The Sound of Wit

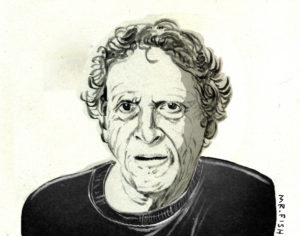

The late William Hamilton, a cartoonist for The New Yorker, made an unforgettable noise when he drew. "Darling, that terribly bright new young woman on your board—is she bicoastal or bisexual?" (William Hamilton)

"Darling, that terribly bright new young woman on your board—is she bicoastal or bisexual?" (William Hamilton)

William Hamilton already had a long-standing history as a cartoonist at The New Yorker when I met him, though it wasn’t his cartooning that caught my eye. I was a publisher at the time, and after reading a newspaper article he wrote, I approached him to write a book. The book was not meant to be, but we were.

Strikingly tall with a bohemian flare, William was a bit of a bad boy, and I was not unaware that he would be a precarious undertaking. Background is a poor substitute for character but shouldn’t be entirely ignored because, inevitably, it explains a thing or two. William’s background placed him in high society. Annoying to him was that high society lacked any meaningful cash flow. Because he recognized just how absurd money and society could be, the captions William wrote to accompany his drawings almost always hit the mark.

In ways having nothing to do society or money, we were wed on the Amazon River by the captain of a Peruvian supply boat. Not surprisingly, the legality of our marriage didn’t make it across the border, and we had to repeat our vows in the United States. Shortly before, William called me in my office: He wanted to discuss a personal matter that evening over dinner. “It’s important” was his ominous warning.

Resembling one of his drawings waiting for a caption, he and I sat facing one other across a restaurant table,

“If I tell you what it is, you won’t bolt, will you?” he asked, looking anxious.

“Of course not,” I managed to say. It wasn’t an entirely truthful answer.

“The thing is … I make a sound.”

I told him that, having been in each other’s close company for the year we were engaged, I was by now intimately familiar with all of the sounds in his repertoire. Admittedly, while some were distracting, none were disturbing to me.

“But you don’t know this sound,” he insisted. “Actually, it’s a noise I make when I draw. You’re not around when I draw, and when you are, I try not to make it.”

True: I left for my office early in the mornings before William sat down to draw, and I returned home in the evenings long after his ink and pen were put away. Apparently, he was able to suppress the noise during weekends, but the effort was taking its toll.

“Don’t worry” were my reassuring words. “I promise I won’t mind the noise.”

“I’m glad,” William said, relieved.

I was curious.

“What kind is it?” I asked.

“All I can tell you is that the couple living in the apartment below thinks I’ve set up a machine shop,” said the man for whom I would forsake all others.

The noise made a point of introducing itself the day we would be joined in legal matrimony at William’s family home in the Napa Valley. That morning—walking toward the room in which he was drawing—I heard what I assumed was a vacuum cleaner, but each step brought me closer to the realization that it was William powering the noise. Not right away, but eventually, William explained to me that the noise was how he moved his mind and pen in sync.

Two years ago last month, William was killed in a car collision—in a split second, he was gone. For me, he left behind our very tall son in possession of his father’s dry wit and nuanced sensibility. I can recall without much effort our three lives when they were happily combined. And, if I concentrate, I can still hear the noise that was William’s, and his alone.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.