A Conversation With Greil Marcus

Allen Barra sits down with cultural critic Greil Marcus to discuss “Real Life Rock,” a book compilation of Marcus’ “Real Life Rock Top Ten” columns written between 1986 and 2014, and “Three Songs, Three Singers, Three Nations,” his collection of William E. Massey Sr. Lectures in History of American Civilization 2013 at Harvard University. Yale University Press

Yale University Press

To see long excerpts from “Real Life Rock” at Google Books, click here.

Allen Barra: First of all, let me thank you for bringing all these “Real Life Top 10” columns together. Those of us who clipped and saved them over the years have always had a real mess on our hands trying to preserve them.

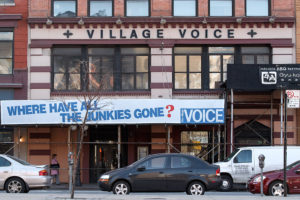

Sometimes your items remind me of the capsule reviews that Pauline Kael wrote for The New Yorker; others are a little like Robert Christgau’s Consumer Guide in The Village Voice. But I’ve never read anyone who covers such a range of topics the way you do. Are there any models for the idea of “Real Life Top Ten”?

Greil Marcus: No, and I certainly never imagined the column would continue to renew itself, or anyway me, in so many different publications, and still be what it might yet become today. Bob’s column was all records — this was never going to be that. In terms of compression, passion, impatience, Pauline’s capsules — what she collected in “5001 Nights at the Movies,” so much of it drawn from her program notes for the Cinema-Guild theaters in Berkeley from the ’50s and ’60s, as were her New Yorker capsules — I could take that as a mountain to climb in retrospect, but I wasn’t thinking of that at the time, which is to say over a very long time.

AB: You talk a little in your introduction about the history of “Real Life” and how it’s evolved over the years. I mean, there doesn’t seem to be anything else like it. I can’t think of any — what’s a good phrase here? — cultural critics who wrote about as many things as you did (and do) and tied them all together with a single sensibility. …

GM: As I mention in the introduction, in the early 1980s I wrote a music column for New West called “Real Life Rock” — a conventional essay column. At the end there was a little list called “Real Life Rock Top 10,” which would include records, TV appearances, ads, shows, books, even a guitar solo. After the column ended, Doug Simmons, then the music editor of The Village Voice, suggested I turn the un-annotated list into a real column, at 700 words a month. Right off it was clear that bringing as much into it as possible — absurd news items, maybe with my own title but no commentary, advertisements deconstructed into tiny critical theory essays, clothes someone wore, books, movies, TV shows, overheard comments, and soon enough contributions from readers, some assigned, mostly not — was the way to make it irresistibly fun to compose and I hoped to read. The first column started with a track from a Columbia new-artists compilation album — from a band that I never wrote about again — and included an item on a tiny fire-breathing Godzilla toy I still have. As it went on it took in museums, galleries, political speeches, elections and world events. I was stunned, devastated, broken by the massacres in Tiananmen Square, I had a column due, and I wrote “Zero” and sent in a fragment of a wire service report — I don’t remember if I tore it or the Voice art director did. Really, that column was the art director’s more than mine, which is why it’s the only column in the book reproduced as it originally ran.

So I’m not answering your question. I had the freedom to do what made sense and I hope I was able to take advantage of it.

AB: A friend of mine — who lives in Berkeley, by the way — says that reading your “Real Life” columns is like flipping across a whole bunch of really cool radio stations from oldies channels to college stations to talk shows where “you hear someone say something that grabs your attention even when you’re not entirely sure what they’re talking about. People are talking about really cool stuff but you don’t always know what that is because you came in midway but you’re hooked.” I don’t know exactly why I’m telling you this, but I thought you’d like to hear it. Do you have any response to that?

GM: Not that I ever put it into those words, but that fulfills all my hopes for the column.

AB: Sometimes I feel I don’t quite get what you’re aiming at, but I know it’s something I want to understand better. Help me a little with this about Lana Del Rey’s “Ultraviolence”: “Lana Del Rey knows how to wait out a song, and this album may know how to wait out its time.”

GM: What makes the column work — its necessity — is compression and metaphor. How much can you say in the fewest words? Are the 700 or 1,000 word columns in the Voice or Artforum or City Pages, in print publications with a strict word limit, better than the open-ended columns from Salon or the Believer? Here I was trying to capture both her sensibility regarding a song and her sensibility, or instinct, about pop music as such. So what I meant was this: As she writes and sings, she can wait for a song to reveal itself. That’s what her music sounds like: There’s almost always more there at the end of a song than at the beginning. And that while this music might seem light — all surface, all effects, all marketing, all persona, are certain to evaporate — it might be close to permanent, and make as much sense, communicate as fully, and retain or even deepen its suggestive power, far into the future.AB: And this on the great Argentine writer Julio Cortázar: “Like no one else I’ve read… [he] gets to the oddity of the fraternity that comes together when one is listening to and feeling at one with the dead, who on records are more physically present than in any other medium: on the page, on the screen, even in a personal memory of a night when you were there to see the singer, alive.”

