Arnold Mesches’ Death Closes a Chapter on Socially Conscious Art in American History

Throughout his long and distinguished career, the artist used his talent to provide incisive visual commentary about the major social and political issues of his time.

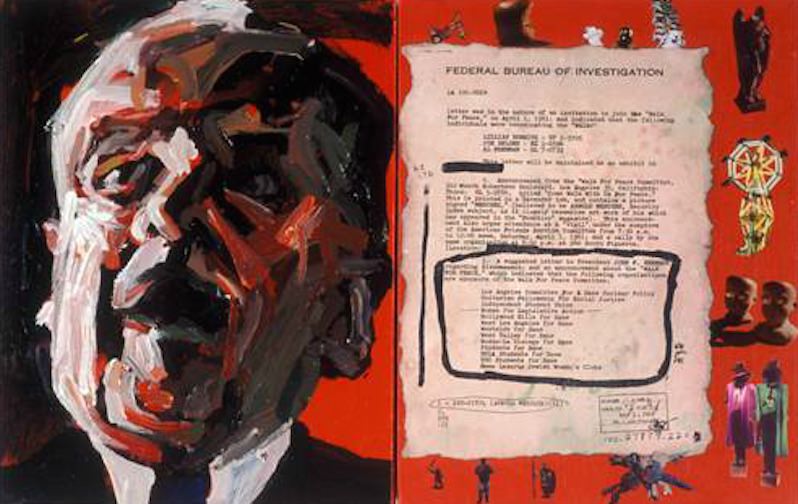

“The F.B.I. Files 56” by Arnold Mesches. (arnoldmesches.com)

The death of renowned artist Arnold Mesches at 93 on Nov. 5 almost closes a chapter on one of the greatest generations of socially conscious artists in American art history. Throughout Mesches’ long and distinguished career, he used his talent to provide incisive visual commentary about the major social and political issues of his time.

READ, WATCH, LISTEN: A Revolutionary Art Form That Leads to Social Change

His deceased contemporaries, among the giant political artists born in the early 20th century, included Milton Rogovin (1909-2011), Jack Levine (1915-2010), Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) and Leon Golub (1922-2004) and his wife, Nancy Spero (1926-2009). Only May Stevens, born in 1924, survives among the iconic political artists from that time.

For 70 years, Mesches’ work spanned a wide variety of social and political themes, including war, economic injustice, social class inequalities, racism and political persecution. Mesches was influenced by giant figures of European social art, including Pieter Bruegel, Francisco Goya and Käthe Kollwitz; American social realist Ben Shahn; and the Mexican muralists José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera.

Although not as publicly visible as some of his peers, Mesches was widely recognized and respected by generations of American visual artists, especially those women and men who combined exemplary technical expertise and talent with a trenchant vision of the defects of American social, political and economic life. And like many socially oriented artists of his generation, he was politically active, taking his views to the streets as well as to his canvases.

His vision led to the same harassment and persecution that thousands of other progressives encountered during the anti-communist hysteria of the post-World War II era. As Mesches recounted, agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation followed him because of his leftist views and actions. They took photos, tapped his phones, accepted reports from informers and closely monitored his personal and professional activities. Agents also questioned neighbors, students, fellow artists and supposed friends about his left-wing views and actions.

This was commonplace during the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s during the repressive era of Sen. Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin and the tyrannical and paranoid regime of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. Some of America’s finest artists and entertainers suffered egregious (even fatal) harm during this dark period. It would be foolish to assume that that era is a mere historical relic, never to be repeated in a more enlightened America.

On Aug. 6, 1956, Mesches’ art studio was broken into. The intruders appeared to have information that guided them to his drawings and paintings that addressed the case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Two hundred artworks, as well as art supplies and other objects, were stolen, an especially horrific injustice against an artist.

It is worth noting in this memorial tribute to Arnold Mesches that any artist who supported the Rosenbergs was especially daring. Few Americans in any field publicly condemned the U.S. government for its trial and execution of the two alleged Soviet atomic spies. Still, international artistic luminaries—including Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Karel Appel, Renato Guttuso, Francisco Mora, Louis Mittelberg and others—helped galvanize world attention and condemnation of the witch hunt underway in the U.S.

