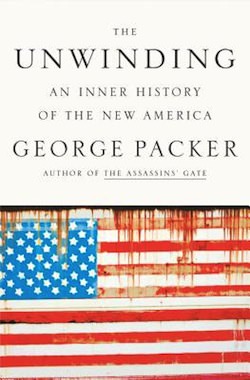

The Unwinding

This book's vision of how things went bad over the past generation covers such diverse topics as the fast food-obesity nexus, the loss of localism, the end of cheap oil, the housing collapse and, above all, the death of trust.Author George Packer's vision of how things went bad over the past generation covers such diverse topics as the end of cheap oil, the housing collapse and, above all, the death of trust.

“The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America” A book by George Packer

In Youngstown, Ohio, in 1977, the mills close and 5,000 people lose their jobs, and then the shops shutter and the houses burn and people leave in droves. In North Carolina a decade later, Wal-Mart, crack and meth displace local commerce and community. In Washington, D.C., an idealistic public servant arrives expecting to work for the people back home but discovers that big money has taken hold of the city, incentivizing civil servants to cash in and toil for the very entities that they had come to town to fight.

In the everydays of a handful of Americans — including a former autoworker turned community organizer in woefully declining Youngstown, a dreamy entrepreneur in rural North Carolina and a pol in Washington — there is a window on the big picture of a disillusioned and dispirited nation, torn from its hopes and expectations. This is “The Unwinding,” the story of our time, the relentless empowerment of the wealthy and the silencing of the great American engines of mobility.

George Packer, a longtime and highly versatile reporter for The New Yorker, travels to the America that politicians and other leaders prefer not to see. In “The Unwinding” Packer leaves the anomalies of Washington and New York behind and shows how Wall Street, big corporations and the government atomized and polarized us, unspooling “the coil that held Americans together.” In this America, he writes, “everything changes and nothing lasts.” The reporter’s vision of how things went bad over the past generation covers everything from the fast food-obesity nexus to the loss of localism, the end of cheap oil, the housing collapse and, above all, the death of trust.

Packer’s is a big book, using close portraiture to make huge conclusions about who we’ve become and what we’ve lost. That is the glory of this book, and that is its flaw as well.

When Americans dreamed big, they wrote big, too. From Whitman to Dos Passos, from Mailer and Updike to Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson, novelists and journalists found in the lives of ordinary Americans a hardy, wily individualism and rock-ribbed belief in opportunity, a path out of dark times. But in this era of diminished resources, extreme inequalities and fraying institutions, the chroniclers of our times suffer from pinched ambition, too. In books, magazines and newspapers, shrunken budgets press writers to devote much of their energy to narrowcasting that tells people what they want to hear.

So it’s a thrill to see a reporter dig deep into the lives of people who have been ravaged by greed, a people who naively kept believing in mobility even as the elites changed the rules. Packer’s character in Youngstown, Tammy Thomas, watches her children move across the country in search of work, and although she resents that the country has changed in ways that splintered her family like that, she understands that they had to go. In her town, every major institution failed: industry, banks, unions, churches, schools, government.

Packer is at his best when he follows his characters into their daily struggles, when he travels with Dean Price in North Carolina as he tries to come back from bankruptcy by peddling his new scheme to convert restaurants’ waste cooking oil into biodiesel for local schools’ bus fleets, or when Jeff Connaughton, the D.C. public servant, discovers that the civics-class version of how a bill becomes a law has morphed into a rigged game in which all the major players are in the monied establishment’s camp.

|

To see long excerpts from “The Unwinding” at Google Books, click here. |

The stories of the three main characters are interrupted by staccato headlines from the past two decades; an extended and richly revealing portrait of life in Tampa, epicenter of the foreclosure fiasco; and odd little canned sketches of famous Americans — Newt Gingrich, Sam Walton, Robert Rubin, Jay-Z — who thrived in elite bubbles that feel like an alternate universe compared to the collapse of the rest of the country.

That juxtaposition would have been enough to dramatize the divisions that now define the nation, but Packer is less effective when he slips into angry, sometimes snide generalizations: Tampa “was a torpid apocalypse,” Americans “no longer believed in the future,” and “the real America” is a place of “fallow farms and disability checks and crack.” He’s far better when he lets his reporting work its magic, when he shows how the Obama administration let its focus on the health care bill suck up all the air in Washington after the crash of 2008, leaving his supporters to wonder what had happened to the guy who was going to be their advocate for jobs; or when he connects the dots between the hedge fund manager who makes a $400-million profit on a company in which he invested $14 million even as that company lays off thousands of workers and then rehires a few of them to do double the work at half the pay.

In the end, Packer’s dark rendering of the state of the nation feels pained but true. He offers no false hopes, no Hollywood endings, but he finds power in another strain of American creativity, in the stories of Raymond Carver and the paintings of Edward Hopper, in the dignity and heart of a people who grow deeply lonely as their lives break down, but who somehow retain muscle memory of how to climb back up.

Marc Fisher is a senior editor at The Washington Post. His email address is [email protected].

©2013, Washington Post Book World Service/Washington Post Writers Group

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.