Paul Krassner Gave a Shit About Everything

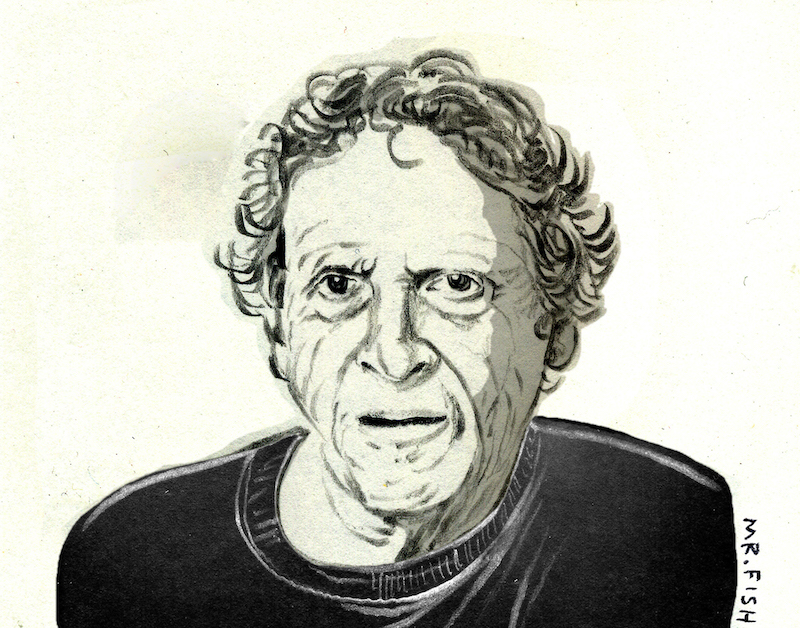

The late journalist and comedian, best known for co-founding the Yippies, was a force to reckon with at every age. Mr. Fish

Mr. Fish

“Irreverence is our only sacred cow.” —Paul Krassner

Paul Krassner died Sunday at 87, and more than anybody else in his generation, he lived his life demonstrating over and over and over again how the best way to save our country from the relentless onslaught of polarizing politics that buries our enthusiasm for a kinder and gentler society is with friendship and humor, pure and simple. “Trying to save the world is a banker’s mentality,” he once told me while we were eating grapes at his kitchen table, “which is why I like to spend my time paying attention.” He did that kind of thing all the time, to everybody he knew—that thing being to camouflage his wisdom in an ad-lib phrase, improvised pun or invented idiom, which he’d then deliver as if it were nothing, a harmless ball of bubblegum, maybe. Only after you’d spend the next hour chewing on what he’d said would you realize that what he’d given you wasn’t glib or trivial or disposable at all. Instead, he’d given you something you found yourself replaying in your head and wanting to share with others, the wanting to share part being precisely what brings meaningful cohesion to the multitude.

Of course, he always did claim that English was his second language, laughter being his first.

***

On a chilly Friday night in 2007, when most of L.A. was still shoving Kleenex balls into its pants and mouthing the words “Please love me” into its bathroom mirror, a 75-year-old man wearing a dirty, red satin baseball jacket, a black T-shirt emblazoned with a pot leaf the size of a spinning boomerang and hair like steel wool, said from the tiny stage of the M Bar, “I’d like to end on a note of hope, since I talked about a lot of negative stuff tonight.” He went on to discuss the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and how it had recently been moved from seven minutes before midnight to five minutes before midnight, midnight being the end of the world. “The good news,” he said, “is that scientists are people, just like the rest of us, and they’re probably just as neurotic as we are, so they probably set the clock to be 10 minutes fast—so it’s really only a quarter of.”

The room went crazy with applause, and then everybody went outside to have their cars retrieved by the strip mall’s valet service, while I stayed inside to watch person after person thank Paul Krassner for his performance—and for the work he’d done his whole life.

***

Krassner, a founding member of the Youth International Party (known as the Yippies), a Merry Prankster, a contributor to Mad Magazine, the ninth member of the Chicago Seven and the father of the underground press, began publishing The Realist—which is now being called the “Charlie Hebdo of American satire,” and which writer Terry Southern referred to as “the first American publication to really tell the truth”—in 1958 and stopped in 2001, finally upstaged by real-world events whose tragedy and absurdity trumped any and all satirical contrivances. After all, it was during that year, on Sept. 11, that the United States was attacked by 19 men with box cutters who ended up killing nearly 3,000 people. The date of the attack also happened to be the 126th anniversary of the initial publication of the very first newspaper comic strip in the U.S., “Professor Tigwissel’s Burglar Alarm.” It was published by the New York Daily Graphic newspaper, whose offices had been located some 5,000 feet away from the site of the World Trade Center.

