What Happens When Conspiracy Theories Go Mainstream?

Journalist and “Republic of Lies” author Anna Merlan explains how falsehoods spread, and whether there’s anything we can do about it. Infowars host Alex Jones. (Tyler Merbler Photo / Flickr )

Infowars host Alex Jones. (Tyler Merbler Photo / Flickr )

Conspiracy theories can seem so absurd they’re almost funny: major politicians are actually 12-foot lizard people, the U.S. government was responsible for 9/11, the fluoride in our drinking water is there not to strengthen our teeth, but to control our minds. It’s easy to dismiss such ideas as nonsense.

Sometimes, however, theories escape the confines of online message boards and social media and turn dangerous, even fatal. No one laughed when a man named Edgar Welch drove from North Carolina to Washington, D.C., and fired shots at innocent people in a pizzeria because he was a believer in “Pizzagate,” a theory spread by people like right-wing radio show host Alex Jones that Hillary Clinton and her close advisers ran a pedophilia ring out of the pizzeria’s basement. There also was no laughter when James Alex Fields drove his car into a crowd at a 2017 white supremacist gathering in Charlottesville, Va., killing anti-racist protester Heather Heyer.

As journalist Anna Merlan explains in her new book, “Republic of Lies: American Conspiracy Theorists and Their Surprising Rise to Power,” “While conspiracy theories are as old as the country itself, there is something new at work: people who peddle lies and half-truths have come to prominence, fame, and power as never before,” thanks to the Trump administration’s outward embrace of some of their biggest boosters.

As a reporter for Jezebel and Gizmodo, Merlan covered various conspiracy theories, including those held by white nationalists, UFO enthusiasts and anti-vaccine advocates. After one story, for which she attended a conspiracy-themed cruise aptly called “The Conspira-Sea,” Merlan writes, “I tried to forget about it. I had done a kooky trip on a boat, the kind of stunt journalism project every features writer loves, and it was over. Conspiracy theorists, after all, were a side show.”

Ater the 2016 elections, however, such theories went from cultural sideshow to political main event. People like Michael Flynn, who spread Pizzagate theories on social media, was briefly the national security advisor and had the ear of President Trump, for example.

“Republic of Lies” is an illuminating, occasionally scary book that explains conspiracy theories, how they spread, their history in the United States, and what, if anything, can be done to prevent them. Truthdig spoke to Merlan by phone to learn more.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Ilana Novick: Your book starts with a story about attending “The Conspira-Sea,” a conspiracy-themed cruise featuring UFO experts, Sandy Hook “truthers” [people who believe that the 2012 mass shooting never happened], and anti-vaccine advocates, among other groups. What made you decide to go from one story about a cruise to a whole book about conspiracy theories?

Anna Merlan: The impetus was Trump’s election. When I went on the cruise, it was very much with the understanding that Trump was sort of reviving a lot of interesting conspiracy theories and a lot of energy in conspiracy communities, because they thought that he was going to break open all these dirty secrets and dark schemes. I had also written about the ways that he was generating a lot of excitement among white supremacists, and so I was thinking about what all those communities were going to do when he lost, and then he didn’t. It seemed like a valuable time to really consider what I did and didn’t know about this country, and also the ways that these communities that I had thought of as fringe were taking a more central role in our politics and our culture.

IN: You focus on multiple groups and their conspiracies, ranging from white supremacy to UFOs to Pizzagate. How did you decide which groups to profile, and why?

AM: I really wanted to do a survey, first of all. I didn’t want to focus narrowly on one conspiracy community, because I was aware of the diversity of views in that world. I also felt like all of these groups had something to teach us about the way that the history of secrecy in politics and government, and the history of inequality in America, are reflected in conspiracy communities. The only group I would say that I didn’t really spend any time with—well, there are two groups: climate change skeptics, which I wish I had done more with, and flat-earthers, which I didn’t, because I didn’t feel like I had a lot to learn about flat-earthers. Maybe I was wrong.

IN: In the book, you cite academic studies of conspiracy theorists and theories that found people who were disadvantaged—economically, socially, culturally—were more likely to believe in conspiracy theories. Now, it seems, they’ve reached the highest, most privileged levels of society, with even the president and members of his administration claiming they are victims of witch hunts and cover-ups. Why do you think that shifted?

