RIP, Printed Village Voice

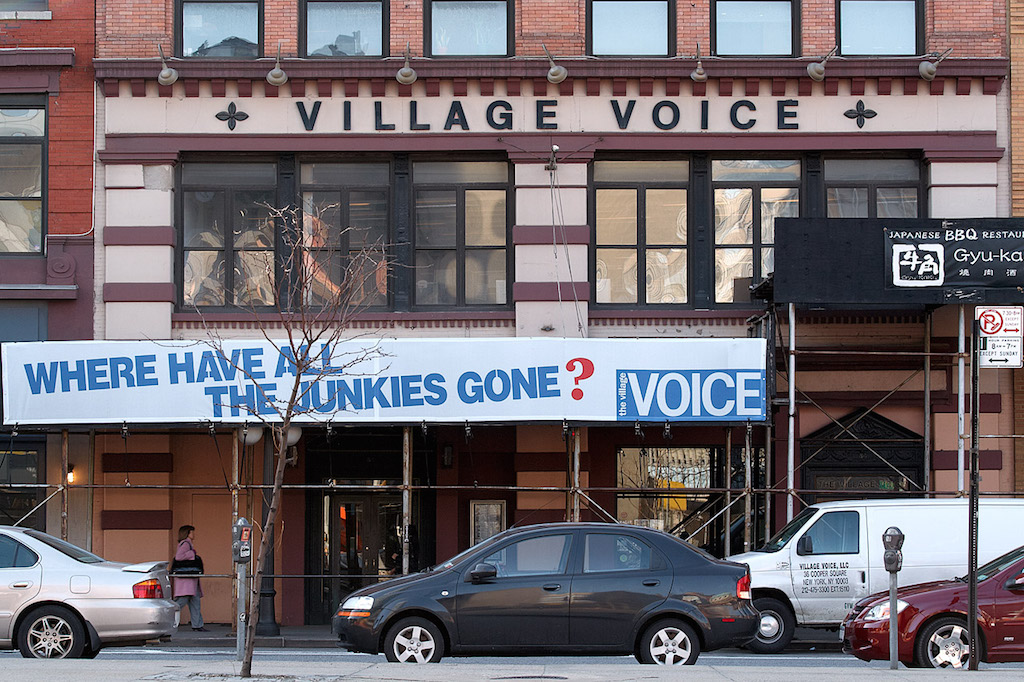

A former staff writer at the alternative newsweekly reminisces about the paper’s golden age in the 1980s. The former home of The Village Voice at 36 Cooper Square in New York City. (Herder3 / Wikimedia)

The former home of The Village Voice at 36 Cooper Square in New York City. (Herder3 / Wikimedia)

Wednesdays, the day the paper came out, were the best.

From our apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn, I’d take the 2 or 3 to Nevins, then switch to the 4. If the trains were running smoothly, it would be maybe a half-hour trip, 45 minutes at most, to Union Square and the short block to 13th and Broadway. If I had time, I’d walk one more block down and duck into Forbidden Planet, the best sci-fi and fantasy shop in the city, or to the Strand, which back then was loosely organized by genre, no cataloguing or real alphabetization, but it lived up to its boast of “Eight miles of books.” (Taking music editor Robert Christgau’s advice, I quickly learned to read—usually standing—on the subways and managed to get through five or six extra books a month.)

When you got to the Voice office and emptied your mailbox, it was like Christmas morning. In addition to the delightful hate mail, there were often complimentary letters. In the room in our apartment I used as an office, I plastered the wall with notes from George Plimpton, Norman Mailer, Wilfrid Sheed, Frederick Exley, and, my favorite, George Carlin. (I had quoted from his “Indian Sergeant” routine and, much to my dismay, my editor inserted a line suggesting the routine wasn’t funny. Carlin responded in mock horror: “Allen—The Village Voice hasn’t mentioned me in years, and now you say I’m not funny?” I wrote back to George, and we became pen pals.)

There were also books and records and invitations to book parties, movie screenings and promotional sports events. At one of these—either a meeting for the World Boxing Council or the World Boxing Association, I can’t remember which—I arrived an hour early, sat down to read and, after about half an hour, was startled to see the most famous man in the world emerge with his entourage from the elevator.

Muhammad Ali walked straight over to me and asked, “Wanna see a magic trick?” Of course, I did. He picked up a packet of sugar from the coffee-and-bagels table and instructed me to rip it open and pour it into his clasped hand. He then rubbed his hands together, pronounced some kind of magic gibberish and said, “Viola!” as he waved his hand. The sugar had disappeared—not a granule to be seen. Next to the day I was married and the day my daughter was born, it was the best day of my life.

