Two Weeks Full of Domestic Dissatisfaction

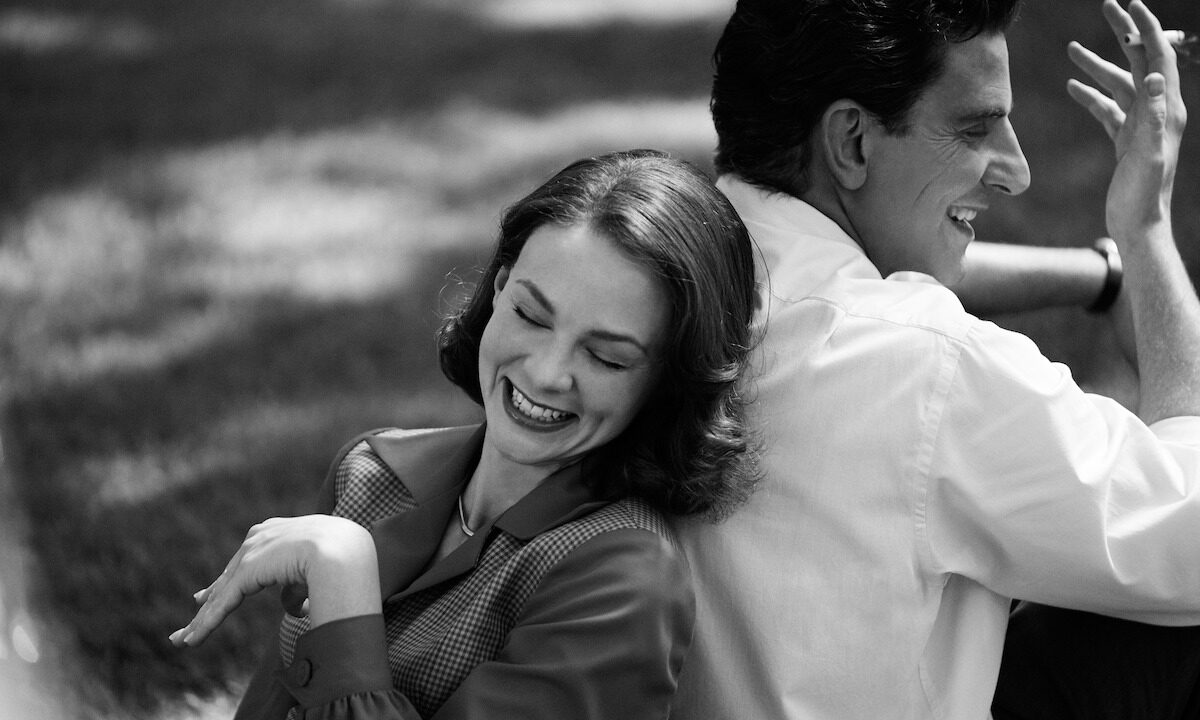

At the 61st New York Film Festival, the marquee debuts interrogated partnerships and marriage. Scene from the movie “Maestro,” co-written, co-starring, and directed by Bradley Cooper, about the flamboyant conductor Leonard Bernstein, who was queer, and his marriage to Alicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan), who was straight. (Photo: Courtesy of Netflix)

Scene from the movie “Maestro,” co-written, co-starring, and directed by Bradley Cooper, about the flamboyant conductor Leonard Bernstein, who was queer, and his marriage to Alicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan), who was straight. (Photo: Courtesy of Netflix)

The modern film festival was born as politics by other means. In 1932, the first international cinema conclave was established by Benito Mussolini’s finance director, Giuseppi Volpi, in Venice. When it soon became clear that the annual event was nothing but a propaganda arm of the Italian Fascists, cultural authorities in Paris began planning a riposte on the French Riviera. The timing, however, was poor. Scheduled to debut in September 1939, the French event was canceled following Hitler’s invasion of Poland on the first of the month. The inaugural Cannes Film Festival would not take place until 1946.