Appropriately, the 1875 strip depicted a self-aggrandized egomaniac who attempts to protect himself from the threat of a home invasion by stockpiling excessive firearms and weaponry and installing a foolproof security system designed to prevent a surprise attack. In the comic strip, the firepower and security system don’t work, and Professor Tigwissel is attacked, but he arrogantly claims success afterward. He promises to patent his device to perpetuate the notion that we are best protected by the machinery of our paranoia and a weaponized mistrust of the world, rather than by a less hysterical adherence to truth, justice, humanitarianism and mutual cooperation. Such was the premonitory power of the cartoonist in the late 19th century, and such was the sickening plunge of real life into the realm of gruesome fantasy many years later, that rendered the satire of The Realist no longer allegorical, but literal—literalism being to allegory what a real fire is to a crowded theater.

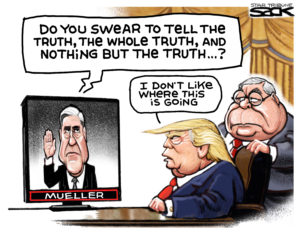

Specifically, where there once existed a well-informed, anti-authoritarian audience for satire, 21st-century Americans became passive consumers of inconsequential burlesque masquerading as satire. People assumed corporate-sponsored jokes that merely used political personalities and circumstances as fodder the same way that slapstick used seltzer bottles and baggy pants were somehow the same thing as sharp and unforgiving criticism by uncompromising freelancers for the deeper purpose of revealing political and social injustices and commenting on them in a way that engenders more psychic pain than physiological pleasure. The idea became that humorists in search of laughter alone over frank and honest outrage are not satirists for one simple reason: Mirth cripples rage, and rage is necessary for the beating back of political, cultural and religious bullshit in service of change.

As the No. 1 progenitor of all the alternative and underground publications that followed it, The Realist taught us that the best way to rescue a panicked society from drowning is not to throw it a life preserver, but to teach it how to swim.

***

I first met Krassner in 2007 at the M Bar in the crappy New Jersey section of Hollywood at the corner of Vine and Fountain. The bar was a very dark hole crammed into an enormous, two-story, L-shaped concrete monstrosity that has a Jewish deli, a Thai take-out place, an Italian take-out place, a Mexican take-out place, a Ramen/Japanese take-out place, a panini/tapas take-out place, a Cuban take-out place, a “European food” take-out place and a place with the words “A-1 Therapy” written on the door in a font only slightly more professional looking than masking tape. The foil covering the windows at A-1 Therapy suggests that it is a place that grows lizards or baked potatoes.

I had known his work from my college days in the 1980s, when I used to cut class and travel back home to pour over old copies of The Realist at an anarchist bookstore called Wooden Shoe Books in Philadelphia. In many ways, Krassner gave me my career as a cartoonist by both proxy and demonstration. When it came to the politics of being a smartass, he was the one consistent practitioner of prankster journalism, social commentary and political satire that, because of his relentless presence on the scene, gave some measure of credibility to the First Amendment and, yes, democracy, itself.

When Jack Weinberg said, in 1965, not to trust anybody over 30, Krassner was 33, an old, old man, and certainly an exception to the adage. With the gargantuan reputation of his magazine, The Realist—the flagship publication of the radical left at the time, perhaps of all time, and indispensable rag to the hemorrhaging heart of the Vietnam War-addled counterculture—he had established himself as the Walter Cronkite of the underground press and was considered the most trusted investigative satirist working in Amockrica.

“The irony is that I’ve always tried to uphold the virtues of the Constitution and I never took an oath to do it, while [the politicians I target] did take an oath, and they’re the ones trying to destroy the Constitution,” he told me at lunch in Santa Monica six hours before he stepped onto the M Bar stage. Amazed at the clarity of his mind and the animated enthusiasm with which the septuagenarian still seemed to give a shit about everything, I asked him how he’d been able to survive while so many of his contemporaries, like Timothy Leary, Lenny Bruce, Ken Kesey, Terry Southern, Hunter S. Thompson, Allen Ginsberg and, most notably, his fellow co-founders of the Youth International Party and co-conspirators in the Chicago Seven Conspiracy trial—Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, who John Lennon called the Mork and Mindy of the ’60s—had died. “Simple,” he said. “I’ve never taken any legal drugs.”