AM: I think that one thing we know generally is that people who are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories believe themselves to be under threat. For some people, like black Americans, that threat is more real, and for others, like white supremacists, for instance, who believe that they are at risk of being invaded and put under Sharia law, that threat is not real. But certainly the sense of personal and economic and social instability is a predictor of believing in conspiracy theories. It’s interesting—the ways that even a belief that is not rational, like the idea that the government is going to break into your home and take your guns, does predispose you to believing in conspiracy theories.

IN: From the Pizzagate group that believes that Hillary Clinton and John Podesta have a pedophilia ring in the basement of a Washington, D.C., pizza place, to the UFO truthers who discuss sexual abuse at the hands of aliens, it seems that child abuse, and pedophilia in particular, is at the heart of some of these theories. Why do people get so obsessed with the idea of children being hurt as part of conspiracy theories?

AM: The oldest conspiracy theory about child abuse is the blood libel, which is the conspiracy theory that Jews were kidnapping and murdering Christian children to use their blood in matzo. The blood libel has been incredibly durable as a conspiracy theory. You hear it being repeated in literal form all over the world. You also see what I would argue are extensions of it, like the satanic panic and Pizzagate, which are both predicated on this idea of a powerful group of evildoers meeting in secret. I think some of it is that, in America, the suspicion of ritualistic abuse is never far away. I think it has something to do with the religious roots of this country. We tend to believe in a powerful, evil, satanic group of evildoers, and see that as literally possible. The other thing that I would argue is that if you believe that your ideological enemies are hurting children, there’s nothing that isn’t justified against them. I came to see that particular conspiracy theory as sort of a rhetorical justification for violence, because nothing is worse than hurting children, and nothing is not excusable if you are trying to prevent a child injury. If you’re trying to up the rhetorical stakes, that is a logical place to go.

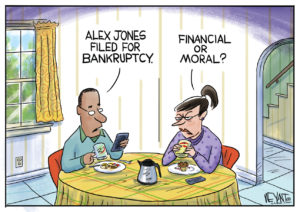

IN: Is that true even for people like Alex Jones, who promotes a crisis-actor theory—the idea that the school shooting at Sandy Hook never happened, or was a false flag designed to clear the way for the government to take people’s guns and attacks parents whose children died and survivors of that shooting?

AM: I think that he and other people who have promoted the crisis-actor conspiracy theory would argue that what they’re doing is important for nothing less than the fate of humanity. They are justified in attacking people who look like grieving parents, but who they would argue are not. The other thing, of course, is that with the crisis-actor conspiracy theory folks—Alex Jones and others—they’re trying to claim this gigantic conspiracy theory to stage mass shootings, and of course they can’t find the actual culprits because they don’t exist. The only people who are visible to them are the parents, are the survivors of these people who have died. It is both ghoulish and not surprising that they tend to fixate and fasten on those people, because they are the only people who are real people. They have never successfully made a case for who in government, for instance, is staging false flags. They obviously can’t call for any kind of drastic action against those people.

IN: You write that throughout its history, the United States has spied on civil rights leaders, performed sometimes dangerous medical experiments on unwilling participants, and otherwise abused its power, often trying to cover it up. Given that history, does the United States government bear any responsibility for the spread of many of the ideas you discuss?

AM: There are so many conspiracy theories that are based in a somewhat contorted but basically reasonable historical understanding of what the American government has done. There are a ton of medical conspiracy theories that really do refer back to a history of sometimes secret medical experimentation on unwitting, socially disadvantaged people, like inmates and children in state care. And there are a lot of conspiracy theories, even conspiracy theories about things like false flags, that do refer back to actual action by the American government and other world governments. So arguably, the thing that the U.S. government could do better to prevent the spread of conspiracy theories would be to be a more just and transparent government to begin with. That would have been great, but at this point, some of the sort of conspiratorial nature of the U.S. is almost like a form of generational trauma—that so many things that seem outlandish had been proven to be real over the course of American history that there is almost this permanent, unfixable sense of distrust and suspicion.