I love that, but I’m not completely sure why. Could you nudge me in the direction of understanding it better?

GM: [Cortázar’s] novel is about a bunch of expatriate-record-collector/jazz-and-blues-fanatics in Paris in the ’50s talking about Bessie Smith and Bix Beiderbecke. That [these musicians are] dead is a big part of why these people are drawn to them — they can’t say any more. What they did say suggests infinite new worlds, but you can’t ask them what they meant, and there will never be any more clues. So you listen, together, ever more intently, and you ask each other what it means, and you’re more aware, then, of the absence of the people you’re listening to than in any other aesthetic circumstance, even if you’re thinking about someone dead who you saw perform in the flesh, as none of these people ever came within thousands of miles of the people they’re talking about. Which is to say a constructed memory can be more powerful than a direct memory.

AB: In a 2013 column you devoted an unusually long chunk of space to Philip Kaufman’s HBO film “Hemingway & Gellhorn.” I loved this piece, so I’m going to quote a long passage:

“The reviews were dismissive at best — as they were for ‘The Right Stuff,’ nicely setting people up to be surprised at how tough it was. This is the same. What were reviewers watching, and what were they thinking, what sense of discomfort or ingrained disdain was behind the refusal to see what’s on the screen? As the war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, Nicole Kidman has never been harder to look away from, and her looks — fire in her cheekbones, intelligence in her eyes — are part of why it’s her most convincing part and performance since ‘Malice.’

“This is historical drama, taking the protagonists from the Spanish Civil War to the Japanese invasion of China to the Soviet assault on Finland — the 1930s before the world war had come together — when it was one fireball after another — and the most startling element in it is the way Kaufman drops his characters straight into historical documentary footage. … The technique is a miracle here. Most of the time I couldn’t tell what, when the actors were present, was historical footage and what wasn’t, when a scene was unfolding or was constructed, and quickly didn’t care. Something shocking and revelatory was going on.”

I picked this passage about this particular movie because it’s great criticism and because your judgment is absolutely correct — “What were reviewers watching, what were they thinking, what sense of discomfort or ingrained disdain is behind their refusal to see what’s on the screen?” I’m going to disguise that a bit and use it in something I write some day.

Why is it that so many were so dismissive of this great film?

GM: We’d have to ask them, and they wouldn’t tell us, and they’d lie. Some of it might have to do with Kaufman working in San Francisco, and not schmoozing enough, not seeming legitimately Hollywood — far more important to most critics than they would ever let on — real independents threaten the system they rely on, which is to say they threaten them. People might genuinely not like Kaufman’s intellectual ambitions, which can easily be dismissed as pretentions — who was he, really, to take on Kundera, the Marquis de Sade, Hemingway, even Tom Wolfe? They might think he bites off more than he can chew. And they might be offended by precisely the historical confusions — inserting actors into documentary historical footage, some of it, as with the Republican soldier being shot on the hillside or the baby in the Shanghai rail station, absolutely canonical — that I find so thrilling.

AB: And why is it that this piece of writing, long after the returns were in, can mean more to a reader in retrospect than when the reviews came out?

GM: Not to be obnoxious, but it’s not just trying to say good or bad, it’s actually trying to raise an interesting question. But really, that’s for you to answer, not me.

AB: I keep looking for passages in “Real Life Rock” that would explain your work to someone who had never read these columns. I don’t know if this does it, but in Feb. 2010 you wrote up Bob Dylan and Dion, United Palace Theater, New York, Nov. 17, 2009. Now I’ve got to tell you, I was away at the time — there’s no show I would have wanted to see more than that one. You wrote:

“Dion stole the show, he opened with Buddy Holly’s ‘Rave On’ — and that had to remind both Dylan and the crowd of the night in early 1959, just days before Holly died, when a seventeen-year old Robert Zimmerman sat in the Duluth National Guard Armory, Holly himself sang ‘Rave On,’ and Dion was an opening act at that show. … Now [Dion] was seventy and his voice grew, opened, gained in suppleness and reach with every song. … One by one, he put the oldies behind him, so that it all came to a head with ‘King of the New York Streets’ from 1989.

It’s a gorgeous, panoramic song: a strutting brag that in the end turns back on itself. … After the song has gone on and on, you can’t bear the idea that it’s going to end.”

Then: “Dion’s wails were as fierce as ever, but never so full of wide-open spaces, the voice itself an undiscovered country, and it was impossible to imagine that he had ever sung better.”

This may not have much to do with what you wrote, but if I don’t say it now I’ll probably never get the chance. In the early 1980s I wrote a long appreciation of Dion for a long-defunct magazine, and somehow, God knows how, you saw it and wrote me a wonderfully appreciative postcard. That kind of made my year.

But back to the subject. How in hell do you write something like that about Dion and that song? Could you possibly have taken notes the night of the concert? Did you write it up the moment you got back that night?

I guess what I’m asking is how you keep a moment like that fresh in your mind until you can get it down?GM: I scribbled notes, but really, all those thoughts were brought on by the performance, and all I had to do was think about it again for it all to come back. I don’t remember if I made some clearer notes when I got home, but I wouldn’t have written it up until days or a week later.