Having left Los Angeles in 2000 to live in Desert Hot Springs, a hundred miles away, he was only in town to do the one-nighter at the M Bar. “I’ve never played a strip mall before,” he said. “I played the Brentwood bakery once, and anybody who came got a free pastry.” I asked him if he missed Los Angeles. His wife, Nancy, who was sitting with us, said yes enthusiastically. He gave me this answer later, standing in the spotlight a mere 40 feet from A-1 Therapy.

“Desert Hot Springs is not like L.A.,” he said. He explained how every clerk at every retail shop he patronized in his new hometown never failed to remind him at the conclusion of every business transaction to “have a nice day!” Have a nice day! Have a nice day! Have a nice day!—it followed him everywhere. Have a nice day! “Just on the way over here tonight,” he said, capping a water bottle he’d just taken a swig from, “I bought this bottle of water from a girl who was sitting behind a cash register, looking really sullen. I figured that here was my chance to, you know, make her feel good with everything that I learned in [Desert Hot Springs]. So, after I paid for the water, I looked at her and I said (gleefully), ‘Aren’t you going to tell me to have a nice day?’ ‘It’s on the fucking receipt!’ she said.” It gave him the biggest smile I’d seen on his face all day.

I left the club at 9:15 p.m., while there was still a line of people hoping to shake hands with Krassner. Stepping into the parking lot, I noticed that there was still a tiny bit of pink light clinging to the horizon and, with Krassner’s Groucho Marxism still ping-ponging around inside my mood, I decided to imagine that I was looking at the dawn and hoped that with any luck I would always be that mistaken about the dark.

What follows is a portion of one of the last conversations I had with him.

Mr. Fish: Besides attracting many of the most celebrated writers as contributors during its more than two decades in print—writers such as Norman Mailer, Ken Kesey, Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Heller and Avery Corman—The Realist also attracted a number of famous cartoonists to its pages. In addition to running Ron Cobb, Wally Wood, S. Clay Wilson, Charles Rodrigues, Art Spiegelman and Dick Guindon, who were among the top counterculture cartoonists of the 1960s, you also published a handful of more mainstream cartoonists whose work typically appeared in The New Yorker, Esquire, Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping and the Harvard Business Review. These were cartoonists who wished to publish edgier work on racism, birth control, the Vietnam War, censorship and women’s rights, which were topics that conventional magazines would never run. These cartoonists included Jules Feiffer, Mort Gerberg, Sam Gross, Frank Interlandi, Lee Lorenz and B. Kliban.

Paul Krassner: Right—remember, this was a time when there were cartoonists who were basically gag writers and cartoonists who were more interested in satire. Gag cartoonists like [those] who drew for The New Yorker made a lot more money than cartoonists like Cobb or Guindon. But [publishing] The Realist was never about making money, and neither was creating [satirical cartoons] that attacked the establishment.

MF: That’s why Cobb eventually had to quit doing it and go into designing spaceships and aliens for fucking Hollywood. It’s kind of heartbreaking.

PK: That’s what Lenny Bruce’s Lone Ranger was about—saving people and not expecting any reward for doing it.

MF: Can a gag cartoon sometimes serve the same purpose as a satirical cartoon?

PK: No.

MF: Why not?

PK: Because with satire, there will always be people who believe that it’s real, that the government is capable of the most outrageous things, which, of course, it is. So, in a way, [satire] actually informs people of a danger that’s real by attracting their attention to the truth with a lie. The New Yorker doesn’t do that.

MF: Because you have interviewed and/or published so many of the most important and influential thinkers and artists of the mid-20th century, I thought it might be smart to get your perspective on why, when it comes to contemporary culture, artists and writers and poets and painters and social philosophers, either by accident or by deliberate design, have been removed from the national debate about who we are as a species and where we are going as a society.

PK: [Partly the trouble] is that so much of what passes for satire nowadays isn’t real satire, at least not in the traditional sense. For one thing, it isn’t even ironic—it’s Sarcasm 101. Audiences will applaud for name-calling as a replacement for wit.

MF: I agree—real satire begs a conversation to happen after the joke has been told. Not only that, [it] assumes that a conversation had been going on previous to the telling of the joke. [Satire] assumes that the audience is there to do at least half of the heavy lifting when it comes to getting the punch line and recognizing the irony or the hypocrisy of whatever is being lampooned.

PK: And that’s the subjective side of humor—all that [foreknowledge] that makes satire work. There are a lot of factors to consider when building strong satire. But there’s also the objective side [of humor] that, if you can get it in with the subjective side, it really makes for [a good joke].

MF: The difference between a clown eating a shit sandwich for no reason and the pope eating a shit sandwich for some reason.

