron. Whether one thinks the murders were conspiracies or isolated accidents, the effect was to destroy the progressive political potential of the ’60s and leave us all as “might-have-beens,” in the phrase of the late Jack Newfield.

Hope died slowly and painfully. There still was hope in the year following President Kennedy’s murder — for example, in the form of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, the most important organized embodiment of the Port Huron hope for political realignment. Organized by SNCC in 1963-64, the MFDP was a grass-roots Democratic Party led by Mississippi’s dispossessed blacks, seeking recognition from the national Democratic Party at its 1964 convention in Atlantic City. The MFDP originated in November 1963, the very month of the Kennedy assassination, when 90,000 blacks in Mississippi risked their lives to set up a “freedom vote” to protest their exclusion from the political process. Then came Freedom Summer 1964, which included the kidnapping and murders of James Cheney, Andrew Goodman and Mickey Schwerner. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover at first suggested that the missing activists had staged their own disappearance to inflame tensions, or that perhaps these three might have gotten rather fresh.” [33]

Next, just before the Democratic convention, on Aug. 2, the U.S. fabricated a provocation in the Gulf of Tonkin that expanded the Vietnam War along the lines suggested in NSM 273 (“a very delicate subject,” according to Pentagon chief Robert McNamara). [34] President Lyndon B. Johnson drafted his war declaration on Aug. 4, the same day the brutalized bodies of the three civil rights workers were found in a Mississippi swamp. On Aug. 9, at a memorial service in a burned-out church, SNCC leaders questioned why the U.S. government was declaring war on Vietnam but not on racism at home. On Aug. 20, Johnson announced the official “war on poverty” with an appropriation of less than one billion dollars while signing a military appropriation 50 times greater. [35] The war on poverty, the core of the Port Huron generation’s demand for new priorities, was dead on arrival. The theory, held by historian William Appleman Williams among others, that foreign policy crises were exploited to deflect America’s priorities away from racial and class tensions, seemed to be vindicated before our eyes.

Johnson was plotting to use the party’s leading liberals, many of them sympathetic to the fledgling SDS, to undermine the civil rights challenge from the Mississippi Freedom Democrats three weeks after the Tonkin Gulf incident. Hubert Humphrey was assigned the task, apparently to test his loyalty to Johnson before being offered the vice presidential slot. He lectured the arriving Freedom delegation that the president would “not allow that illiterate woman [an MFDP leader, Fannie Lou Hamer] to speak from the floor of the convention.” [36] Worse, the activists were battered by one of their foremost icons, the UAW’s Walter Reuther, who was flown by private jet to quell the freedom challenge; he told Humphrey and others that “we can reduce the opposition to this to a microscopic fraction so they’ll be completely unimportant.” [37] White House tapes show clearly that Johnson thought the Freedom Democrats would succeed if the matter was put to a convention vote.

This became a turning point between those who tried bringing their morality to politics, not politics to their morality, said Bob Moses, then a central figure for both SNCC and SDS. It was so intense that Humphrey broke down and cried. At one point, LBJ stole off to bed in the afternoon, vowing for 24 hours to quit the presidency. [38] The Mississippi Freedom Democrats and the hopes of the early ’60s were crushed once again, this time not by the clubs of Southern police but the hypocrisy of liberalism. If Johnson had incorporated the Mississippi Freedom delegation, we believed, he still could have defeated Barry Goldwater that November and hastened the political realignment we stood for. But the possibility of transformation evaporated. In the resulting vacuum, the first Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was born in Lowndes County, Ala., in response to the rejection of the MFDP. Only days after the convention, while Johnson was mouthing the words “no wider war,” his national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy, was suggesting that “substantial armed forces” would be sent. [39]

That fall, the Port Huron generation of SDS met in New York to ponder the options. Just two years before, the war in Vietnam seemed so remote that it barely was noted in the PHS. Some of us, following the SNCC model and convinced that realignment was underway, had moved to inner cities to begin organizing a broad coalition of the poor, under the name Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP). Others were excited about the Berkeley Free Speech Movement and prospects for campus rebellion. Still others were planning protests if the Vietnam War should escalate. Amid great apprehension, the SDS national council adopted the slogan, “Part of the Way With LBJ.” While the president vowed never to send America’s young men to fight a land war in Southeast Asia, on election day itself the plans for expanding the war were being drafted by the White House. [40] By springtime, 150,000 young American men were dispatched to war. In May, SDS led the largest antiwar protest in decades in Washington, D.C. But it was too late to stop the machine. Having learned that assassinations could change history, our generation now began to learn that official lies were packaged as campaign promises.

