The Cutting Edge of Backward Thinking

Senate Republicans are determined to join with the Supreme Court to keep women on the losing end of discriminatory pay.WASHINGTON — When you conjure up a mental image of modernity, the Senate cloakroom doesn’t come quickly to mind. Still, you would think the guys who run the place — as of now there are only 16 female senators — would get it. They don’t.

There is no other way to explain Senate Republicans’ obstinate refusal to allow women to sue for pay discrimination under rules that were in place for years. That is, years before a five-man majority on the U.S. Supreme Court decided only last year to set the bar higher — in essence, impossibly high — for a woman to bring a successful suit over discriminatory pay.

The point in contention last week was whether the Senate would allow a vote on a measure to restore what had been the practice before the Supreme Court took the case of Lilly Ledbetter, a former Goodyear Tire and Rubber plant supervisor from Alabama, and used it to turn settled discrimination law on its head. Before the Ledbetter decision, discriminatory pay lawsuits could be brought on the premise that each and every paycheck was a violation. The high court reversed this principle, stating that a victim had to bring suit only at the time a first discriminatory decision is made — and if that was a decade or two earlier, and she had no way to know about it — well then, tough luck.

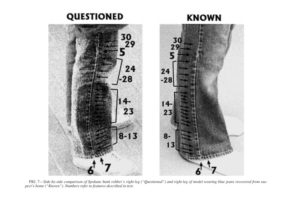

The best outline of how this all works is in Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s dissent, which discussed how Ledbetter was unaware of the accumulating disparity between her pay and that of male managers doing the same work. “Initially, Ledbetter’s salary was in line with the salaries of men performing substantially similar work,” Ginsburg wrote. “Over time, however, her pay slipped in comparison to the pay of male area managers with equal or less seniority. By the end of 1997, Ledbetter was the only woman working as an area manager and the pay discrepancy between Ledbetter and her 15 male counterparts was stark: Ledbetter was paid $3,727 per month; the lowest paid male area manager received $4,286 per month, the highest paid, $5,236.”

What’s more, Ginsburg notes, Ledbetter had proved to a jury that her lower pay was due to “a long series of decisions” reflecting Goodyear’s “pervasive discrimination against women managers in general and Ledbetter in particular.” At one point, Ledbetter’s pay had fallen below that of Goodyear’s minimum threshold for her position. Yet under the high court’s May 2007 decision, the discrimination Ledbetter proved to a jury is “not redressable” under the law because she did not file a lawsuit after the initial decision to pay her an illegally low wage.

This is how Senate Republicans want the workplace to be for American women.

They used a filibuster to block action on a measure that would have counteracted the Supreme Court ruling. They acted in concert with the White House, which threatened to veto the measure, and of course, with the usual lineup of GOP-friendly business groups that saw in the Supreme Court decision an opening and took it.

And what of John McCain, the presumed Republican standard-bearer? He proved to be as ignorant about pay discrimination as he once professed to be about the economy. It’s not just that he refused to leave the campaign trail in order to vote. It was worse. What women need, McCain offered, is more “education and training.”

Ledbetter did not lack for either. She was paid less — far less — than the men who did precisely the same job.

Nor does McCain’s analysis bear any resemblance to pay statistics compiled by the government. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women who work full time are paid less than men in just about every job category: As lawyers, computer software engineers and chemists, women are paid less than their male counterparts. Women file clerks are paid less than men in that job, and yes, so are female butchers and bakers. So much for the education-and-training argument.

The Democrats are in the midst of a presidential campaign in which much hot air has been blown — usually by male commentators and often with undisguised disdain — about whether or not Hillary Clinton should ever play what they call the “gender card.” The aftermath of the Ledbetter case provides the glimpse of an answer: The powers that be are quite content to keep dealing American women a bad hand.

Marie Cocco’s e-mail address is mariecocco(at)washpost.com.

© 2008, Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.