PK: Yeah. In 1978, I went with my daughter, Holly, to Ecuador on a shamans and healers expedition, and we stayed with primitive Indians and took ayahuasca—I should say, indigenous Indians, because they looked at us as if we were the primitive ones. Anyway, we lived for a while with three generations of Chiapas Indians. There were about 15 people in our group, and one of them was an anthropologist, but after a while it became clear that we were the subjects and [the Chiapas] were the anthropologists. I remember watching a mother who was talking to us and how she was playing with her naked son’s penis and how there was no internalization of inhibited social structures, at least none that I could relate to. [Similarly], they would watch us brushing our teeth or doing Tai Chi and wonder what the hell we were doing, you know. It was peculiar to them, like we were Martians who had dropped out of the sky. Regardless, I had these bright green sunglasses, and I let everybody try them on, and they all laughed at each other because [the visual] had elements of incongruity. They didn’t know our language, but they knew what they felt in their gut, which was that it was silly. So, while so much of American humor has a lot to do with taste, and so much satire has an agenda that serves either the right or the left, there’s a primal sense of humor that resonates with people because it transcends culture and is universal [to everybody].

MF: Right, that’s the appeal of slapstick, I guess. Maybe it’s even the appeal of much of commedia dell’arte, stereotypes being much more closely related to our lower base functions [than our higher]. Still, what scares me is how society can sometimes misconstrue the ease of experiencing that primal sense of humor you mentioned as being the only genuine humor there is and, therefore, the only humor we should recognize. Way too often I hear pundits complaining that satire, like “The Daily Show” or The Onion or “South Park,” is not real humor because it parodies political grandstanding and hate speech and religious buffoonery, that sort of thing. In other words, I’m uncomfortable when the definition of humor excludes irony and critical thinking and dissent because it is assumed that people are way too stupid to get the joke. I hate the notion that laughter cannot be used as a teaching tool and that censorship is somehow preferable as a mode of communication.

PK: Exactly. With The Realist, I would never label an article as either journalism or satire because I didn’t want to deprive the readers of the pleasure of discerning for themselves what was true and what was an extension of the truth.

MF: I remember you saying that for years you received letters from people who thought that your famous piece about the Kennedy assassination was real investigative journalism.

PK: I still get them!

MF: And that speaks to how absolutely bizarre reality can be in comparison to satire. The fact that you were able to write something that was so fantastic and so ludicrous and still have people confused about whether it was fiction or nonfiction, even 50 years later, is really telling about how the world works. It reminds me of an argument that I have with 9/11 conspiracy theorists all the time. I’m forever telling them to expand their rage and distrust of the government beyond what happened on September the 11th, because if you’re looking for examples of how distrustful Washington is and how the president is a complete asshole [who is] able to commit unforgivable crimes against humanity and [who can] kill thousands of innocent people for purely political reasons, just look at his domestic policies against poor and underprivileged people living in the country right now. Look at his foreign policy, which is not secret and is published in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal every day. For fucksake, beginning with the sanctions against Iraq, implemented by the first Bush in ’91, straight through until now, we’re responsible for millions of deaths that could have been avoided. Then there’s Clinton’s bombing of the Sudanese pharmaceutical plant [in 1998] that destroyed the lives of millions of people. The point is, by sitting across the street from the White House in a windowless van with your night binoculars trained on shadows you see through the curtains, you risk missing what is already happening in broad daylight, which is stuff that is way worse than what you’re trying to uncover.

PK: Right, like looking for dirt on Eva Braun.

MF: (laughs) Exactly!

PK: But, yeah, getting back to your point about satire, it is much harder to create satire when the world itself is naturally satirical.

MF: So then we have to ask the question of what jokes do. Do jokes spotlight what is already funny about the world or do jokes reinterpret the world and create something funny about it? Is it funny, for example, that lawyers are cheats and politicians are liars, or is it unfunny that lawyers are cheats and politicians are liars, and jokes help us deal with the misery of that reality? Does satire defang the monsters that we feel most threatened by or does satire give us sanctuary from those monsters, the same way that being locked up in a prison cell protects us from the terror of having to keep up with a mortgage and maintain a lawn? Which came first, the chicken or the rubber chicken?

PK: I don’t know that there’s an answer to that.

MF: Well, I do feel that satire has opened my eyes to certain things, but I’m not sure if it is my inner eye or my outer eye that was opened.