The utopian period of Port Huron was over, less than three years after the statement was issued. The vision would flicker on but never recover amid the time of radicalization and polarization ahead. Since the Democratic Party had failed the MFDP and launched the Vietnam War, those favoring an electoral strategy were frustrated and marginalized. Resistance grew in the form of urban insurrections, GI mutinies, draft card burnings, building takeovers and bombings. Renewed efforts at reforming the system, like the 1967-68 Eugene McCarthy presidential campaign, helped to unseat LBJ but failed to capture the Democratic nomination. RFK was the last politician who rekindled the hopes of realizing the vision of Port Huron, not only with interest in anti-poverty programs and his gradual questioning of Vietnam, but most eloquently with his 1967 speech challenging the worth of the gross national product (GNP) as a measure of well-being. I supported his candidacy, attended his funeral, and finally embraced the death of hope and the birth of rage. After Richard Nixon’s election, I was convicted with the so-called Chicago Eight of inciting a riot at the 1968 Democratic convention, a judicial process that ended in acquittal in 1972. By then, the long-awaited political realignment was partly underway, starting with Sen. George McGovern’s presidential 1972 campaign, then leading to the ascension of Southern liberals like Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Andrew Young and John Lewis to national power. But by that time it was too late to keep white Southern voters in the Democratic Party with populist economic promises. The threat to their Southern white traditions drove them into the Republican Party. It was Nixon’s strategy of realignment that prevailed. [41]

The importance of the mid-1960s turning points, however, is missed by most historians of the era, who tend to blame SDS for “choosing” to become more radical, sectarian, dogmatic and violent, as if there was no context for the evolution of our behavior. Garry Wills, whose book “Nixon Agonistes” extolled the Port Huron Statement,[42] later accused the young radicals of having prolonged the Vietnam War. [43] In his view, the movement should have practiced constructive nonviolence like Dr. King’s, an approach that aimed at gaining national acceptance. This analysis ignores the fact that Dr. King himself was becoming radicalized by 1966, and starting to despair of nonviolence. Liberal bastions like the New York Times editorially blasted him for speaking out against the Vietnam War in 1967. His murder and that of Robert Kennedy stoked violent passions among many of the young. Wills also writes that it was easier to unite Americans against the manifest evil of racism than against the Vietnam War, in which, he believes, “the establishment was not so manifestly evil.” [44] But for our generation, the fact of the U.S. government dropping more bombs on Vietnam than it did everywhere during World War II, while lying to those it was conscripting, was a manifest evil. Wills writes that the police simply “lost their heads” in Chicago, as if the beating and gassing of more than 60 journalists was somehow “provoked.” Wills complains too that his classes at Johns Hopkins were interrupted by student bomb threats, not an easy disruption to accept, but not different from the 1960 lunch-counter sit-ins that disrupted the normalcy of innocent (white) people. Wills laments that “civil disobedience had degenerated into terrorism,” [45] without acknowledging the causes or the fact that violent rebellions were taking place in both the armed forces and American ghettos and barrios at an unprecedented rate. Were the student radicals to blame for this turn toward confrontation, or was it explainable by the failure of an older generation to complete the reforms begun in the early ’60s instead of invading Vietnam? As Wills himself wrote in his 1969 book, “the generation gap is largely caused by elders who believe they have escaped it.” [46]

