Korean War Games Are No Game

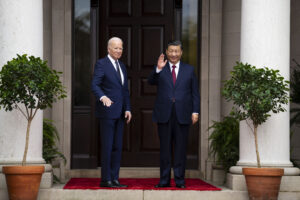

The time has come to cancel them for good. U.S. and South Korea soldiers conduct a river-crossing exercise in Seoul, South Korea, in 2016. (Sgt. Christopher Dennis / U.S. Army)

U.S. and South Korea soldiers conduct a river-crossing exercise in Seoul, South Korea, in 2016. (Sgt. Christopher Dennis / U.S. Army)

The remarkable recent diplomatic overtures from both North and South Korea present the United States with an extraordinary opportunity to step back from the nuclear precipice. And there’s one single act—or more precisely, the absence of an act—that Washington, D.C., can undertake to seize that opportunity.

In one of several surprising concessions, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un indicated to South Korean officials that he would “accept” the resumption this spring of the annual U.S./Republic of Korea joint military drills which the two countries have conducted together for many years. Nonetheless, the best way now to pursue an enduring Korean peace is to cancel these American and South Korean war games. Not just this spring. Forever.

During his meetings with South Korean officials, Kim offered to engage in a “heart-to-heart” dialogue about a normalization of relations with the U.S. He suggested that North Korea would be willing to freeze both its nuclear testing and its missile testing. He said that if the United States would remove its military threats and guarantee “the security of its system,” North Korea would then possess “no reason to retain” a nuclear arsenal at all. And finally, in what would be an unprecedented event, Kim offered to meet directly with the American president.

President Donald Trump immediately accepted that invitation. But the next day, predictably for this chaotic administration, White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders said that such a meeting could take place only if North Korea first undertook unspecified “concrete and verifiable actions.” For those old enough to remember the Cold War, this concatenation calls to mind President Ronald Reagan’s agreement with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev at Reykjavik in 1986 to eliminate all the world’s nuclear weapons by the year 2000—only to be frantically talked out of it by his horrified advisers.

Despite these game-changing initiatives, Washington and Seoul are still on course to launch their huge annual joint military drills in April—the largest in the world—known this year as “Key Resolve/Foal Eagle” (whatever that means). In the past, these war games have included the participation of more than 200,000 personnel, the dispatch of aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines and nuclear-capable strategic bombers to the region, and the simulation of “regime decapitation operations” directed specifically at Kim Jong Un.

But the fundamental fact to recognize about these particular drills is that they serve absolutely no military purpose. The U.S. possesses perhaps 1,000 times the conventional military capability of North Korea. Imagine a fifth-grader taunting a robust high school linebacker in the gym. Instead of sneering at the insolent brat or simply ignoring him, however, the linebacker is busily working the speed bag. Why? “Because I have to be on my toes in case this ever turns into a real fight.” No, high school linebacker, you don’t have to be on your toes. You don’t have to work the speed bag. You can take the fifth grader.

Just as the United States can take North Korea. One doesn’t have to be a retired American general or a CNN defense intellectual to understand that if any kind of shooting war starts, the United States could destroy the North Korean military and defeat the North Korean regime within the space of a week.

Now, yes, North Korea could inflict vast damage before that point is reached. Long before North Korea had secured the nuclear deterrent it now appears to possess, it fashioned for itself a decidedly low-tech “ordnance deterrent”—more than 10,000 artillery tubes and rocket launchers, just across the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and pointed directly at Seoul and its 25 million inhabitants. It’s the largest artillery force in the world, and the North Koreans could start firing away seconds after hostilities commenced. North Korea also may possess both chemical and biological weapons arsenals. And, in the classic “use them or lose them” dilemma of the nuclear age, North Korea might successfully launch nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles toward South Korea, Japan, Guam, Hawaii and perhaps even the continental United States before the U.S. could take them out. These countries cannot, of course, accept the detonation on their territory of a single one.

The thing about those existing North Korean deterrents, however, is that joint military drills can do nothing to erode them. If it will take a week to militarily defeat North Korea, that damage will be inflicted before the end of the week. That retaliation will be launched. War games, no matter how sophisticated, can do nothing to diminish the opening salvos of a war.

