The Performance of Robert Redford’s Career

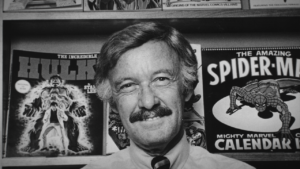

The 77-year-old actor is at his smart, ironic best in "All Is Lost."

There is a fascinating resonance between the film “All Is Lost” and the manner of its making. The very good Robert Redford movie about a shipwreck and a fellow known only as “Our Man,” desperate to keep his smart little boat afloat, has only one character, who hardly speaks at all (nobody to talk to and, anyway, he’s always fighting the ever-inclement elements, not to mention the temptation to despair). It’s very simple: It gives new meaning to the term “minimalist” — and, perhaps, to the label “action movie.”

“All Is Lost” is the latter, but on the smallest imaginable scale. That is to say, Our Man’s only possible hope to save his ship (and himself) is pretty much nonstop patching and bailing and riding out a plethora of storms. It gives away nothing to say that the ship and its comforts are lost fairly early and that Our Man spends most of the voyage in an uncomfortable dinghy, trying to teach himself how to use a sextant that, thank God, turns up, in order to find his way to the major shipping lanes of the Indian Ocean, where he has perhaps a prayer of being spotted and rescued. It helps, naturally, that Our Man is an up-and-doing sort of guy and a resourceful one. He also has a razor, which helps keep his morale up, scheming to fight on, yet also fighting the despair that unavoidably creeps in on him. Neatness counts — everything counts in this movie. The thing is, you may not know what’s important, until it’s too late.

It is probably the performance of Redford’s career. He has always been a smart and ironic underplayer, but this is a bold choice to make for an actor in his late 70s, when the temptation to cruise along accustomed courses must be heavy and well earned. I’m around that age myself and I must say I would have given up this struggle long since. But, of course, that’s why they make movies, isn’t it? To restore our hopes for the improbable.

And being tough minded, as Redford is, helps a lot. He’s not invulnerable — he has the grace to show fear in carefully doled out amounts. And, better still, the grace to keep his secrets. We never know why he has chosen this test. About all we know about him is that he’s married (wedding ring) and capable, within reason. You can speculate that this is some kind of late midlife test for him, though I’m inclined to let him just be a knothead if that’s what he wants to be. He’s well served by writer-director J.C. Chandor’s work. It’s not super-heroic. Our Man has a mounting set of problems and he does his best to solve them. The film’s style is austere and the director’s choices are elegant without being showy.

The outcome of “All Is Lost” remains in doubt — right up to its final moment (Chandor saves the onset of despair to the end, which is a wise and powerful choice). We know that this movie is about the will to survive and we want to know if that’s enough. I’m not telling. And you shouldn’t either. For once those people who insist on keeping a movie’s secrets are right. You should just shut up. And see the movie. You are unlikely to see a better, wetter story of the will to survive than this one. This is one of those rare films that tests the limits of what a movie can — and cannot — be. And in its modesty of means and unpretentious skills, it turns out to be rather more than you might have thought likely.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.