Larry Gross: Abe Rosenthal’s Reign of Homophobia at The New York Times

Former New York Times Executive Editor Abe Rosenthal, who died this month, was a raging homophobe--a failing that proved tragic when the AIDS crisis erupted on his watch. Gay and lesbian studies pioneer Larry Gross explores what happened when America's paper of record ignored one of the major civil rights stories of our time.

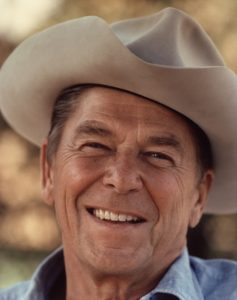

The death of former New York Times Executive Editor Abe Rosenthal on May 10 was front-page news, and not only in The New York Times. One of the dominant figures in journalism in the late 20th century when newspapers were still a force to be reckoned with and the Internet wasn’t even a gleam in anyone’s eye, Rosenthal’s finest hour was the epic 1971 battle with the Nixon White House over the publication of the Pentagon Papers. However, there is a side to Abe Rosenthal that was not noted in the obituaries and recollections splashed across many inches of newsprint.

The New York Times is not just another newspaper. In the words of former Times columnist Sydney Schanberg, it is “the newspaper that interprets the establishment to the establishment; that tells the establishment what it is doing and how it should be done.” The immense power of the Times generally has made the paper fairly slow to notice or respond to changes in society, as the paper seems to feel it has a responsibility to serve as a brake rather than a locomotive. At least this was the case in the 1960s as gay people began to become more visible in American society. The Times’ well-known motto is “All the news that’s fit to print,” and for a long time it was clear that gay people’s stories were unfit.

The news media are well known for not having clearly stated rules of procedure, but rather relying on an instinct known as “news judgment” — knowing what is and is not a “story,” whether a story deserves front-page or back-page placement, and how a story should be presented. In fact, of course, there are rules. Some are written down in the guidelines that most media organizations maintain, but the most important rules are those learned by editors and reporters by observing what happens when someone breaks one. Such critical incidents provide everyone in a news organization with dramatic evidence that an unwritten rule exists and must be observed, and it was in this way that editors and reporters at The New York Times learned that the topic of homosexuality was not popular with the higher-ups.

In 1975 the Sunday travel section ran an article that was certainly unusual for The New York Times. Not only was the piece open about sexuality in a fashion that was not typical of the Times — the paper did not print the word “penis” until 1976, when it appeared in a Personal Health column about impotence — but the sexuality the article was open about was homosexuality. The story was called “The All-Gay Cruise: Prejudice and Pride,” by a free-lancer named Cliff Jahr, and it described a weeklong ocean cruise taken by 300 gay men and lesbians. The article was hip and sexy in a most un-Times-like fashion — Jahr quotes one man as boasting, “I’ve met three Mister Rights before lunch.” It was also imbued with an awareness of the gay experience, noting that the cruise gave the passengers a respite from the oppression of closeted lives.

Publisher Arthur Sulzberger was furious. According to some accounts, travel section editor Robert Stock and Sunday editor Max Frankel were nearly fired over the incident. Another person who was angered by the piece was then managing editor Abe Rosenthal, whose reign as executive editor was to last from 1977 to 1986.

As Rosenthal ascended to the top of the Times ladder, his prejudices defined the unspoken but nevertheless unmistakable rules for deciding what was fit to print. As journalist and writer Charles Kaiser, who worked at the Times under Rosenthal, put it, “Everyone below Rosenthal spent all of their time trying to figure out what to do to cater to his prejudices. One of these widely perceived prejudices was Abe’s homophobia. So editors throughout the paper would keep stories concerning gays out of the paper.”

One such story happened in November 1980, when a homophobic gunman went on a rampage in Greenwich Village, killing two gay men and wounding seven others with machine-gun fire. The story was front-page news in the Post and the Daily News but not in the New York Times. The metropolitan editor knew Rosenthal’s feelings about gays and knew, as he later said, that “you had to be careful with the subject.”