The origins of the New York Film Festival are found in the lower-stakes cultural politics of mid-20th century America. The mission of founders Richard Roud and Amos Vogel was to introduce American audiences to the experimental and politically engaged films being produced in other parts of the world, and expand their horizons beyond the formulaic products of Hollywood. The first New York Film Festival, held in 1962, featured a bounty of what became known as “international art cinema,” including Luis Bunuel’s “The Exterminating Angel,” Yasujiro Ozu’s “An Autumn Afternoon” and Chris Marker’s “Le Joli Mai.”

The 61st New York Film Festival, held during the first two weeks of October, did not contain an agenda as overt as the first. Still, a selection of contemporary movies from around the world still has the power to locate and reveal a zeitgeist. Consider Yorgos Lanthimos’ mischievous “Poor Things,” a grotesquely funny hybrid of “Frankenstein” and “Candide,” shot through a fisheye lens. Willem Dafoe stars as a Victorian doctor whose unusual daughter, Bella, delights in sexual adventure and discovery. Like so many characters in the festival’s program this year, she is puzzled by the gender inequities she discovers within domestic partnerships and marriage.

Because drama is based on conflict, marriage has always held a strong appeal as a cinematic motif and plot device.

The festival’s 61st program contains portraits of three similarly challenging marriages: “Maestro,” co-written, co-starring, and directed by Bradley Cooper, about the flamboyant conductor Leonard Bernstein, who was queer, and his marriage to Alicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan), who was straight; “Priscilla,” written and directed by Sofia Coppola, about the burdens of being married to Elvis Presley (Jacob Elordi); and “Ferrari,” directed by Michael Mann and starring Adam Driver in the title role and Penelope Cruz as his wife, Laura.

It took a day or so to process that “Maestro” and “Ferrari” are not strictly biopics about great men and their achievements. (Though they did conform generally to tropes about the burdens of male genius, while serving as Oscar-bait for their male leads). Both films are principally about marriages. In “Priscilla,” the wife is done with being seen but not heard. Considering Coppola’s prior film, “Marie Antoinette,” it’s no surprise that the director who showed audiences Marie’s thousand-window prison at Versailles was drawn to Priscilla’s shag-carpet cage one at Graceland. Both films contain a scene of the eponymous heroine gingerly taking the sexual lead, a forwardness that her partner finds emasculating. “Oppenheimer” can be seen as a precursor to the festival films in which aggrieved wives stand up for — and to — their faithless men, shifting the focus from male genius to marital power struggle.

The more movies I saw in New York, the more I found that the foregrounding of marital or relationship issues was not limited to the biopics. It was also present in “Poor Things,” with Stone as Bella, a cadaver rescued and reanimated by Dr. Baxter who replaces her brain with that of her unborn fetus, and who serves as surrogate father to his Frankenspawn. When Bella is of age, he betrothes her to his surgical assistant. But she wants to learn about the world first. What she learns about her mother’s marriage makes her look at wedlock with a gimlet eye.

It was also a current in Tran Anh Hung’s “The Taste of Things,” France’s entry for this year’s foreign film Oscar. It stars Bruno Magimel as a Belle Epoque epicure and chef besotted by Juliet Binoche, his cook of 20 years. He proposes marriage; she prefers their loving professional union to one recognized by the state.

We see it again in “Anatomy of a Fall,” Justine Triet’s enthralling whodunit about a successful German novelist, Sandra (Sandra Huller), who is suspected of killing her less successful French novelist husband by pushing him out the attic window of their chalet in the French Alps. To prove Sandra’s intent, the prosecutors dissect passages from her fiction and airs audiotapes that her husband recorded without her knowledge. At a certain point one wonders: Is she on trial for being a murderess — or an unsupportive wife?

Because drama is based on conflict, marriage has always held a strong appeal as a cinematic motif and plot device. Its potential for enlarging while examining real life are particularly layered in the thought-provoking treatments found in “Maestro, “Priscilla,” “Poor Things,” and “Anatomy of a Fall.” Of them all, ”Maestro” comes closest to my own experience of marriage as a continuum of attraction, buyer’s remorse, exasperation and periods of mutual connection and deep understanding. The film doesn’t take sides with either Lenny or Felicia Bernstein. The inference is that the culture of 1950s America was not flexible enough for the pair to create their own creative, emotional and sexual worlds. The New York Film Festival is an apt venue for this critique, since the strictures of midcentury culture were also the impetus for its creation in 1962.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.