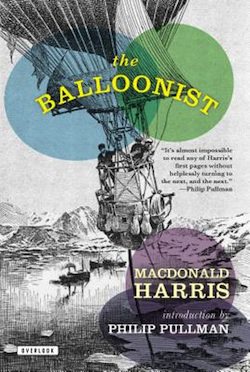

The Balloonist

MacDonald Harris is a writer "too good to be neglected," writes Philip Pullman in the introduction to this reissue of Harris' highly original 1976 novel "The Balloonist." Set in 1897, it follows a middle-aged Swedish aeronaut as he aims to sail over the Arctic in a balloon to the North Pole.Set in 1897, "The Balloonist" follows a middle-aged Swedish aeronaut as he aims to sail over the Arctic in a balloon to the North Pole.

“The Balloonist” A book by MacDonald Harris

When MacDonald Harris’ “The Balloonist” first appeared in 1976, it was acclaimed by Mary Renault as a “tour de force,” while other reviewers emphasized its “ruminative elegance” and its assured interweaving of “the scientific, the sensual, and the philosophic.” Described by one critic as blending the romance of Jules Verne’s “Voyages Extraordinaires” with John Fowles’ “The French Lieutenant’s Woman,” the novel was rightly nominated for a National Book Award.

For this new Overlook edition, Philip Pullman — who created his own memorable 19th-century-style aeronaut in “The Golden Compass” — contributes an exceptionally thoughtful appreciation of “The Balloonist” and its author’s overall artistry. Each of Harris’ 16 novels, Pullman declares, is not just remarkably “interesting” and “gripping” but is also composed in “a superbly flexible, elegant and witty prose.”

Under his real name, Donald Heiney, Harris (1921-1993) taught writing at the University of California at Irvine, where one of his students was Michael Chabon. As an editor for Book World during the 1980s, I assigned several of Harris’ novels for review — including such major works as “Tenth” and “Herma” — and nearly all of them received rapturous notices. As Pullman says at the end of his introduction to “The Balloonist,” Harris is simply a writer “too good to be neglected.”

So how come you haven’t heard of him? How is it that his books — often loosely fantastic or magic-realist — are out of print? You tell me. One can only hope that Overlook will reissue more of Harris’ highly original work.

“The Balloonist,” set in July 1897, is narrated in the present tense, with abundant flashbacks, by a middle-aged Swedish aeronaut named Major Gustav Crispin. In a three-person balloon, the major, along with an omnicompetent American newspaperman named Waldemer and the youthful, quiet Theodor, aims to sail over the Arctic reaches to the North Pole.

From the start, most people believe that the expedition is doomed to failure. No matter. “I am going forth of my own volition to join the ghosts of Bering and poor Franklin, of frozen De Long and his men. What I am on the brink of knowing, I now see, is not an ephemeral mathematical spot but myself.”

Clearly a philosopher as well as an explorer and a scientist, the major believes that “the outward events of our lives bear little or no relation to what is really happening to us”: The present as much as the past can sometimes seem just a magic lantern show. Given the blurring of what is real and what is remembered, “The Balloonist,” despite its boys’-adventure trappings, quickly becomes a journey into the interior of the self. In this book, to quote an uncannily appropriate line from Wallace Stevens, “Crispin / Became an introspective voyager.”

As “The Prinzess” soars northward, encountering storms of ice and snow, the major recreates, in vivid detail, the history of the erotic tango of his love affair with an enigmatic 19-year-old named Luisa. Coming from a wealthy, cosmopolitan family in Paris, Luisa is ardently modern, straining against the barriers of what is proper and improper for a well-brought-up young lady.

When the major impulsively invites her on a short balloon ride in Finland, she immediately accepts. After they crash-land, the two find shelter in a peasant’s hut. While outside a winter storm rages, inside, before the fire, a towel slips, a hand accidentally touches a breast, and the pair sinks, convulsively, into a feather bed.

The major’s memories, even of the most erotic moments, are related in a slightly formal tone, though his descriptions can be as sensuous as Nabokov’s. Shortly after the Finnish interlude, Theodor, a student at a military school, unexpectedly appears at the balloonist’s Paris apartment. Are Crispin’s intentions toward his sister Luisa honorable? In truth, the major doesn’t seem to know what they are.

As for Luisa, she is so volatile and changeable that one can never be sure what she will do next. Most of the time she behaves with decorous modesty and is resistant to any repetition of the Finland episode. But at other times, as at her family’s Italian villa in Stresa, in the yellow bedroom. … What’s more, she clearly has her own secrets.

As the major recalls these scenes of his life, the balloon gradually makes its way into a heart of whiteness. The practical Waldemer keeps busy taking photographs, Crispin consults a kind of primitive radio that picks up the crackle of oncoming storms, and Theodor eagerly takes on the most daring tasks, such as climbing up ropes to knock off the ice forming on the balloon. There are detailed technical descriptions of everything, starting with how to brew coffee when the slightest spark could set off an explosion.

Meanwhile, during rest periods, the major recalls more and more of his life with Luisa, especially their quarrels over love and work, and over sexual and social roles. In fin de siecle Paris, the hidebound traditions of the 19th century are gradually being swept away. The major remembers the night he and Luisa attended a raucous performance of Alfred Jarry’s parodic black comedy “Ubu Roi.” Meanwhile, their intimate life grows increasingly complex and kinky. Luisa sees the world as “a hell of circles, and each one of us is trapped in a different one. Millions of circles, millions of damned souls.” She hates living in her “Quai d’Orleans” world while the major yearns for his “wires and sparks.” This beautiful young woman desperately wants to escape from what the world constrains her to be. And eventually she does.

Similarly, the major absolutely must fulfill his own destiny, and that means adventure at the ends of the Earth. At one point, the three aeronauts, having landed their balloon, are suddenly attacked by killer whales, which, mistaking them for seals, ram the ice and try to knock the explorers into the freezing water. Like all the polar scenes of “The Balloonist,” these pages are vividly realistic.

Thematically, however, the novel always returns to the question of identity, of how each of us is frozen, trapped in the ice of social and sexual conventions. As Luisa tells the major: “What I wanted — what we wanted — was to make a world that we could both inhabit. That would be both yours and mine.”

While the comparison to Verne is inevitable in any novel called “The Balloonist,” there is a hard, crystalline quality, reminiscent of Rilke’s poetry, to Harris’ bleakly exhilarating vision. Little wonder that the major reformulates the famous opening line of Rilke’s first “Duino Elegy” into a declaration about the empty frozen north: “No one among the angelic orders will hear us if we cry out.”

Every so often, one discovers a novel that simply stays with you, that haunts your imagination for days after it’s closed and put back on the shelf. “The Balloonist” is that kind of book. It is also perfect reading for winter.

Michael Dirda reviews books weekly for The Washington Post.

©2013, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.