Similarly, some still believe that the election of Hubert Humphrey in 1968 would have ended the Vietnam War and restored liberalism as a majority coalition. Who is to say? Humphrey remains an icon for an older generation of liberals to this day. For the Port Huron generation of SDS and SNCC, however, he remains the symbol of how liberalism, driven by opportunism, chose Vietnam over the Mississippi Freedom Democrats. Whichever of these views is chosen, the forgotten fact is that Humphrey probably would have won the 1968 election if he had taken an independent antiwar stand. In late October, Nixon led 44% to 36% in voter surveys. With the election one week away, the U.S. ordered a bombing halt and offered talks. On Nov. 2, both the Gallup and Harris polls showed Nixon’s lead shaved to 42%-40%. According to historian Theodore White, “had peace become quite clear, in the last three days of the election of 1968, Hubert Humphrey would have won the election.” [47] The final result was Nixon 43.4%, Humphrey 42.7%, a margin of 0.7. Would Humphrey have ended the war? Perhaps; perhaps not. But there is no single factor that causes a loss by less than one percentage point. Anyone who magnifies the blame directed against one group or another is indulging in self-interested scapegoating. [48]

There is no doubt that many of us, myself certainly included, evolved from nonviolent direct action to acceptance of self-defense or street fighting against the police and authorities by the decade’s end. On the day the Chicago defendants were convicted, for example, there were several hundred riots in youth communities and on college campuses across the country, including the burning of a Bank of America by university students in Isla Vista, Calif. No one could have ordered this behavior; it was the spontaneous response of hundreds of thousands of young people to the perceived lack of effectiveness of either politics or nonviolence. A Gallup poll in the late ’60s showed 1 million university students identifying themselves as “revolutionary.” [49] What many fail to ask is where it all began, where the responsibility lay for causing this massive alienation among college students, inner-city residents and grunts in the U.S. military. It is convenient to accuse the teenagers and twentysomethings in the ’60s of “losing their heads,” unlike the heavily armed and professionally trained Chicago police, who knew their “riot” would be approved by their mayor. “Vietnam undid the New Left,” Wills writes, because it “blurred the original aims” of the SDS. [50] One wishes in this case that Wills had dwelt on how Vietnam undid America.

When the period we know as “the 60s” finally ended — from exhaustion, infighting, FBI counterintelligence programs [51] and, most of all, from success in ending the Vietnam War and pushing open doors to the mainstream — I turned my energies increasingly toward electoral politics, eventually serving 18 years in the California Legislature, chairing policy committees on labor, higher education, and the environment. This was not so much a “zigzag” [52] as an effort to act as an outsider on the inside. It was consistent with the original vision of Port Huron, but played itself out during a time of movement decline or exhaustion. The lessons for me were contradictory. On the one hand, there was much greater space to serve movement goals on the inside than I had imagined in 1962; one could hold press conferences, hire activist staff, call watchdog hearings with subpoena power, and occasionally pass far-reaching legislation (divestment from South Africa, anti-sweatshop guidelines, endangered-species laws, billions for conservation, etc.). Perhaps the most potent opportunities were insurgent political campaigns themselves, raising new issues in the public arena and politicizing thousands of new activists in each cycle. On the other hand, there was something impenetrable about the system of power as a whole. The state had permanent, neo-Machiavellian interests of its own, deflecting or absorbing any democratic pressures that became too threatening. The state served and brokered a wider constellation of private corporate and professional interests that expected profitable investment opportunities and law-and-order, when needed, against dissidents, radicals or the angry underclass. These undemocratic interests could reward or punish politicians through their monopoly of campaign contributions, media campaigns and, ultimately, capital flight. The absence of a multiparty system with solidly progressive electoral districts was another factor in producing compromised and centrist outcomes. I think of those two decades in elected office as an honorable interlude, carrying forward or protecting the gains of one movement while waiting for others to begin, as happened with the anti-sweatshop and anti-WTO campaigns in the late 1990s.