There was always something going on, often a party at some new club that seemed like the ones Bill Hader’s Stefon talked about on “Saturday Night Live.” At one of them, the waiters and bartenders posed as gilded statues who came to life when you reached for a drink. There were Christmas parties at the Limelight, the old converted church on Sixth Avenue. I remember David Johansen as Buster Poindexter performing at the party two years in a row.

Like most Voice writers, I also received invitations from The New York Times, Esquire, New York magazine and others to write for them. As late as the early 1990s, if you couldn’t make an actual career out of writing for the Voice, it often served as the door to a career. In 1994 I got a letter from Lee Lescaze at The Wall Street Journal. Through him I began an association with the paper that lasted 23 years.

The Voice office often seemed like a four-ring circus with no ringmaster. There was so much noise, turmoil and confusion that you wondered how the next edition would close by Monday night, but it always did.

Once, I shot Nerf-ball baskets with the son of Sylvia Plachy; she was one of the definitive photographers in New York journalism, along with Fred McDarrah.

After actor Adrien Brody won an Oscar in 2003, I found out that the kid I had played with was him.

One afternoon, activity at the Voice screeched to a halt, and everyone ran from their cubicles to the center office to hear Mark Stamaty, the great cartoonist, do his impression of Elvis Presley reading Charles Dickens.

Another day, out of the blue, Zippy the Chimp skateboarded down the center aisle to deliver an invitation to a movie premiere. It was the kind of moment that makes me wish cellphones had been invented 20 years earlier.

On Thursday evenings in the spring, summer and fall, the office of America’s greatest weekly paper resembled a softball clinic for nerds as Jesus Diaz, who worked in graphics and layout and later became the systems manager, turned into Billy Martin and herded the Voice Veggies up to Central Park, where we won the New York Publishing League pennant twice. My most vivid memory of my softball career was listening to author Paul Berman standing on our sideline screaming, “Fuck da Nation!” as loud as he could. We did, too. (I never found out what they had done to anger him.)

The office always seemed to be in a state of exhilarating turmoil. Much of the turmoil centered around Stanley Crouch. More than any other writer, Stanley, to me, typified The Village Voice. He was both a progressive and a contrarian, the only black writer I can remember who had the cojones to take on Spike Lee. Stanley hated most rock and rap in the 1980s. I remember shouting coming from Bob Christgau’s cubicle during an edit when he tried to talk Stanley out of a potentially inflammatory line in one of his reviews. The more rational Bob got, the more irrational Stanley got—but in the end, they compromised.

As the guy says in “Blazing Saddles,” “Nietzsche said, ‘Out of chaos comes order.’ ” This kinetic energy produced remarkable investigative and cultural journalism. Week after week, the Voice lived up to its motto: “Expect the Unexpected.”

That’s the way it was at the Voice. It was a writer’s paper, but you listened to your editor—who was almost always a writer, too—and worked things out because he or she read your work carefully and respected what you had done.

Anyway, everyone respected Stanley, so they tolerated his high jinks, which included keeping a jet-black, loaded water gun in his desk that even up close looked like a real Colt .45 semiautomatic. When Mike Caruso, one of the younger editors, first started, Stanley would bait him by squirting water on the back of his head, making remarks like, “Ca-roo-so, that’s Eye-taleean, right? You with the Maa-fia?” Mike took it like a good sport. He was one of the better editors in the late 1980s and, after bouncing around several magazines, settled in at the Smithsonian.

The running joke about the Voice, no matter who you talked to, was that it was a better paper before you got there, going all the way back to 1955, when Norman Mailer, Dan Wolf and Ed Fancher started it. I can attest to how good the Voice was in the late 1970s, because I read it regularly in the basement of the University of Alabama library, where I worked my way through school by repairing and rebinding books. It explained New York to readers in much of America and much of America to readers in New York.

I’ve worked at The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, but have never seen anything comparable to the collection of talent embodied in the Voice editors and writers in the early 1980s. In addition to Stanley Crouch and Mike Caruso, they were, in no particular order:

Ross Wetzsteon

He was the best editor I have ever worked with anywhere. When Ross died in 1998, Michael Feingold said, “Soft-spoken and gentle in manner, he was a tower of quiet strength at the center of this paper.”

Ross was also a visionary theater critic. In the 1960s, he helped turn the Obies, the Voice awards for Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway theater, into a major event, and more than anyone else, he discovered and promoted Sam Shepard’s career both as a playwright and director.

One of the best critical essays ever written on Shepard was Ross’ introduction to “Fool for Love and Other Plays.”

