J. Edgar Hoover’s ‘Suicide Letter’ to Martin Luther King Jr. Is Even Worse Than We Knew

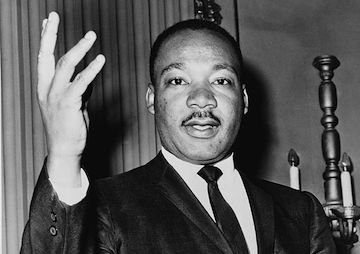

Half a century ago, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover had what he clearly considered to be a big problem in the form of civil rights galvanizer Martin Luther King Jr. This 1964 photo of Martin Luther King Jr. was taken by a New York World-Telegram & Sun photographer. Wikimedia Commons

This 1964 photo of Martin Luther King Jr. was taken by a New York World-Telegram & Sun photographer. Wikimedia Commons

Half a century ago, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover had what he clearly considered to be a big problem in the form of civil rights galvanizer Martin Luther King Jr. In late November 1964, one of Hoover’s underlings typed out a letter, posing as a disillusioned African-American excoriating King for his moral failings and calling for a reckoning, as Beverly Gage details in a report for The New York Times Magazine.

By that time, King had become a renowned leader occupying a very visible stance on the global stage; as Gage notes, he was months shy of receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, and Congress had passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 a few months prior. So Hoover and his deputy William Sullivan produced another indirect plan (attempts to stage a smear campaign in the press hadn’t been so productive) to tear King down.

“King, look into your heart,” the letter says. “You know you are a complete fraud and a great liability to all of us Negroes.” Gage, an American history professor at Yale, sums up the letter thusly in her write-up:

The word “evil” makes six appearances in the text, beginning with an accusation: “You are a colossal fraud and an evil, vicious one at that.” In the paragraphs that follow, the recipient’s alleged lovers get the worst of it. They are described as “filthy dirty evil companions” and “evil playmates,” all engaged in “dirt, filth, evil and moronic talk.” The effect is at once grotesque and hypnotic, an obsessive’s account of carnal rage and personal betrayal. “What incredible evilness,” the letter proclaims, listing off “sexual orgies,” “adulterous acts” and “immoral conduct.” Near the end, it circles back to its initial target, denouncing him as an “evil, abnormal beast.”

The unnamed author suggests intimate knowledge of his correspondent’s sex life, identifying one possible lover by name and claiming to have specific evidence about others. Another passage hints of an audiotape accompanying the letter, apparently a recording of “immoral conduct” in action. “Lend your sexually psychotic ear to the enclosure,” the letter demands. It concludes with a deadline of 34 days “before your filthy, abnormal fraudulent self is bared to the nation.”

“There is only one thing left for you to do,” the author warns vaguely in the final paragraph. “You know what it is.”

Although more general information about Hoover’s “suicide letter,” as it has come to be called, was made public for decades, sizable portions of it were redacted — until Gage made the kind of discovery that those in her field dream of: “This summer, while researching a biography of Hoover,” she says in her Times story, “I was surprised to find a full, uncensored version of the letter tucked away in a reprocessed set of his official and confidential files at the National Archives.”

Gage draws a timely link across five decades by pointing out that “the letter offers a potent warning for readers today about the danger of domestic surveillance in an age with less reserved mass media.”

Scary and true. Now, if only we could find out about more of these incidents closer to the time when they actually happen.

–Posted by Kasia Anderson

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.