Death’s New Context

In this excerpt from the foreword to "Stranger to History," Aatish Taseer reflects on the political assassination of his father in Pakistan last year and how the message of his book, published in the U.K. in 2009 and recently in the U.S., is even more relevant today.

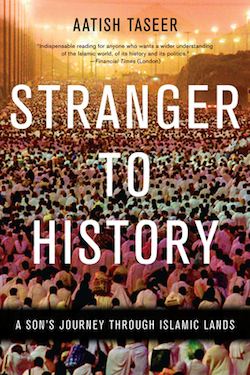

Excerpted from “Stranger to History: A Son’s Journey Through Islamic Lands” by Aatish Taseer. To read Truthdig’s review of the book click here.

In the last days of his life, my father, whose love of Pakistan prevented him from seeing it clearly, found himself declared its enemy. His crime was his defense of another enemy: Aasia Bibi, a Christian woman accused of blasphemy after drinking at her village well (there is a distinct suggestion of caste to this story: of the old Hindu caste system and Untouchability — though strictly forbidden in Islam — still hanging on in Pakistan after all these years). Because his country was founded in faith and blood — a million people had died so that it could be made — my father could not say that the grounds on which she was condemned were wrong; the grounds stood; what he sought for Aasia Bibi was clemency. But it was enough to demand his head.

What he never could have said is what I suspect he really felt: ‘The very idea of blasphemy law is primitive; no woman, in any humane society, should die for what she says and thinks.’ And when he sought the repeal of the laws by which she had been condemned, the laws that had become an instrument of oppression in the hands of a majority against its minority, my father could not say that the source of the laws, the faith, had no place in a modern society. He had to find a way to make people believe that the faith had been distorted.

But the clerics and the media, the same men who in another time had condemned Manto, didn’t believe my father; they could tell that he was part of a godless and westernized elite. And one of the only times in my life that I have seen my father scared was during a TV interview with a Pakistani journalist, a woman with a painted face and blow-dried hair, who would not accept his rationale for opposing the blasphemy laws. At last, exasperated, he said: ‘Why do you keep making it seem as if I, myself, am guilty of blasphemy? I’m not, I am absolutely not. …’

In those last few weeks, when they were burning him in effigy and declaring him fit to die at nocturnal rallies, at which his bodyguard assassin was present, he seemed to sense the trouble he was is. In one TV interview, available now on YouTube, a journalist sympathetic to his cause asks if he is nervous about having excited the passions of the religious men. My father replies that many people had told him to steer clear of the issue, many had warned him of its dangers; but he had felt, he says, quoting his uncle, the poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz: ‘Let’s go today in fetters through the bazaar, with our wounded hearts bound fast, to our death we go, come, friends, let us go.’

My father, whose father had also been a poet, and who grew up surrounded by Urdu poetry, had much occasion at the end of his life to quote from the poets. These snatches of verse, to be found now in a YouTube video, now in some final tweet, form a macabre compendium, unbearably painful, of a man seeming to anticipate his death. There is the famous verse from the Punjabi poet Munir Niazi, quoted in an interview: ‘In part, the road was hard, in part, I wore a collar of grief about my neck. In part, the people of the town were cruel, and yes, in part, I, too, knew a taste for death’; there was the Faiz; and, literally days before he died, there was Shakeel Badayuni: ‘So robust is this body that it knows no fear from stray fires, it fears only the fire of the flower [within], that alone can set the garden ablaze.’

A few days later, on a dismal January afternoon in Islamabad, as he left a restaurant where he had been having lunch with a friend, his twenty-six-year old bodyguard, persuaded of my father’s designation as an enemy of the faith, shot him to death in the street, firing round upon round in the presence of the rest of the guards who did nothing to stop him. Within hours, the components of Pakistan’s parallel morality, a morality distorted by faith, fell into place.

My father’s killer was showered with rose petals, billboards of him were erected through the city of Lahore, men came to give food and money in thanks for what he had done, and there were vast rallies of support demanding he be freed. The senate, which in the months to come would have a prayer to say for Osama bin Laden, was unwilling to pass a simple motion to condemn the killing. Those who defended my father, in no matter how small a way, were themselves either killed or forced to leave. In March, Shahbaz Bhatti, the minister for minority affairs, who had joined my father in opposing the blasphemy laws, was gunned down by unknown men outside his house in Islamabad; in August, the cleric who had performed my father’s funeral rites when no one else was willing was forced to flee the country; and, in October, the judge who dared hand down a death sentence against my father’s killer left for Saudi Arabia, after his court was smashed up by protestors.Pakistani liberals — who themselves constitute the tiniest of tiny minorities — like to say that these are the actions of a still tinier minority: the extremists. Perhaps they are right; I, for one, don’t believe that they could occur without the quiet assent of the majority. And, in any case, what cannot be denied is that my father, who loved his country, died wretchedly in Pakistan, forgotten and un-mourned by the majority, an enemy of the faith. It was a death that recalls the last sentence of Franz Kafka’s The Trial: ‘“Like a dog!” he said. It was as if he meant the shame of it to outlive him.’

Some days after his death, I had written:

Though I believe, as deeply as I have ever believed anything, that my father joins that sad procession of martyrs — every day a thinner line — standing between him and his country’s descent into fear and nihilism, I also know that unless Pakistan finds a way to turn its back on Islam in the public sphere, the memory of the late governor of Punjab will fade.

And where one day there might have been a street named after him, there will be one named after Malik Mumtaz Qadri, my father’s boy-assassin.

A year to the day, that forecast, grim as it sounds, still stands; so, too, does this book, Stranger to History. It is a source of some satisfaction to me that my account of the countries I visited on that eight-month journey from Istanbul to Lahore is more relevant today than when it was written. In Turkey, I believe it is possible to see in the story of a man like Abdullah the new equilibrium that would be reached in the Erdogan years between Islam and Kemalist secularism. In Syria, one cannot but have an intimation of the disturbance that lay beneath the apparent placidity of the Assad regime and that would come boldly to the surface five years later during the Arab Spring. In Iran, through women like Nargis and Desiré, we meet the kind of people who became the face of the now suppressed Green Revolution.

But nowhere is the book more relevant — and here is a little irony — than in Pakistan, where it anticipates so much of the violence and futility that was on the horizon. But, here alone, there is little pleasure for me, and a considerable sadness. For writing Stranger to History came at the price of losing my relationship with my father; and, in the end, I was, as I had been for so much of my life, estranged from him.

I cannot say I regret writing it; I don’t. This book made me who I am; it was my reclamation of the past. If there is regret, it comes only from having had the fortune to see, more clearly than my father could ever have allowed himself to, the place his country had become.

January 2012

New Delhi

©2012 by Aatish Taseer from “Stranger to History.” Reprinted by permission of Graywolf Press.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.