IN: I remember early coverage of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign seemed almost like a joke. This was despite the fact that he opened his campaign calling Mexican immigrants rapists, and promising a Muslim ban. Many people found him funny. Even as measles rates were trickling up, I remember some pundits brushing off anti-vaxxers simply because celebrities like actress and former co-host of “The View” Jenny McCarthy were promoting the theory that vaccines are dangerous. Does our mockery lead us to ignore the true danger behind these groups?

AM: Yeah, I think historically we have downplayed the role of conspiracy theories in American politics. And as you’re pointing out, when we do discuss them, a lot of times there’s a lot of mockery. There’s so many jokes about conspiracy theorists, including the sort of prototypical one, which is that they all wear tinfoil hats, right? And so it can make it really hard to assess when they are becoming genuinely influential or important. Because we know that they do tend to wax and wane in strength and importance throughout American history. And it’s an interesting balancing act, too. And it’s one thing that a lot of journalists who cover this stuff grapple with—how do you write about these things without either giving them more prominence or pretending they have any legitimacy, but also while genuinely trying to understand their importance and the sort of effects that they have? I think it’s really, really hard to assess. Something like QAnon I never thought would have become as large as it is.

IN: Can you talk a little bit about what QAnon is?

AM: QAnon is essentially an internet-based conspiracy theory that is focused on the idea that there is a secret, high-level Trump operative who is leaving clues about a future mass arrest of Trump’s opponents or some gigantic consequential action that Trump is about to take. And so this person calling themselves Q appeared on 4chan and started leaving these clues, which they called “crumbs.” And it became a really popular conspiracy theory among people who like the idea that Trump was doing a really good job and was not under any kind of investigation and was, in fact, preparing to arrest all of his political opponents and usher in this sort of glorious new age. And so there’s been a lot of attempts to figure out where QAnon came from—if it was a prank, if it was deliberately planted, or how exactly it came to be. But I think it can speak to the fact that internet-based conspiracy theories especially can spread in a way that is really surprising, even if they seem nonsensical to outsiders.

IN: Tell me about your experience covering white supremacist groups.

AM: I think that the sort of resurgence of open white supremacist communities in the United States is obviously something that has been fed by the politics and rhetoric of the Trump era. And I think it is very much tied to the resurgence in certain kinds of far-right conspiracy theories. I don’t think the two phenomena are separate. Also, white supremacists especially traffic in very old conspiracy theories, whether it’s the blood libel, Holocaust denial. They employ a lot of conspiracy theorist rhetoric. And so I wanted to spend time with those people to better understand how they fit into the conspiracy world. There were several white supremacist podcasters who just focus on conspiracy theory stuff and love talking about things like reptilians. There are a bunch of white supremacist folks who have gotten very engaged in the idea of tall lizards ruling the world. So, I would say that writing about them is hard, because the temptation to make fun of them is so strong, because they are really such a pathetic and comical group of people. But then, both in the book and in other times that I have interviewed white supremacists, the most alarming, upsetting thing is how young some of the people in those crowds are and this realization that there is a new generation of racists coming up all the time, who can find an ever-increasing justification for violence. The rally that I was at, as I write about in the book—one of the groups that was there with Vanguard America, who later attended the Charlottesville rally, and one of whose marchers, James Fields Jr., is the person who killed Heather Heyer by driving into the crowd in his car. So in a lot of ways, that particular section of the book for me was the point where I thought a lot about the ways that violence can be not unpredictable. It’s almost like it’s a place where I thought a lot about how I have to take people’s rhetoric seriously, even if by my assessment they look pathetic or stupid or disorganized. Those people were saying that they were looking forward to a violent confrontation with anti-fascists. They were really, really excited about it. They were disappointed that it didn’t happen in Kentucky. And arguably, if law enforcement communities had been paying more attention to those groups, maybe what happened in Charlottesville could have been avoided.

IN: How can journalists cover these groups without simply giving them an extra platform for hate speech and disinformation, both for the right, and even for the #resistance groups and Louise Menschs of the world who promote various falsehoods about the Mueller report?

AM: I’ve definitely seen a couple of examples recently of stories that I felt like were mostly just a platform for hateful ideas and weren’t super responsibly reported. And I would say I think the most important thing when we’re covering these groups is, rather than giving them an endless amount of space to explain their viewpoints and espouse their hateful ideas, I think it’s much more useful to understand the means that they’re using to organize, the avenues through which they’re spreading hate or disinformation, and, crucially, who is funding them. Some of the best reporting about some of these groups is about the ways that they are tapping into mainstream power and influence and money. So I do think that there’s value in covering these groups, but I don’t think there is value in covering youth groups just to say, “This is what they believe, and they have a lot of YouTube subscribers.” I think we need to go a little bit deeper than that.