Ross gave me my first assignment, in 1982, beginning my association with the Voice, which has lasted 35 years and more than 600 features, reviews and columns. His book, “Republic of Dreams: Greenwich Village: The American Bohemia, 1910-1960” was published posthumously in 2002. He loved baseball and was the first editor to offer Bill James a regular column (“Ask Bill James”).

Geoff Stokes

He was a staff writer for the Voice for 17 years and, like Ross, was a pillar of strength as an editor and adviser. He wrote the “Press Clips” column for the Voice and was the best press critic the city had seen since A.J. Liebling. Like so many writers at the Voice, he wrote on just about every subject, from Irish literature to politics (he came to journalism after working for years for the Democratic Party under Mayor John Lindsay) to baseball to food. (He wrote the acclaimed column “Waiting for Dessert” under the name of Vladimir Estragon.)

His book, “Pinstripe Pandemonium,” on the Yankees in the George Steinbrenner-Billy Martin era, was praised by Bill James as a classic and is still available on Amazon. Geoff moved his family to New Hampshire in 1992 and died three years later, after a stint as a columnist for The Boston Globe.

Robert Christgau (or “X-gau,” as he would sign his letters)

He was the self-proclaimed dean of American rock critics, and I never heard anyone dispute that claim, because, as Sean Connery says to Kevin Costner in “The Untouchables” when Costner says he is a Treasury agent, “Who would claim to be that who was not?” Bob listened to music like it was his duty and knew everything there was to know about American popular music of any kind.

At least once a week, he’d stop you and say, “Listen to this,” as he put earphones on your head. His “Consumer Guide” to new releases was often the first thing people turned to when they grabbed the new issue, much like Pauline Kael’s film reviews were the first thing you opened The New Yorker to. (I’m proud to say I once got the two of them together at lunch for an outstanding gabfest.) With the annual Pazz & Jop poll—the title a spoof on Playboy’s Jazz & Pop poll—Christgau brought hundreds of music writers all over the country together and did more to stimulate regional music than anyone else. (In 2014, the Voice reprinted his five favorite essays.)

And Christgau’s still at it. He recently wrote that Randy Newman’s new album is a contender for album of the year.

Kit Rachlis

Rachlis was managing editor from 1984 to 1988 and the best I ever knew at that level. He started out as a rock critic for Rolling Stone. His essay on Neil Young was included in Greil Marcus’ “Stranded: Rock and Roll for a Desert Island.” Like David Edelstein, he went from the Boston Phoenix to the Voice or, as I used to kid him, “from Triple-A to the majors.” He is currently a senior editor at California Sunday Magazine, a monthly insert for the Los Angeles Times and San Francisco Chronicle.

M. Mark

I never did learn her first name. For 15 years, she edited the Voice Literary Supplement, the best literary magazine in New York. She gave me my start as a book critic. She is currently an adjunct professor of English at Vassar and will still take time to talk about literature, especially if the author is Irish.

Enrique Fernandez

He was New York’s window on all things Hispanic, particularly Cuban. His obit of Cuban singer Tito Puente is a classic, and you can still read him on his website (see his tribute to the late Ellen Willis, posted on Oct. 29).

Wayne Barrett

One of the best investigative reporters of our time and the first writer to expose Donald Trump—you can still get his 1992 book, “Trump: The Deals and the Downfall.” He never let up and wrote a great piece on Trump and Rudy Guiliani for the New York Daily News last fall, titled “Donald Trump and Rudy Guiliani: Peas in a Pod.”

Also see one of his last pieces, “How Donald Trump Managed to Turn Triumph into Disaster,” which ran in the Voice a few months before Barrett’s death earlier this year.

Nat Henthoff

I once had a falling out, in print, with Nat on the subject of abortion (he was contra). He shrugged it off and always found a reason to take me aside and talk to me about some classic jazz artist. No more eloquent defender of free speech ever lived—find his 1992 book, “Free Speech for Me—But Not For Thee: How the American Left and Right Relentlessly Censor Each Other.” More relevant now than ever.

When Nat died in January, the Voice reprinted a piece I wrote in 2008 when he retired. The title says it all: “50 Years of Pissing People Off.”

Michael Feingold

The wittiest, most acerbic and best theater critic writing in New York or anywhere for more than two decades. Here’s his beautiful obit for Sam Shepard, “The Punk Rock Cowboy Who Never Stopped Searching.”

Leslie Savan

A whip-smart purveyor of the media and advertising scene whose column ran in the Voice for 13 years, she was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for criticism three times. In 2015, when the Voice was sold to current owner Peter Barbey, she told The New York Times, “The Voice was my best voice as a writer. I never found that voice again.” Not true: She’s doing just fine at The Nation.