But let’s consider a couple of things that war games can do.

First, joint military drills humiliate North Korea. If there’s any lesson that a self-assured and confident man like President John F. Kennedy left us in the Cuban missile crisis, it’s to avoid kicking an opponent while he’s down, to leave him with a face-saving off-ramp, to allow him to salvage some pride. Imagine if some hypothetical military adversary of the United States—which had leveled fully 80 percent of American cities a few decades earlier and which now maintained a vastly superior military capability—flew hundreds of warplanes and sailed dozens of warships and test-fired countless weapons just a few dozen miles off the coast of San Diego or Boston or Miami. Wouldn’t that be humiliating and degrading and emasculating—especially for thin-skinned leaders like the ones currently in charge in both Pyongyang and Washington?

Second, and more importantly, North Korea cannot know that war games aren’t in reality preparations for war. And that could lead to a repetition of one of most terrifying and unknown episodes of the Cold War—the Able Archer crisis of November 1983.

Relations between Moscow and Washington at the time were strained, to say the least. President Reagan that March had publicly declared the Soviet Union to be an “evil empire.” Then in September, the USSR shot down a wildly off-course civilian airliner that had strayed over Soviet airspace—killing all 269 aboard, including 69 Americans. Reagan defense cognoscenti Colin Gray and Keith Payne published an article in Foreign Policy magazine, called “Victory is Possible,” which maintained that the U.S. could fight and win a “protracted nuclear war.”

So it should come as little surprise that when the “Able Archer” NATO military exercises commenced on Nov. 7, 1983—simulating not just war with the USSR but nuclear war—Soviet leaders frantically tried to ascertain whether the massive military movements were, in fact, not an exercise, but preparations for launching a full-scale invasion and a nuclear first strike upon the Soviet Union. During that time Soviet officers moved their nuclear weapons from storage sites to delivery units, and placed the ICBM force on “raised combat alert.” Although the full story of the deliberations inside the Kremlin may never completely be known, it seems far from impossible to suppose that during those 72 perilous hours, the Soviet Politburo of Yuri Andropov seriously considered ordering a nuclear first strike upon the United States.

Which, in all likelihood, also would have been the last nuclear first strike by anyone.

It will be a long road ahead to achieve an enduring peace in Korea. The United States must acknowledge that North Korea has a right to protect its own national security—and that, in the face of external threats, nuclear weapons are its only tool to deter an incalculably more powerful adversary. Any talks between Trump and Kim must be directed, most fundamentally, at eliminating those threats in exchange for eliminating those weapons. Such a grand deal ideally would be expressed in the form of a peace treaty to formally end the Korean War. This agreement would renounce any future “regime change” (much as we all might loathe what that regime does to its own people), provide genuine and irreversible security guarantees to Pyongyang, and chart a course toward the eventual goal of a single, unified Korea. After all, said Albert Einstein, “the real cause of all international conflicts is the existence of separate competing sovereign nations.”

But the first step down that long road, one that is simultaneously the most urgent and the most important, is to put an end to war games that simulate war with North Korea. Because one of these years, much like during Able Archer, North Korea might decide that those war games are no games.

What if Mike Pompeo, confirmed as the new secretary of state, makes more public utterances like the one he made at the Aspen Security Forum last year, when he said: “The thing that is most dangerous … is the character who holds the control. … The North Korean people I’m sure are lovely people and would love to see him go.” What if John Bolton makes “the legal case for striking North Korea first” not just in the pages of The Wall Street Journal, but as the new White House national security adviser? What if the summit between President Trump and Chairman Kim doesn’t happen, or flops, or devolves into bragging about the size of their buttons? What better way to commence a military assault, North Korean defense planners might say to each other, than to array an armada of military assets just off the coast of North Korea—yet claim that those forces are just engaging in military exercises?

Someday, North Korea might conclude that the U.S. and South Korea are not just practicing for a future war with the north, but are preparing to launch an immediate attack—perhaps even a nuclear attack. If that conclusion does indeed come home to roost in Pyongyang, what will decision-makers in North Korea do? What would Yuri Andropov do? What would you do, if you were Kim Jong Un?

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.