AB: If I can jump to your book, “Three Songs, Three Singers, and Three Nations,” which was developed out of your 2013 Massey Lectures at Harvard. But pull this together for me. Why did you zero in on these three songs — Bob Dylan’s “Ballad of Hollis Brown,” “Last Kind Words Blues” by Geeshie Wiley and “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground” by Bascom Lamar Lunsford?

GM: I’ve been fascinated for years by what I’ve taken to calling the commonplace song — other names for it are the folk-lyric song, or just folk song — songs that seem to have no author or authors, songs whose elements can’t be fixed, or traced to any specific person, time or place, that seem to have come together from a vast and floating pool of musical and verbal phrases — verses, couplets, single line, single images, snatched or melody, riffs full or partial, place names that signify (“Played cards in England, played cards in Spain”) — but function solely to give authority to the singer, so he or she can make you believe the story being told, and are meant to have no real, as opposed to narrative, biographical meaning at all. When a singer says, as so many do, “I’ve been all around the world,” he (for this line it’s always a he) means, “I know the score,” but it sounds and feels so much bigger than that.

Where did that line originate? Does it matter? It’s part of a special shared language that anyone can use for their own purposes, to tell their own story, to describe how life and the world looks to them, while not using a single so-called original element.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground” really is what I’ve just described. Nothing in it can be attributed. When he first heard it, about 1900, he heard what he would record a quarter century later — he didn’t, as far as anyone knows, alter it, though he knew of versions traveling under different names with different elements present. So that’s an absolute folk-lyric or commonplace song.

Geeshie Wiley’s “Last Kind Words Blues,” from 1930, has enchanted me — and many other people — since I first heard it in Terry Zwigoff’s movie “Crumb.” I was out of the theater and to the record store looking for a soundtrack album just like that. Parts of the song are completely, inevitably traditional — “My mama told me” — you have to follow that with “just before she died,” and Wiley does. There are many commonplace or shared or folk-lyric phrases and images — but many of them, maybe all of them, are just slightly skewed, with Wiley not saying what the singer of these things is supposed to say, or seeming not to. The music is recognizable as blues but also not.

The self-presentation of the singer — in a blues song, you describe what happened to you, you present yourself as having experienced everything that happens in the song, to have thought every thought that’s expressed — is unstable [in “Last Kind Words Blues”]: You never know who’s speaking, if it’s the singer, various characters in the song, or if, in the epistemology of the song, the singer even exists. And there are verses in the song that never appeared in any song before this one and never migrated to another after it, but which rest on the traditional elements, both to, perhaps, protect the singer from the dangerous things she’s saying, giving voice to thoughts no one has ever had before in words no one has ever used, or to give her the authority to both embrace tradition and cut it into pieces: to speak publicly in her own voice, but hiding behind a pseudonym, a nickname, as if, really, she, “Geeshie Wiley,” didn’t exist, or didn’t have to, as if she was, as it happened, someone else.

I’ve written about these two songs, taught them and lectured on them, for years, and with the three-lecture Massey series, here was a chance to get as far into them as I could, leaving nothing out, raising every possibility of what these songs were and what languages they spoke.

With the book version I didn’t have a time limit, but the music that I could play in a lecture and then discuss now had to be put on the page, had to play on the page. But then I wanted another kind of commonplace song: one that seemed to be what it wasn’t, one that communicated as if it were the product of some common dream, but was brought into the world in the most defined way. And Bob Dylan’s “Ballad of Hollis Brown” just jumped out. I’d never written about it. I’d thought a bit about why it was so powerful, and so unhitched from time and place — there’s one specific reference in it, “North Dakota,” which makes you think this story of a destitute farmer who kills his family and himself was based on a news story contemporaneous with when the song was made (1963-64), which it wasn’t.

But it also sounds as if it speaks the language of the Great Depression, of the Dust Bowl, and many people have assumed it’s a Depression folk song, and fans’ YouTube videos place it right there. But it could have come out of the Great Depression of the 1890s — and for that matter, for a small farm the Great Depression could always come next year. Dylan based the music on the traditional ballad “Pretty Polly,” but the song is entirely original — in a legal sense. Dylan wrote it, he copyrighted it. But it speaks a commonplace language. There are details of particular drama or intensity that, you can think, only Dylan could have come up with — but that might not be true, and as he wrote and at first tried out the song (“A true story,” he’d say), he might have felt he was writing a song that in the most important sense was already present, or preordained.

Those three songs seemed to catch the borders of a country comprised of one great, shared, only partially written song.

AB: In the second of those essays, you write one of my all-time favorite Greil Marcus passages: “When art reaches a certain pitch, the artist disappears into her song, and we don’t care who she was, where she went, what she meant. We care what the song says.”

I’ve got to work one more question in. I found that in the last, let’s say, 15 years, pop music has exploded into so many different categories and sects that it’s impossible for me to get a grip on it.

Are there any young writers on the subject of pop music that people like me should know about? Anyone that you read who keys readers in to something good we might have missed?

GM: That I’ll have to think about. But there are remarkable people saying things that haven’t been said before in Pitchfork Review.

Thanks for giving me the chance to say all this.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.