Next Page: The Achievements of the ’60s

Footnotes: [16]The sudden re-framing of America’s relationship with the Soviet Union was described by Cyrus Sulzberger in the New York Times thusly: “The momentum of pro-Soviet feeling worked up during the war to support the Grand Alliance had continued too heavily after the armistice. This made it difficult for the Administration to carry out the stiffer diplomatic policy required now. For this reason …a campaign was worked upto obtain a better balance of public opinion to permit the government to permit the government to adopt a harder line” (March 21, 1946). Instead of seeking coexistence with the Soviet Union, the U.S. began talk of a “cold war,” an “iron curtain,” and an “iron fist” instead of “babying the Soviets”; the Republican Party campaigned in 1946 on a platform of “Republicanism versus Communism,” and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce collaborated with the FBI in distributing anti-communist materials, all before the Chinese communist revolution or Soviet testing of an atomic bomb. See Virginia Carmichael, “Framing History, The Rosenberg Story and the Cold War,” University of Minnesota, 1993, pp. 32-33. [17]See Paul Buhle, “How Sweet It Wasn’t, The Scholars and the CIA,” in John McMillian and Paul Buhle, “The New Left Revisited,” Temple, 2003, p. 263. [18]See Todd Gitlin, “Letter to a Young Radical” … Gitlin has not moved to the conservative camp but has identified himself with “progressive patriotism,” including use of military means to quell terrorism and denunciations of street demonstrators at places like the 2004 Republican convention. Oddly, his advice to the new radicals in “Letter” omits taking a position on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. [19]Buhle, op. cited, on the Committee on Cultural Freedom. In 1967, Ramparts magazine exposed the longtime CIA funding of the U.S. National Student Association. The CIA and the State Departments have long provided funding for international AFL-CIO projects designed to subvert radical labor movements in Latin America and elsewhere. According to Senate hearings held by Sen. Frank Church, the CIA funded several hundred academics on more than 200 campuses to “write books and other material to be used for propaganda purposes.” See Zinn, pp. 555-556. [20]For my own account, see Hayden, “Rebel,” p. 79-84; or Gitlin, op. cited, 113-126. [21]See Lori Wallach and Patrick Woodall, “Whose Trade Organization?, A Comprehensive Guide to the WTO,” The New Press, 2004. [22]The portion of America’s gross national income given in foreign aid has declined by nearly 90% since the time of the Port Huron Statement, from 0.54% in 1962 to 0.16% in 2004, ranking the U.S. government behind 20 other nations (N.Y. Times, April 18, 2005). [23]Recent victims of the “soft on terrorism” charge were U.S. Sen. Max Cleland, a paraplegic Vietnam veteran, in 2002, and of course U.S. Sen. and decorated Vietnam War hero John Kerry in the 2004 presidential race. [24]Taylor Branch, “Pillar of Fire,” 1998, pp. 475-476 [25]At the time Lewis was the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the most radical and front-line civil rights organization. Attempts were made to edit and dilute his speech given at the March on Washington, which asked a good question, “Where is our party?” Later Lewis became an elected Atlanta congressman and prime sponsor of the Smithsonian’s African-American Museum, near the spot where the 1963 march took place. [26]Rosenberg and Karabell, p. 172 [27]Jonathan Rosenberg and Zachary Karabell, “Kennedy, Johnson, and the Quest for Justice, The Civil Rights Tapes,” Norton, 2003, p. 31 [28].Sixty Three Percent Disapproval of Freedom Rides in Taylor Branch “Parting the Waters, America in the King Years, 1956-63,” Simon and Shuster, 1988, p. 478. New York Times editorial, Branch, p. 478 as well. [29]Rosenberg and Karabell, p. 130 [30]Scott Stossel, “Sarge, The Life and Times of Sargent Shriver,” Smithsonian, 2004, p. 476 [31]Edwin Guthman and Jeffrey Shulman, “Robert Kennedy in his Own Words,” Bantam, 1988, p. 300 [32]Richard Parker, “John Kenneth Galbraith, His Life, His Economics, His Politics,” Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 2005, p. 405. James K. Galbraith, “Exit Strategy,” New York Review of Books, October/November 1963. Robert McNamara confirmed Kennedy’s plan for a complete withdrawal by 1965 in a speech at the LBJ Library on May 1, 1995, based on White House tapes. On Oct. 4, 1963, a memorandum from Gen. Maxwell Taylor stated that “All planning will be directed towards preparing RVN forces for the withdrawal of all US special assistance units and personnel by the end of calendar year 1965.” In a conversation with Daniel Ellsberg, Robert Kennedy stated that “We wanted to win if we could, but my brother was determined never to send ground troops to Vietnam…. I do know what he intended. All I can say is that he was absolutely determined not to send ground units…. We would have fuzzed it up. We would have gotten a government that asked us out or that would have negotiated with the other side. We would have handled it like Laos.” Ellsberg, Secrets, Viking, 2002, p. 195. In an earlier, more ambiguous interview in 1964, while he was mulling his own thoughts about Vietnam, RFK gave noncommittal answers to John Barlow Martin: “Q: There was never any consideration given to pulling out? A: No. Q: But at the same time, no disposition to go in — A: No…. Everybody, including Gen. MacArthur, felt that land conflict between our troops — white troops and Asian — would only end disaster.” Robert F. Kennedy in his own words, “The Unpublished Recollections of the Kennedy Years,” Bantam, 1988, p. 395. On these issues, I disagree with Noam Chomsky and numerous others who have claimed that LBJ’s escalation of the war was simply a “continuation of Kennedy’s policy,” to quote Stanley Karnow as cited in Galbraith. [33]Michael R. Beschloss, “Taking Charge, The Johnson White House Tapes, 1963-64,” Simon and Schuster, 1997, p. 439[34] Beschloss, p. 508 [35]Beschloss, p. 455. [36]According to SNCC participants in the meeting. [37]Beschloss, p. 534. [38]Beschloss, p. 532-33 [39]Beschloss, p. 546. [40]According to Daniel Ellsberg, then at the Pentagon, an interagency task was set up by the president the day before the Nov. 3 election to make plans for escalation. “It hadn’t started a week earlier because its focus might have leaked to the voters…. Moreover, we didn’t start the work a day or week later, after the votes were cast, because there was no time to waste…. It didn’t matter that much to us what the public thought.” Daniel Ellsberg, “Secrets, A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers,” Viking, 2002, pp. 50-51. [41]See Kevin Phillips, “The Coming Republican Majority” (1968) [42]Garry Wills, “Nixon Agonistes,” Signet, 1969, pp. 327-333 [43]Garry Wills, “A Necessary Evil, A History of American Distrust of Government,” Simon and Schuster, 1999, pp. 289-298 [44]Garry Wills, “A Necessary Evil,” Simon and Schuster, 1999, p. 293. [45]Wills, p. 293. [46]Wills, “Nixon Agonistes,” p. 301. [47]Hayden, “Rebel,” p. 299 [48]In 2000, by comparison, I campaigned for Al Gore over the third-party campaign of Ralph Nader. [49] Sale, p [50]Wills, p. 294 [51]Many of us were targeted for “neutralization” by the FBI. See “Rebel” for FBI documents. For declassified FBI counterintelligence documents against dissenters over the years, see Ward Churchill, Jim Vander Wall, “The Cointelpro Papers,” South End, 1990, 2002. [52]The “zigzag” accusation is from Berman, p. 109. The Achievements of the ’60s