Dan Bischoff

The official byline for Dan was “chief political and investigative editor,” but he was a pretty good editor for just about any subject. And if you needed steering in the right direction on whatever you were working on, you only had to seek him out. He is an excellent writer, too, and after he left the Voice became art critic for the Newark Star-Ledger.

Andrew Sarris

In all the years Andrew Sarris wrote about film for the Voice, I never met him. (I finally caught up with him when we were both writing for the New York Observer—in the pre-Jared Kushner days.) I always thought his auteur theory was a crock, but he was a great critic, and I enjoyed reading him in spite of his theory, not because of it.

David Edelstein

In all the years I’ve read David Edelstein, I can’t say that I ever detected an ounce of film theory. He, and not the Voice’s J. Hoberman, was the critic most open to new filmmakers and new sensibilities. At New York Magazine/Vulture, Edelstein is still the best.

Greil Marcus

I don’t know if Greil was ever a staff writer for the Voice, but his “Real Life Top Ten” was one of the first things many Voice readers flipped to. His book, “Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock and Roll Music,” with chapters on Elvis (“The Presleyiad”), Robert Johnson and The Band, published in 1975, had an enormous impact on a generation of upcoming cultural writers. He has written numerous important reviews since.

I owe him much. In 1988, he sent me a postcard sharply disagreeing with comments I made on the Oakland A’s. It was the kind of response that, yea or nay, assures you that you’re being read.

Here’s my interview with him for his book, “The History of Rock’n’Roll in Ten Songs.”

Jack Newfield

I didn’t know Jack well, and by the time he left the Voice in 1988 to join the New York Daily News—after a quarter century of writing for the Voice—he had become, to be brutally honest, a watered-down version of his early, fiery self. He already had credentials before he came to the Voice. In 1963, he spent two days in a Mississippi jail with Michael Schwerner, who was later murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. But, damn, in the 1960s and 1970s, he could be fiery, and he had the courage of his convictions.

One of my favorite quotes from him, about muckraking journalism: “Create a constituency for reform and don’t stop until you have made some progress or positive results.” His best book, on Rudy Giuliani, “The Full Rudy: The Man, The Myth, The Mania,” won the American Book Award in 2002, only two years before his death.

Oh, yes, he also liked boxing. He was the first one I remember to write about Mike Tyson.

James Wolcott

I don’t think I saw Wolcott at the Voice office more than twice. (He didn’t get along with several of the editors, culturally or politically.) For years he was the wittiest and most acerbic television critic in the country, sort of what Clive James was to The Guardian in Britain. (My favorite Wolcott pieces were his fake episodes for the “Brideshead Revisited” series.) The Voice was so slow to keep up in the digital age that very little of that work is available except for what he included in his 2013 book, “Critical Mass: Four Decades of Essays, Reviews, Hand Grenades, and Hurrahs.”

Joe Del Priore

Unless you read the Voice in the mid-to-late 1980s, you probably don’t know his name, and, sadly, I can’t include any links to his stuff because none of it is online. But to me, he represented, more than any other writer, what the Village Voice was about. He was strictly blue-collar, a mailman from Weehawken, N.J., who mailed some pieces to Ross Wetzsteon and Geoff Stokes, mostly on sports, that were so funny they were published almost without edit. I’m told he was a pain in the ass to edit, but he had one of the most spontaneous caustic wits I’ve ever experienced. During a particularly tough edit with Doug Simmons (who succeeded Christgau as music editor), he shouted, “When I want your opinion, I’ll ask Robert Christgau for it.”

In 2013, David Edelstein, writing an obit for the closing of his first alternative paper, the Boston Phoenix, said that “alternative journalism doesn’t mean what it did back then. Most journalism—almost everything on the Internet—is ‘alternative.’ We won, and the Phoenix, I guess, finally lost.”

I hope the Voice can continue and find its new voice as an online-only publication. But if I had to pick one reason why it failed to continue as a print paper, I’d lean toward what Edelstein wrote. The Voice and other weekly papers around the country (including the Chicago Reader, which I wrote for briefly before coming to New York) helped make all journalism, and particularly internet journalism, into alternative journalism.

There’s one major difference between online and print journalism. When I started writing for Salon in 2000, the site’s founder, David Talbot, told me, “We’re hoping we can establish the same kind of atmosphere at Salon that you had at The Village Voice.” But you can’t have the exhilarating, creative atmosphere of an office when everyone’s writing from their home without the benefit of exchanging ideas in person with other people. You can’t have The Village Voice without Zippy the Chimp.

Last one out, turn off the lights.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.