Seven Movies I Liked in 2012 (and One I Didn’t)

The film year is, alas, a "disappointment." The very idea of making a 10 Best list seems either laughable or a task comparable in difficulty to translating the Rosetta Stone.

I’ve been reviewing movies since 1965 and on the final day of the year, the time for the great annual summing up, the message is always the same. Or so it seems. The film year is, alas, a “disappointment.” I suppose, sometime over the course of nearly half a century — I really must get a life! — there was a year or even two that was, in retrospect, at least passable.

But mostly it appears to me that I could simply take last year’s piece, change the names of the handful of movies I really liked, and simply repost it. No one would ever know, since its immortality depends entirely on my laziness in clearing out the “Articles — Recent” file on my computer, which probably should be retitled “Articles — Ancient.” Or “Irrelevant.”

But the truth of the matter is that I am ever the optimist. I don’t think you can be a movie reviewer — however dour the poses honesty requires you to strike — without having that component to your character, without feeling a sense of regret when stern duty compels you to speak up, as people start nominating negligible films for awards, and the very idea of making a 10 Best list seems either laughable or a task comparable in difficulty to translating the Rosetta Stone. Four or five is the best I can ever manage — after which I require a long nap and maybe a shot or two of strong drink.

But to wit: “Amour” was, I strongly felt, the best movie of the year. As you doubtless know, Michael Haneke’s picture is small and simple: A woman (Emmanuelle Riva) suffers a stroke and her husband (Jean-Louis Trintignant) must nurse her through her final illness. They are patient and humane with each other until, finally, that is no longer possible. The acting by this pair is impeccable and an ending is achieved that is, in some sense, uplifting. Movies, of course, are full of melodramatic death — it is in some sense their only subject — but it is rare for them to contemplate it with the calmness, the fatedness, the reality that “Amour” does. This is how, more or less, it will come out if we are spared to great age — and we are vastly the better for the clarity with which this limpid and lovely film invites us to think about the inevitable.

Nothing seems quite in the same league as “Amour.” But there are a few films that as the months wear on, and a lot of promising stuff somehow doesn’t seem to pan out, begin to look better than one originally thought. Like “Argo.” I said at the time that in years past, Hollywood used to turn out a number of such agreeable and entertaining films every year and that we tended to receive them as business as usual, something we were entitled to as a reward for all our good faith moviegoing. I think that remains the case — except the combination of easy professionalism, good wit and suspenseful construction that’s on display in this movie is much rarer now than it was in former times. As the year ends, Ben Affleck’s movie is earning slightly inflated praise for its smoothness and good nature. I find I’m OK with that. Implicit in this approval is a wish for more of the same from Hollywood. Can it really be that it has lost its knack for smart, insinuating fun? Considering the number of films that try and fail in “Argo’s” once-fecund field, I think that is sadly the case. C’mon guys! Try harder. Are you really dumber and more fumble-fingered than the filmmakers of the ’30s and ’40s? Don’t answer that. You’ve got “Silver Linings Playbook” to answer for. And a lot of similar flapdoodle besides.

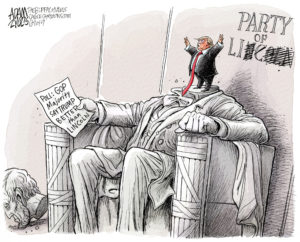

This does not include “Lincoln.” I was, of course, respectful of it when it came out. How could you not be? Yards of good-to-great acting, led by Daniel Day-Lewis and Sally Field, a serious and literate script that pays due regard to Lincoln’s gift for telling tales and anecdotes, but under Steven Spielberg’s direction, never sells out the issues he was grappling with in the last months of his presidency. Since the film’s November release, Lincoln scholars have not, as I read them, made any charges that stick against the movie’s historical veracity and the comparisons I’ve seen to the several well-meaning and serious Lincoln films of the past are all in the current film’s favor. In short, it has, in a very brief time, grown in stature.

“Lincoln” stubbornly remains a chamber piece, and this resistance to the epic gesture is very much to its credit. The fact that it has grossed well over $100 million (with more to come in the onrushing awards season) perhaps says something heartening about the American audience’s willingness to get serious one or two times a year — especially when the Spielberg name is attached to it.