SDS could not survive the decade as an organization. In part, the very ethos of participatory democracy conflicted with the goal, shared by some at Port Huron, of building a permanent New Left organization. Not only was there a yearly turnover of the campus population, but SDS activists were committed in principle to leave the organization in two or three years to make room for new leadership. Meanwhile, it seemed that new radical movements were exploding everywhere, straining the capacity of any single organization like SDS to define, much less coordinate, the whole. Administrators, police and intelligence agencies alternated among strategies of co-optation, counterintelligence and coercion. SDS disintegrated into rival Marxist sects that had been unimaginable to us in 1962, and those groups devoured the host organization by 1969. (I would argue that one of them, the Weather Underground, was an authentic descendent of the Port Huron generation, rebelling against the failure of our perceived reformism.)

But it would be a fundamental mistake to judge the participatory ’60s through any organizational history. SDS, following SNCC, was a catalytic organization, not a bureaucratic one. The two groups catalyzed more social change in their seven-year life spans than many respectable and well-funded nongovernmental organizations accomplish in decades. [53] If anything, the ’60s were a triumph for the notions of decentralized democratic movements championed in the Port Huron Statement. Slogans like “Let the people decide” were heartfelt. The powerful dynamics of the ’60s could not have been “harnessed” by any single structure; instead the heartbeat was expressed through countless innovative grass-roots networks that rose or fell based on voluntary initiative. The result was a vast change in public attitudes as the ’60s became mainstreamed.

