Our Gang Problem Is Bigger Than We Think

The word "gang" has often been associated with groups of poor young men of color. But the recent deadly shootout in Waco, Texas, among five largely white motorcycle clubs has drawn attention to the fact that gangs come in a variety of forms and colors. Fraternities, sports fans and even the police and military bear many of the same hallmarks.The recent deadly shootout in Texas, among five largely white motorcycle clubs, has drawn attention to the fact that gangs come in a variety of forms and colors. Police detain and watch members of various motorcycle clubs outside the Twin Peaks restaurant in Waco, Texas, where a shootout this month left nine dead. (AP / John L. Mone)

Police detain and watch members of various motorcycle clubs outside the Twin Peaks restaurant in Waco, Texas, where a shootout this month left nine dead. (AP / John L. Mone)

It was not long ago that gang violence was considered the scourge of urban cities in the U.S. The mantra of the 1980s, that “America has a gang problem,” was an invocation used to justify excessive policing in poor communities of color and led to reams of research papers on how to solve the problem. Many nonprofit organizations that were focused on gang prevention methods emerged. Almost all of these efforts centered on young black men (and to a lesser extent on young Latino and Asian American men).

But the May 17 Waco, Texas, shootout among five largely white “outlaw motorcycle gangs” (OMGs) has drawn attention to the fact that gangs come in a variety of forms and colors. A researcher named Harold Pollack who studies street gangs in Chicago said about the Waco shootings, “I have never encountered a gang incident in Chicago remotely like this. The number of perpetrators involved—not to mention the nine deaths—far exceed the typical urban gang-related shooting.” America does indeed have a gang problem — just not the one to which our thinking is usually restricted.

After the Waco incident, many commentators complained about the double standard in the policing, as seen in photographs of the incident. The mostly white bikers were not roughhoused nearly as much as African-American protesters accused of rioting in cities like Baltimore and Ferguson, Mo. But in addition to that double standard likely being the result of racist policing, something else may have been going on. One of the bikers arrested was a retired police detective from San Antonio. He also happened to be one of the few African-American bikers at the scene.

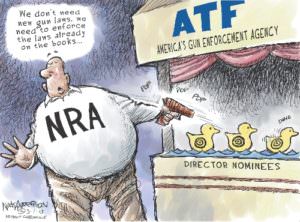

A secret report by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), titled “OMGs and the Military 2014,” was leaked to The Intercept. It detailed how police officers, senior members of the U.S. military and even the Defense Department are among members of OMGs. The Justice Department is apparently tracking more than 100 such people with ties to the U.S. government who operate in these dangerous biker gangs. According to the report:

“[P]articular OMGs and their support clubs continue to court active-duty military personnel and government workers, both civilians and contractors, for their knowledge, reliable income, tactical skills and dedication to a cause. Through our extensive analysis, it has been revealed that a large number of support clubs are utilizing active-duty military personnel and U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) contractors and employees to spread their tentacles across the United States.”

The word “gang” has wrongly come to be associated primarily with groups of poor young men of color. But those demographics are among the most vulnerable and persecuted groups of people in the U.S., in terms of economic clout, access to quality education and jobs, and police targeting. A recent New York Times report asked “How Do You Define a Gang Member?” making the case that so-called gang enhancements for sentencing were being disproportionately applied to young men of color based on circumstantial evidence. Gang enhancements are additional months of prison time that can be added to a convict’s sentence simply by virtue of appearing to be a gang member.

In fact, in California, “Black and Latino inmates account for more than 90 percent of inmates with gang enhancements; fewer than 3 percent are white.” While there is no doubt that organized gangs like the Crips and Bloods have a horrific history of bloodletting and violence, we would do well to identify other types of gangs that get off far more lightly.

The Justice Department has a lengthy definition of gangs, the first part of which is:

an association of three or more individuals … whose members collectively identify themselves by adopting a group identity which they use to create an atmosphere of fear or intimidation frequently by employing one or more of the following: a common name, slogan, identifying sign, symbol, tattoo or other physical marking, style or color of clothing, hairstyle, hand sign or graffiti. … the association’s purpose, in part, is to engage in criminal activity and the association uses violence or intimidation to further its criminal objectives.

White supremacist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan and Aryan Brotherhood clearly fall into this category, as even the government and most Americans agree. In recent years there have been upticks of violence from such gangs, commonly referred to as hate groups. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, nearly 800 such groups operate across the nation.

In fact, as this 1987 ATF report on OMGs found, the groups historically “allow[ed] only white male membership, which is in keeping with their strong white supremacy philosophy.” So OMGs have had common values with the likes of the KKK.

But what if we examined other groups through the lens of the government’s definition of gangs? Given the spate of brutality, violence, corruption and callous indifference to public well-being observed in police departments across the country, members of law enforcement, who often observe a strict sense of loyalty and allegiance to one another, ought to be seen as gangs. Rather than bandanas or patches, they wear uniforms. So serious is the problem of police brutality in the U.S. that a United Nations Committee on racial discrimination recently called out “[t]he excessive use of force by law enforcement officials.”

The various arms of the U.S. military also act like gangs in “adopting a group identity” through clothing, haircuts and slogans. Given the extent of crimes the U.S. military has committed through airstrikes on civilians, as well as the torture, rape and murder of prisoners, the U.S. Army, Navy, Marines, Special Forces and other arms of the military certainly act like organized criminal gangs.

Even mercenary groups involved in military operations, such as Blackwater (now called Academi), qualify as gangs. Award-winning journalist Jeremy Scahill detailed the bloody crimes and misdeeds of the company in his book “Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army.” In April, four members of Blackwater were convicted in the killing of more than a dozen Iraqis and sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

There are many other types of groups that fit the bill, most of them less violent than the police and military. Research papers such as this one have explored comparisons between street gangs and fraternities on U.S. college campuses. Citing the rampant drug use and dealing, as well as sexual violence and rape, documented among fraternities, the author refers to them as “the gangs of the United States’ elite” and concludes that “Street gang members go to prison and elite gang members achieve success.”

Sports fans can also fit the definition of gangs, particularly when popular sporting events generate violent brawls. People who identify with their favorite sports teams wear identifying colors and symbols, and, as this paper points out, “too often fan behavior mimics that of street gangs.”

Gangs are a social phenomenon present in all societies, offering a sense of purpose to people who claim common ground with one another. But all too frequently, gangs devolve into mobs that foment senseless violence. The Nazis were gang members. So are ISIS and the Nigerian militant group Boko Haram. And in the U.S., not only criminal biker gangs and the KKK but also groups we do not like to think of in this way are gangs, such as police, the military, fraternities and sports fans.

As long as we keep singling out some gangs for criminalization over others, we will miss the criminal activity right under our noses.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.