PK: I remember when I was a counselor at a summer camp and how they would show Charlie Chaplin movies and some counselor would inevitably get up and say, “Now the deep social message that Chaplin was trying to convey in the scene when he had to eat his shoelaces …” You know? We were all talking about why we laugh, and the kids were saying, “I thought he had a funny walk.” So, again, there’s that innate sense of humor that we can all tap into and maybe that defangs the monster.

MF: At least the monster that we project onto the world with our own pessimism. That was what John [Lennon] and Yoko [Ono] said when the press accused them of not taking the protests against the Vietnam War seriously enough. They said that they were willing to be the world’s clowns [during their Bed-In event], the idea being that humor is anti-violent. They made the point that you’re unlikely to attack somebody else, much less kill them, when you’re having a laugh.

PK: And yet satire is often called a weapon.

MF: Which brings us back to the precariousness of jokes designed to do something more than just make people laugh. A satirist is either funny when you agree with him or downright mean when you don’t. In fact, there are a lot of people who won’t even call satire art, precisely because it involves [political subject matter]. They’re the same people who insist that the surest way to fuck up a piece of art is to inject politics into it.

PK: There again, it’s all about the individual perception. Some people need politics injected for it to qualify as art.

MF: I agree. There’s also a pretty good argument for how injecting art into politics can fuck up politics—at least how one relates to politics on a personal level. The example that I always give is how watching “The Daily Show” and “The Colbert Report” can fool a person into thinking that he or she is being politically active when he or she isn’t. It’s because watching TV is a private act and engaging in political activity is a public [act], and when somebody is at home watching a television show, though he or she might be agreeing with jokes about, say, the criminality of the president or the injustice or a piece of domestic or foreign policy, he or she is not doing anything about it. In that way, laughter can deter political activity.

PK: I know what you mean, sure. On the other hand, [my wife] Nancy memorized Mort Sahl’s first album [“The Future Lies Ahead,” 1958] when it came out, and when you memorize something like that, you really pick up on a lot of nuance about how the country works. You absorb a lot of critical thinking; it’s a very subtle process. And that can be politicizing and make you politically minded at the very least and make you behave a certain way. I remember when I lived in San Francisco and attended the annual Comedy Day in the Park. This was in the ’80s, in Golden Gate Park, and there was a long string of comedians, and the only thing I remember from the day was a guy standing up and saying, “Isn’t Reagan an asshole?!” And the audience [went] crazy with applause and yells and the guy [said], “Oh, so you like the political stuff.” So there are different standards of what being politically minded means. Sometimes you can be political without naming names. Guys like Mark Twain and H. L. Mencken and Will Rogers were all political.

MF: And so was Bruce, though not overtly so.

PK: Lenny Bruce died to make it safe for Jon Stewart to get laughs by saying words he knows will get bleeped out.

MF: Further proof that Bruce didn’t die for our sins, but because of them. God, I miss that guy

PK: Yeah, me too.

MF: I guess what I worry about is the ability of a good political joke to diffuse the rage that a person might have for a politician who deserves all the vitriol that we can throw at him. Sometimes I think it’s more important to embrace the discomfort that comes from being pissed off about something than to have your disdain obliterated by the relief you get from laughter.

PK: Lenny and I used to talk about this stuff all the time, and his position was that people don’t like to be lectured at. He believed that if you [could] make somebody laugh with a joke that [had] some truth about society embedded within it, the fact that they’re laughing indicates that their defenses are down and that they’re more likely to consider the information you’re telling them. The joke makes it impossible for a person to guard against [the wisdom of the argument] you’re presenting.

MF: Plus, if it’s a good joke, it will bear repeating to more and more people, and the information can become viral that way. It’s like a catchy tune that you want to hear again and again.

PK: Right—I’m relatively jaded, and if something really stirs me, either a contradiction or an absurdity or a horrible cruelty that has been euphemized, and that will set my EEG off, then I’ll want to create a satire that crystalizes that contradiction or whatever it is, and I’ll want to share it with people. Then, if it’s funny, those people will want to share it, too. It’s how The Realist grew. Steve Allen was the first subscriber, and he gave a bunch of subscriptions to a lot of other people, including Lenny Bruce, and then Lenny sent out a bunch, and the magazine really took off that way.

MF: Of course, when it comes to the catchiness of tunes that people want to hear again and again, taste can sometimes trump nutritional value. There’s the two-step, but there is also the goose step.

PK: Right. Now that you mention it, I think “Malthusian” was the word they used to use before “viral.”

MF: Of course—yesterday’s torture is today’s enhanced interrogation.

PK: And dead babies [have always been] collateral damage.

MF: And, thanks to people like you and Lenny Bruce, “Fuck the government” will always mean “Fuck the government.”

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.