In this perspective, the movement outlived its organized forms, like SDS. Once any organizational process became dysfunctional (national SDS meetings began drawing 3,000 participants, for example), the movement energy flowed around the structural blockages, leaving the organizational shell for the squabbling factions. For example, in the very year that SDS collapsed, there were millions in the streets for the Vietnam Moratorium and the first Earth Day. In the first six months of 1969, based on information from only 232 of America’s 2,000 campuses, over 200,000 students were involved in protests, 3,652 had been arrested, and 956 suspended or expelled. In 1969-70, according to the FBI, 313 building occupations took place. In Vietnam, there were 209 “fraggings” by soldiers in 1970 alone. Public opinion had shifted from 61% supporting the Vietnam War in 1965 to 61% declaring the war was wrong in 1971. [54] The goals of the early SDS were receiving majority support while the organization was becoming too fragmented to benefit.

When a movement declines, no organization can resuscitate it. This is not to reject the crucial importance of organizing, or the organizer’s mentality, or the construction of a “civil society” of countless networks. But it is to suggest a key difference between movements and institutions. The measure of an era is not taken in membership cards or election results alone, but in the changes in consciousness, in the changing norms of everyday life, and in the public policies that result from movement impacts on the mainstream. Much of what we take for granted — voting by renters, a five-day workweek, clean drinking water, the First Amendment, collective bargaining, interracial relationships – is the result of bitter struggles by radical movements of yesteryear to legitimate what previously was considered antisocial or criminal. In this sense, the effects of movements envisioned at Port Huron, and the backlash against them, are deep, ongoing and still contested.

First, American democracy indeed became more participatory as a result of the ’60s. More constituencies gained a voice and a public role than ever before. The political process became more open. Repressive mechanisms were exposed and curbed. The culture as a whole became more tolerant.

Second, there were structural or institutional changes that redistributed political access and power. Jim Crow segregation was ended in the South, and 20 million black people won the vote. The 18-year-old vote enfranchised an additional 10 million young people. Affirmative action for women and people of color broadened opportunities in education, the political process and the workplace. The opening of presidential primaries empowered millions of voters to choose their candidates. New checks and balances were imposed on an imperial presidency. Two presidents, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, were forced from office.

Third, new issues and constituencies were recognized in public policy: voting rights acts, the clean air and water acts, the endangered-species laws, the Environmental Protection Agency, the occupational health and safety acts, consumer safety laws, non-discrimination and affirmative action initiatives, the disability rights movement, and others. A rainbow of identity movements, including the American Indian Movement (AIM), the Black Panther Party and the Young Lords Party, staked out independent identities and broadened the public discourse.

Fourth, the Vietnam War was ended and the Cold War model was challenged. Under public pressure, Congress eliminated military funding for South Vietnam and Cambodia. The Watergate scandal, which arose from Nixon’s repression of antiwar voices, led to a presidential resignation. The U.S. ended the military draft. The Carter administration provided amnesty for Vietnam-era deserters. Beginning with Vietnam and Chile, human rights was established as an integral part of national security policy. Relations with Vietnam were normalized under the leadership of President Bill Clinton, a former McCarthy and McGovern activist, and Sen. John Kerry, a former leader of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. [55]

Fifth, the ’60s consciousness gave birth to new technologies, including the personal computer. I remember seeing my first computer as a graduate student at the University of Michigan in 1963; it seemed as large as a room, and my faculty adviser, himself a campus radical, promised that all our communications would become radically decentralized with computers the size of my hand. “It is not a coincidence,” writes an industry analyst, “that, during the 60’s and early 70’s, at the height of the protest against the war in Vietnam, the civil rights movement and widespread experimentation with psychedelic drugs, personal computing emerged from a handful of government- and corporate-funded laboratories, as well as from the work of a small group…[who] were fans of LSD, draft resisters, commune sympathizers and, to put it bluntly, long-haired hippie freaks.” [56] While it is fair to say the dream of technology failed, there is no doubt that the Internet has propelled communication and solidarity among global protest movements as never before, resulting in a more participatory, decentralized democratic process.

