Jane Ciabattari on the Delights of the Rural Life

Is the pastoral arcadia of the country life far from derivatives and emissions and the other excreta of our modern cities all that it's cracked up to be? Two new memoirs give readers who don't want to stir from their armchairs to take up farming an insider's look.

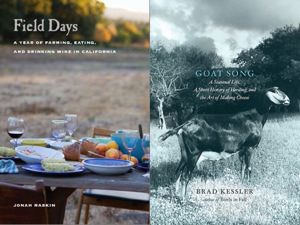

As Alice Waters hovers in the wings as a muse for the Obama era, inspiring the White House garden and healthy school lunches, the fantasy of a pastoral life far from derivatives and emissions and other excreta of our times abounds. Right on track are these two memoirs — journalist Jonah Raskin’s “Field Days: A Year of Farming, Eating, and Drinking Wine in California,” an account of organic farming in Sonoma County, and novelist Brad Kessler’s “Goat Song: A Seasonal Life, a Short History of Herding, and the Art of Making Cheese,” a chronicle of learning to raise goats and make cheese on a farm in Vermont. Each provides vicarious and delicious adventures for those of us more likely to buy locally at farm stands or plant a garden patch than respond to the call of the land at full bore.

In the process of writing these memoirs, both Raskin and Kessler made drastic shifts in daily routine, and followed an imperative to digest a universe of new information, much of it nonverbal. Paramount for each was a personal quest — for healthier living, for connection to the land, for simplicity — or, possibly, simply for peace and quiet.

Field Days

By Jonah Raskin

University of California Press, 344 pages

Goat Song

By Brad Kessler

Scribner, 256 pages

Raskin, author of “The Radical Jack London” and “American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ and the Making of the Beat Generation,” sketches Northern California’s organic farming lineage quickly, beginning with Jack and Charmian London, who settled in Sonoma’s legendary Valley of the Moon in 1906 and grew much of their own food. He includes Warren Weber of Marin County’s Star Route Farm, and makes it clear that Sonoma County’s farms have supplied Alice Waters’ restaurant kitchen for decades and impressed Carlo Petrini, founder of the Slow Food movement.

“Field Days” begins as a search for “the perfect farm,” and is in some ways a meandering, a gathering of facts to fill a reporter’s notebook (numbers of acres in organic farming in California, an on-the-ground update of the state of farmworkers’ rights, a survey of organic farms and wineries in Northern California). When Raskin finds Oak Hill Farm, the pace quickens. “ … Even at first sight I felt a sense of being enclosed and protected within the Oak Hill world that surrounded me, and I wanted to embrace it in return.” He has found what he calls the “hero” of his book. Filling in the profile of Oak Hill Farm becomes the centerpiece of his labors. As it turns out, he mentions offhandedly, this is hallowed literary ground, with legendary food writer M.F.K. Fisher’s house within view.

Through July and August, Raskin spends his days laboring in the fields at Oak Hill Farm. The work is transforming. At day’s end, he writes, “I felt exhilarated and clean at the core of my being. … I felt younger and more energetic, and I developed a deeper connection to the earth and a more meaningful sense of place than I had had for years. In the 1950s, when suburbia came to Long Island, I felt displaced. Now, in the Valley of the Moon, I felt reattached to the earth and infused with a new appreciation for the land and the soil. Belonging was uplifting.”

Day by day Raskin learns techniques taught by the fieldworker pros — gently dropping baby leeks in bunches of three into rows 18 inches apart, harvesting raspberries and melons, learning to use a wheel hoe to plant cauliflower and cabbage, cutting flowers. (“I learned to know what made a bouquet by touch and a sense of beauty beyond calculation. … I had the feeling of being in a picture; here, again, was an aesthetic experience of the kind I wanted. Diego Rivera, who loved to paint flowers, might have captured these sunflowers … on one of his canvases.”)

He is sumptuously specific as he describes the pure physical pleasures of the harvest. At one point he prepares a dinner of tomato soup from tomatoes he’d picked and roasted with basil and olive oil, Oak Hill corn on the cob, a whole chicken with tarragon, with Oak Hill red and yellow peppers. Another evening, at Tierra farm, the executive chef from Millennium restaurant serves a black bean and smoked onion torte, a ragout of Tierra’s beans, soft polenta with chipotle-glazed beets, pumpkin crostata with white pumpkin mousse.In the fall, Raskin writes, “Apples ripened in abundance, and all the other fall fruits tumbled down too: pomegranates, persimmons, and pears, all of which I ate profusely, with Fanny’s Café Granola, or with blue cheese from the Cowgirl Creamery, or all by themselves.” “Field Days” is a skeptic’s journey, making its discoveries all the more potent.

Kessler, author of the moving novel “Birds in Fall,” which begins when a plane falls from the sky off the coast of a remote island in Nova Scotia, is a recipient of the Rome Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Whiting Writers’ Award.

“Goat Song” is, Kessler writes, the story of his first years with dairy goats. “A story about what it’s like to live with animals who directly feed you. I tell of cheese and culture and agriculture, but also of the rediscovery of a pastoral life.” We have forgotten how much of everyday culture derives from a lifestyle of herding hoofed animals, he writes, “from our alphabet to our diet to elements of our economy and poetry.”

Field Days

By Jonah Raskin

University of California Press, 344 pages

Goat Song

By Brad Kessler

Scribner, 256 pages

“Goat Song” also is a novelist’s revel, replete with goat sex (yes, graphic descriptions), birth, milking, weaning, herding, and the complex and yeasty process of making cheese from the raw milk of the goats you milk. This memoir impresses most when Kessler records the quotidian in all its mystery and beauty. He records in lyrical terms his sheer love of being in the company of his herd, and moments of sheer hedonism. The first taste of his own home-made fresh chevre, for instance.

“It tasted like nothing we’d ever eaten before — a custard, a creamy pudding, the cheese so young and floral it held within its curd the taste of the grass and herbs the goat had been eating the day before. It seemed we were eating not a cheese, but a meadow.”

Later, he and his wife sample three small cakes of his initial attempts at aged chevre, the first covered with chives, the second with pepper. “Then we unmolded a third and poured a pool of honey over the cake and ate it like a dessert, with spoons.”

Kessler turns serious about his cheese-making. He travels to the Ferme de Rouze in the Pyrenees, a village whose terroir seems most compatible with his flinty Vermont location, and studies with a French master who gives him the protocol, step by step. As he leaves, he writes, “I knew at last what kind of cheese I’d make back in Vermont … a cheese made from goats and clouds, humility and mountain air.”

By book’s end, he takes a sample of his handcrafted cheese into an artisanal restaurant in New York, where the fromager declares it “herbaceous,” “grassy,” “very good.” (The East Coast equivalent of the San Francisco menu’s notation: “Oak Hill’s mixed heirloom tomatoes with queso fresco.”)

In these fresh, impassioned reports from the fields, Raskin and Kessler remind us that the farming renaissance has been rooting in this country for decades. Indeed, the connection between humans and growing things — plants, animals — is a bedrock we ignore at our peril. Their explorations, eloquently reported, remind us, too, of the simple pleasures of growing things, of herding, of re-entering the natural landscape so thoroughly that human concerns regain their proper scale.

|

Jane Ciabattari’s reviews and interviews have appeared in The Guardian online, Bookforum, The New York Times, The Daily Beast, the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, The Washington Post and the Columbia Journalism Review, among other publications. She is president of the National Book Critics Circle. |

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.