But that somehow reckons without Tommy Lee Jones. Let’s face it, good as the movie makes us feel for allowing to indulge the serious angels of our natures, it needs a jolt. Good of Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner to recognize that fact — and to allow Jones the full range of his deliciously over-the-top performance as Thaddeus Stevens, the rootin’-tootin’ abolitionist who sort of steals the show in about a half dozen hilarious, yet somehow deadly serious, scenes. I can imagine Spielberg gulping guiltily when he saw what the actor was getting up to (or not, I have no way of knowing), disturbing the peaceful tenor of this austere film. But more power to all concerned for conspiring to save it for — yes — humanity’s vulgar side. It is what it needs to rescue it from gentility, from taking itself too seriously. There are many aspects of “Lincoln” that commend it to our attention, but we must not forget what this bold and fulsome performance contributes to it.

That’s not quite it for 2012. I think I’m virtually alone in believing “Hyde Park on Hudson” is a witty representation of the complexities of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s romantic life on the eve of World War II, and with the relatively new king and queen of England visiting him at his home and worrying, among other things, about whether they dare to eat a hot dog at a picnic the president has laid out for them. Bill Murray is both insouciant and sober as FDR and this is a very likable movie — more so than a lot of pictures that try harder for that illusive quality.

No year-end rumination would be complete without mention of a good movie that no one paid the least attention to in the year just past. My nominee in that category is “Monsieur Lazhar,” writer-director Philippe Falardeau’s thoughtful study of a schoolteacher in Canada who is hastily recruited as a substitute for an instructor whose suicide has traumatized a school. Played by Mohamed Fellag, he is an exile from Algeria whose family has been murdered and who is applying for residency in Canada. If he does not receive it he will be sent home — to almost certain death. He is a humane and decent man, an imaginative pedagogue, and the way his fate works out is complicated and ultimately satisfying. Films like this don’t really have a chance in today’s Hollywood — minor, character-driven movies don’t usually do — but it is impeccably crafted and heartfelt without being the least bit sentimental. It is worth seeking out.

So too are several of the year’s documentaries. I’ll mention just two of them, starting with “Mea Maxima Culpa,” subtitled “Silence in the House of God.” It is an extremely powerful study of child abuse among the Catholic clergy. The film begins and ends with a case in Wisconsin, but it ultimately, infuriatingly encompasses what seems to be the entire Catholic hierarchy. Its voice is calm, but its passion is huge and devastating. And terribly persuasive. Then there is “The Invisible War,” director Kirby Dick’s study of what he calls the “epidemic” of rape in the American military. It is perhaps a little overlong, but you cannot deny that a situation in which rank (among other factors) can compel women (and some men) to unwanted sexual encounters has the potential for brutal consequences. Neither of these films is sensational, but they are compelling. And they both represent, it seems to me, a welcome broadening of topics that are acceptable for the documentary impulse.

And now, at last, we have arrived at that inevitable, regrettable topic — the year’s worst movie. We are not, of course, talking about slasher pix and all the other junk that moves beneath our lofty gaze. I like to confine my choice in this category to films that are intended for the mainstream, for audiences that are looking for nothing more than a nice, reasonably intelligent time at the movies — nothing special, but something that passes the time agreeably and certainly does not waste it. I’m going to choose, from the usual vast list of candidates, Judd Apatow’s “This Is 40.” This is a movie that deals with the problems common to a family reaching that watershed date — money is short, sex has lost its zing, the kids are fractious. These problems are sometimes discussed while someone is sitting on the toilet. Or is in the midst of a visit to the doctor for a breast examination. This is supposed to add “realism” to the proceedings, which are said to be somewhat autobiographical. I wouldn’t know about that. And I surely wouldn’t know what critics I respect see in the movie. I do know that it is disastrously unfunny, as it lurches from one clichéd situation to another, from, typically, Viagra jokes to not-very-lustful glances up the skirt of a young woman perched on a stepladder. Apatow can be an agreeable filmmaker, but here he’s a lazy one and the success of the movie occasions dim thoughts about the feckless tastes of his equally lazy audience members, so used to being gulled into submission to ineptitude that they begin forgetting the damned thing before they escape the lobby.

It’s the weary duty of carping critics to remind everyone that funny is as funny does. And, I suppose, to wish everyone better luck next year. Not that I have any confidence in that scenario — except, naturally, for the blessed handful of exceptions that prove the rules.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.