The ’60s, however, are far from over. Coinciding with their progressive impacts has been a constant and rising backlash to limit, if not roll back, the social, racial, environmental and political reforms of the era. Former President Clinton, an astute observer of our political culture, says that the ’60s remain the basic fault line running through American politics to this day, and the best measure of whether one is a Democrat or a Republican. It is important to note that the ’60s revolt was a global phenomenon, producing a lasting “generation of ’68,” sharing power in many countries including Germany, France, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Northern Ireland, South Africa and South Korea, to name only a few.

Social movements begin and end in memory. The fact that we called ourselves a “new” left meant that our radical roots largely had been severed, by McCarthyism and the Cold War, so that the project of building an alternative was commencing all over again. Social movements shift from the mysterious margins to the mainstream, become majorities, then are subject to crucial arguments over memory. The ’60s are still contested terrain in schools, the media and politics, precisely because the recovery of their meaning is important to social movements of the future and the suppression or distortion of that memory is vital to the conservative agenda. We are nearing the 50th anniversary of every significant development of the ’60s, including the Port Huron Statement. The final stage of the ’60s, the stage of memory and museums, is underway.

Next Page: Students, the Universities and the Postmodern Legacy

Footnotes: [53]One exemption to this rule is the National Organization for Women (NOW), which has managed to balance the catalytic and bureaucratic poles since its inception in 1965. Another is the Sierra Club. In both cases, the grass-roots membership plays a key role in the energy flow through the organizational machinery. [54]All figures in Zinn, pp. 490-492. [55]The then-secret Pentagon Papers quote administration advisers in 1968 as saying “this growing disaffection accompanied as it certainly will be, by increased defiance of the draft and growing unrest in the cities because of the belief that we are neglecting domestic problems, runs great risks of provoking a domestic crisis of unprecedented proportions.” In his memoirs, President Nixon wrote that “although publicly I continued to ignore the raging antiwar controversy … I knew, however, that after all the protests and the Moratorium, American public opinion would be seriously divided by the war.” Note that these concerns were based purely on cost/benefit calculations, not on moral or public policy grounds. In Zinn, pp. 500, 501. [56]John Markoff, “What the Dormouse Said, How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry,” Viking, 2005. See New York Times review, May 7, 2005. Students, the Universities and the Postmodern Legacy

Of all the contributions of the Port Huron Statement, perhaps the most important was the insight that university communities had a role in social change. Universities had become as indispensable to economics in what we called the automation age as factories were in the age of industrial development. Robert McNamara, after all, was trained at the University of Michigan. In a few years, University of California President Clark Kerr would invent the label “multiversity” to explain the importance of knowledge to power.

Clearly, the CIA understood the importance of universities; as early as 1961, as the Port Huron Statement was being conceived, its chief of covert action wrote that books were “the most important weapon of strategic propaganda.” [57]

We saw the possibilities, therefore, in challenging or disrupting the role of the universities in the knowledge economy. More important, however, was the alienation that the impersonal mass universities bred among idealistic youth searching for “relevance,” as described in some of the most eloquent passages of the Port Huron Statement. We wanted participatory education in our participatory democracy, truth from the bottom up, access for the historically excluded to the colleges and universities. Gradually, this led to a fundamental rejection of the narratives we had been taught, the myths of the American melting pot, the privileged superiority of (white) Western civilization, and inevitably to the quest for inclusion of “the other” — the contributions of women, people of color and all those marginalized by the march of power. The result of this subversion of traditional authority became known as multiculturalism, deconstruction and postmodernism. In his perceptive 1968 study, “Young Radicals, Notes on Committed Youth,” the Harvard researcher Kenneth Kenniston was the first to conclude that our “approach to the world — fluid, personalistic, anti-technological, and non-violent — suggests the emergence of what I will call the post-modern style.” [58] It could also be called the Port Huron style, the endless improvising, the techniques of dialogue and participation, learning through direct action, the rejection of dogma while searching for theory. It was typical of the style that the PHS was offered as a “living document,” not a set of marching orders.