IN: I’ve seen a lot of discussion in the media about intent, when it comes to people like Alex Jones, who are making money off spreading their ideas. I was wondering if you think it matters whether or not people like him believe what they’re promoting—if intent matters when their words lead their followers to do things like try to shoot up a pizza place or harass the parents of school shooting victims.

AM: That that is a very common question—whether Alex Jones or whomever believes what he’s saying. And I would argue, first of all, that that’s not really something that is [knowable] for us. We’re not omniscient, we’re not his spiritual confidant or his spouse or whatever. There are some things that are simply not knowable to outsiders. What I care about is what they have spent their time doing. Alex Jones, for instance, has had a 25-year career that is based around making outlandish claims that are very often about false-flag conspiracy theories. That was one of the earliest things that he did with the Oklahoma City bombing. So whether or not he believed that, we certainly know how much time he has invested in claiming it to be true.

IN: Looking ahead, do you think that there is anything to be done to combat the spread of these ideas?

AM: I think we know that conspiracy theories especially flourish during times of social upheaval, and when we are asking big questions about who we are socially and politically and what we want to be as a country or the world. And we also know that conspiracy theories flourish in climates where people feel dispossessed, locked out of systems of power. They don’t understand the institutions that are governing their lives and they can’t influence them. So I do think, as idealistic as this is, that if we put ourselves in the world of building a more just and transparent society, conspiracy theories will lose some of their grip. They’re never entirely going to go away, because they’re part of a free and open and sort of tumultuous discourse, but they don’t have to be what they are now, which is this increasingly sort of influential and often malevolent force.

IN: As we all witnessed during the 2016 election, social media was a critical part of the spread of conspiracy theories, on both the left and the right. What do you think about Facebook and Twitter’s attempts to deal with the spread of conspiracy theories on their platforms?

AM: Every social media platform has shown that they are really bad at policing themselves. All of their attempts, especially Facebook’s, but not just Facebook, has been incredibly confused. The rollouts have been really strange. The people that they choose to ban from their services and the people they allow to stay can often be completely bizarre. I think we’re seeing that a lot of social media companies really just respond to public pressure and try to do whatever they can to get people to stop yelling at them. I also just fundamentally hate the idea of Facebook being left to police itself, for instance, because I think they’ve proven that they can’t do it. I think that social media bans in general inarguably make individual people less powerful. They are having an effect on Alex Jones’ audience, or Milo Yiannopoulos’ or Gavin McInnes’. Those people have less of an audience than they did, but I’m not sure that it actually does a whole lot to slow down the ideas that these people are promoting. I don’t think that there are fewer anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, for instance, or fewer anti-immigrant or white nationalists ones. I think it’s just sort of a matter of weakening individual people. So I don’t think that we have really come up with a satisfying explanation yet. And I would argue that a lot of the focus on social media bans is looking for sort of a technological solution to what is really a much more complex problem. So I think this is something we’re going to be arguing about for a long time, and I think, unfortunately, some of this is just coming far too late to begin with.

IN: On a lighter note, what is it about UFOs that makes them such an enduring obsession, even, as you note in the book, for politicians like former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid?

AM: I think that the belief in aliens is one of the oldest and largest and sort of most stable conspiracy subcultures there is, not just in the U.S., but around the world. And some of that is due to just the sheer number of people who have seen something that they can’t explain, the amount of information that we have about governments researching UFOs, sometimes in secret, as with the case of the Department of Defense program that was revealed at the end of 2017. And some of it, too, is just because I think a lot of people believe that we are not alone in the universe, and are keenly interested in the idea of finding out who else is out there. At its most benign end, UFO and alien subcultures are really kind of a positive thing, because they really have to do with human curiosity about the rest of the universe and a real desire to look beyond what is going on in our day-to-day lives and reach out and touch something bigger and more mysterious than us. So, I have to say that my time with UFO books is definitely the most restful, and in some ways made me the most optimistic about the future of this country.

Your support matters…

Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.