Abe Rosenthal’s homophobia was felt at the Times in two ways: It ensured that lesbian and gay reporters stayed firmly in the closet, and that the word “gay” was not used in the paper to describe gay people. The furor over the travel section article was the critical incident inscribed in the paper’s unwritten rule book. As Jeff Schmalz, a Times editor, later recalled, “There was a lot of shouting about it. Abe thought it was a mistake and that we never should have done it. And we’d used the word ‘gay.’ He said we could never use that word again.” And, for the most part they didn’t. The word crept into news stories and headlines from time to time, but the paper’s official policy ruled the word “gay” out of order, while at the same time the gay liberation movement was exploding all around it. Rosenthal was not limited in his biases to anti-gay prejudice — he also refused to allow the word “Ms.” to be used until 1986 — but his homophobia proved tragic when the AIDS crisis erupted on his watch.

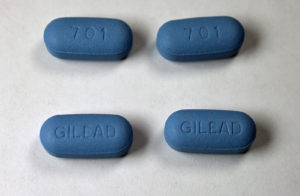

As the AIDS epidemic began to emerge, the silence of the media in general, and of The New York Times in particular, contributed to the magnitude of the unfolding tragedy. Although the death toll mounted in the early 1980s, the Times maintained a disdainful distance. As gay journalist Michelangelo Signorile put it, “Rosenthal, who attacks anti-Semitism in the media, never realized that the way he was treating the AIDS epidemic wasn’t much different from the way that news organizations treated the Holocaust early on.”

Ironically, the media blackout that broke the patience of many gay activists was not the report of a medical breakthrough but a fundraiser. In April 1983 the Gay Men’s Health Crisis arranged a circus benefit that sold out Madison Square Garden, filling it with 18,000 lesbians, gay man and others. The arena was not only jampacked; it was star-studded: Leonard Bernstein led “The Star Spangled Banner.” The event was covered by television and the newspapers, but not The New York Times.

A group of lesbian and gay activists wrote to the publisher demanding a meeting and was offered an “off the record” meeting with a Times vice president. The meeting was not successful in obtaining changes in policy, but it did result in a second meeting, this time with Executive Editor Rosenthal. Rosenthal admitted that not covering the circus benefit had been a mistake, and even agreed that the paper should do more to cover AIDS. But he was unwilling to budge on the use of the word “gay” or to move very far in any direction toward meeting the demands of the lesbian and gay community. Yet even this small opening permitted some fresh air to penetrate the Times’ closeted atmosphere, and several people from the paper called to thank the activists for their efforts. The real changes at the Times did not come until there was a changing of the guard on 43rd Street.

As journalist Sam Anson later put it, “the relief that swept through the newsroom the morning of October 16, 1986, was palpable, almost giddy.” Abe Rosenthal had reached the mandatory retirement age of 65, and was replaced as executive editor by Max Frankel. Rosenthal’s reign was described by many as a period of paranoia and terror at the Times — one reporter said, “He was like the czar; people would get gulaged at the drop of a hat.” But if the feeling of relief was general, it was especially felt by lesbian and gay employees. Frankel lost little time in letting people know that times had indeed changed, and that included the paper’s attitudes toward gay people and stories affecting them.

One of the first areas in which Frankel’s piloting of the Times became apparent was the coverage of AIDS. Within a few months of his taking over, the paper published its first serious articles on the impact of AIDS on New York–a four-part series, each installment of which began on the front page. Within a year a media writer for the Los Angeles Times quoted medical authorities and other journalists as rating the New York Times AIDS coverage as some of the best then appearing anywhere.

In the summer of 1987 Frankel made a second major change by authorizing a memo from the managing editor: “Starting immediately, we will accept the word ‘gay’ as an adjective meaning homosexual, in references to social or cultural patterns and political issues.” According to a former Times staffer, Frankel sent a memo to publisher Sulzberger, “Punch, you’re going to have to swallow hard on this one: We’re going to start using the word gay.” Frankel was aware of the impact this change would have on the morale of the lesbian and gay employees at the paper — “I knew they’d had a hard time, and I knew they weren’t comfortable identifying themselves as gay” — but he may not have been aware of the extent to which the change signaled the start of a new era in the Times’ coverage of gay issues.

In reporting on Abe Rosenthal’s funeral on May 14, James Barron wrote that William Safire, a former Op-Ed columnist who writes the “On Language” column for The New York Times Magazine, noted that Rosenthal had often said that he wanted his epitaph to be, “He kept the paper straight.”

Damn straight.

Larry Gross is the director of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and is a pioneer in the field of gay and lesbian studies.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.