When I first met Howard Zinn, he was a professor at a black women’s college in Atlanta, where both of us were immersed in the early civil rights movement. He was one of the few engaged intellectuals I had ever met. While witnessing and participating in the civil rights movement, he was discovering a “story” far different than the conventional one he knew as a trained historian. It eventually was published as “A People’s History of the United States,” selling some 750,000 copies although Zinn was fired by two universities.

Thanks to Zinn and numerous subsequent writers, the “disappeared” of history were suddenly appearing in new narratives and publications developed in ethnic studies, women’s studies, African-American studies, Chicano studies, queer studies, environmental studies. Films like “Roots,” “The Color Purple” and “Taxi Driver” expanded and deepened this discovery process. Conservatives like Lynn Cheney, wife of Vice President Dick Cheney, were distressed that more young people knew of Harriet Tubman than the name of the commandeer of the American revolutionary army (George Washington). [59]

Cheney has been working since the Reagan era to undercut the ’60s cultural revolution, but the effort is not simply Republican. Among the corporate Democrats, Larry Summers, former Treasury secretary and now president of Harvard, is devoted to “eradicating the influence of the 1960s,” according to a recent biography (Richard Bradley, “Harvard Rules,” HarperCollins, 2005; quoted in New York Times review, March 27, 2005).

The unexpected student revolt that produced the Port Huron Statement was the kind of moment described by the French philosopher of deconstruction, Jacques Derrida, who took the side of the French students at the barricades in 1968. In his words, Derrida tried to “distinguish between what one calls the future and ‘l’avenir’. There’s a future that is predictable, programmed, scheduled, foreseeable. But there is a future, l’avenir (to come), which refers to someone who comes whose arrival is totally unexpected. For me, that is the real future. That which is totally unpredictable. The Other who comes without my being able to anticipate its arrival. So if there is a real future beyond this other known future, it’s l’avenir in that it’s the coming of the Other when I am completely unable to foresee its arrival.” [60]

The Port Huron Statement announced such an unexpected arrival, with a simple introductory sentence: “We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably at the world we inherit.” Now as that same Port Huron generation enters into its senior years, it’s worth asking whether we are uncomfortable about the world we are passing on as inheritance, and what may still be done. For me, the experience of the ’60s will always hold a bittersweet quality, and I remain haunted by another question raised by Ignazio Silone in “Bread and Wine”: “What would happen if men remained loyal to the ideals of their youth?”[61]

Now that deconstruction has succeeded, is it time for reconstruction again? The postmodern cannot be an end state, only a transition to the unexpected future. Transition to what? Not an empire, not a fundamentalist retreat from modernity, for they are no answers to the world crisis. As the Port Huron Statement said, “The world is in transition. But America is not.” New global movements, symbolized by the 1999 Seattle protests against the World Trade Organization, declare that “another world is possible,” echoing the Zapatista call for “a world in which all worlds fit.” The demands of these new rebels are transitional too, toward a new inclusive narrative in addition to the many narratives of multiculturalism. Perhaps the work begun at Port Huron will be taken up again, this time around the world, for the globalization of power and capital and empire surely will globalize the stirrings of conscience and resistance. While the powers that be debate whether the world is dominated by a single superpower (the U.S. position) or is multipolar (the position of the French, the Chinese and others), there is an alternative vision appearing among the millions involved in global justice, peace, human rights and environmental movements, a future created through participatory democracy.

Footnotes: [57] From Senate hearings, in Zinn, 557. At the time, in 1961, I was writing a pamphlet on the civil rights movement for the U.S. National Student Association, for international distribution. Without my knowledge, CIA funds were paying for it, presumably to show an idealistic image at international youth forums. [58]Kenneth Kenniston, “Young Radicals, Notes on Committed Youth,” Harcourt Brace, 1968, p. 235. [59]Lynn Cheney [60] Kirby Dick and Amy Kofman, “Derrida,” Routledge 2005, p. 62[61]Silone, p. 146

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.