A small number of Mesches’ American artistic contemporaries—including Fred Ellis, Hugo Gellert, Rockwell Kent, Victor Arnautoff, Rudolf Baranik, Leon Marcus and Alice Neel—also addressed the Rosenberg case and the deeper political repression of the times. Many of these artists had associations with the Communist Party and were likewise targeted for blacklisting or other persecution. But their works nevertheless stood as visual beacons of resistance during a period of suffocating political and cultural conformity.

In the 1950s individual and institutional silence restricted political dissent, and the orthodoxy of abstract expressionism discouraged visual social commentary and even figurative art generally. That visual movement, which highlighted abstract painting in various forms, became the major American art form of the times. It relegated political art to the margins of critical commentary and made political artists largely irrelevant in scholarly and journalistic criticism for many years.

In 1989-90, curator Rob Okun organized an extensive exhibition of Rosenberg-era artworks that traveled throughout the United States, including the Otis Art Gallery in Los Angeles, where Mesches lived and worked for much of his life. “Unknown Secrets: Art and the Rosenberg Era” contained works by Mesches as well as by most of the foreign and American artists noted above. The show also highlighted artworks created specifically for the exhibition by major contemporary figures.

Although this remarkable exhibition occurred more than a quarter century ago, the efforts of Mesches and others have stunning contemporary relevance. Subsequent evidence reveals that Julius Rosenberg was guilty of espionage-related criminal conduct. Many legal observers conclude, however, that the death penalty for him was excessive, a reflection of the anti-communist hysteria of that era. The greater injustice occurred with the execution of his wife, Ethel, a probable innocent victim of that same hysteria. At present, a campaign to “Exonerate Ethel” is underway. Although the chances for success are low, the quest reflects the same moral fervor that animated Mesches and his artistic colleagues in the never-ending struggle against injustice and oppression.

In 1999, Mesches invoked the Freedom of Information Act to get access to his FBI files, a natural response to the years of harassment he suffered. He received 760 pages of information about his activities and his personal life between 1945 and 1972, but nothing about the break-in at his studio. Much of the information was trivial: his children’s birthdates, the makes of his cars, the names of casual friends and acquaintances, and the like. Such information is typical, suggesting that FBI agents not only violated citizens’ privacy rights but also wasted substantial amounts of government money in useless and trivial pursuits.

The files had large portions blacked out, probably the names of informers, some of whom most likely had close personal contact with the artist: models who posed for him, students in his classes, neighbors and others, in a time eerily reminiscent of the Stasi in the former German Democratic Republic. What struck Mesches, beyond the sheer horror and lunacy of these FBI files, was their perverse aesthetic quality. He compared the large black slashes in the files with those in Franz Kline’s abstract expressionist paintings and sketches, and determined to transform these documents into durable works of socially conscious art.

The result was his most well-known artistic series, “The F.B.I. Files.” Mesches cut and pasted 57 documents from his FBI files in a magnificent collection of more than 50 works. This nationally and internationally acclaimed exhibition traveled throughout the United States from 2002 to 2004, including to the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. For the art itself, Mesches combined actual pages from his files with news clippings, personal photographs, 1950s-era commercial imagery and handwritten text.

These works are highly colorful collages that combined high visual appeal with chilling historical content. His popular cultural imagery juxtaposed cigarette ads, movie stars, robots and Batman with civil rights demonstrations, images of Malcolm X, Marilyn Monroe, Richard Nixon, Nikita Khrushchev and others. This pastiche provides a remarkable glimpse into a troubled time of recent American history. Above all, the works reveal, in dramatic visual language, the frightening political climate of the era—a vision rarely taught in the nation’s schools or communicated in the dominant institutions of mass communication.

I saw that educational deficiency firsthand when I took some my university students from UCLA to visit the “F.B.I. Files” exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center in 2004. Although all the students had heard of McCarthyism in vague and general terms, none had any specific idea of the pervasive evil of FBI surveillance. Mesches’ artworks, with their appropriation of his actual files, provided them with a concrete vision of the wholesale abrogation of constitutional rights in the postwar era. This was a stunning educational breakthrough to most of them and a further reminder of art’s extraordinary power as a historical corrective.

Arnold Mesches lived a long, creative, and deeply admirable life. His legacy is especially compelling for younger artists in every medium. These artists must challenge the repressive forces of corporate and governmental powers whenever they appear. In the new Donald Trump era of potential abuses of civil liberties, rollbacks of civil rights, environmental degradation, military adventurism, and neglect of women, people of color, sexual minorities and others, the need for socially engaged art is more urgent than ever.

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.