Why Putin Let Russia’s Richies Take a Bath

The collapse of the Cypriot banking system reveals much about the complex relationship among ordinary Russians, "offshore oligarchs" and a political system that depends on both.

The collapse of the Cypriot banking system reveals much about the complex relationship among ordinary Russians, “offshore oligarchs” and a political system that depends on both.

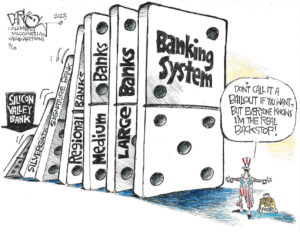

If anyone needed a reminder that Europe’s debt crisis is not over even though the European Central Bank is flooding the capital markets with cheap money, he or she would have to look only to Cyprus. The island’s banks virtually collapsed in March. The recession, the downgrading of the country’s investment rating and the Cypriot banks’ large losses on Greek bonds forced Cyprus to seek international help in order to avoid state bankruptcy.

The island negotiated with both the European Union and Russia. Cyprus is one of Russia’s largest foreign investors and Moscow had already granted the country a loan of 2.5 billion euro ($3.3 billion) in 2011. In spite of lucrative offers that included the rights to exploit natural gas off of Cyprus’ shores, the Russian government was not inclined to provide an additional loan. As a result, Cyprus had to accept the tough conditions of the EU troika in return for a 10 billion euro ($13 billion) bailout: tough cuts in state services and the factual liquidation of the two largest Cypriot banks.

Since Cyprus needs at least 27 billion euro ($35 billion), the government decided to raise some of the remaining money from owners of bank accounts on the island. Accounts with more than 100,000 euro ($130,000) in them will have to take a “haircut,” essentially a state seizure of assets of up to 80 percent. Aside from Cypriots, this measure mainly affects Russians. The Mediterranean island has for years served as the most important tax haven for wealthy Russians and the business community, and for that reason, foreign investment in Russia is as likely to originate in Cyprus as anywhere else. In 2011, alone, the island sent $13 billion to mother Russia, and a lot of that money was simply returning home.

Russians loved Cypriot bank accounts for their lax regulations and the ease of tax evasion. Mainly, though, Cyprus acted as a secure place for Russian capital because businessmen are afraid that their money is not safe in Russia itself. They understand that the fate of companies depends on their political favor. Furthermore, they do not trust Russian courts to settle legal conflicts independently of political influence, Tim Worstall explains in Forbes magazine. Russian businesses prefer countries with reliable legal systems, particularly the U.K. and Switzerland. As Cyprus continues to be under British legal jurisdiction, the island represented an obvious choice.

As it turns out, though, Cyprus was not as risk free as the Russian business community had hoped. The government’s decision to drain bank accounts is unprecedented in the European Union. The fact that it affected mostly Russian assets certainly made it easier to sell to the EU. Russian President Vladimir Putin criticized the European Union strongly after the Cyprus decision, talking about “expropriation of investors” and a “loss of confidence in the banking system of the eurozone.” He nonetheless could not hide a certain amount of satisfaction when he stated in a German television interview that “all of those damaged or intimidated, we hope, or at least many of them, will come to us and bring their money to our banks.”

The comment illustrates that Putin is somewhat torn in his assessment of the Cypriot crisis. On the one hand, Russian companies incurred significant losses. The newspaper Kommersant estimates them at 1.5 billion to 2 billion euro ($1.9 billion to $2.6 billion). In mid-April, the Russian stock market reacted negatively to news that the EU’s 10 billion euro bailout would most likely not suffice. Moreover, some commentators, among them Max Fisher in The Washington Post, think that Russia suffered a geopolitical defeat. He argues that Russia’s unwillingness to bail out Cyprus represented “a failed bid by Moscow to reassert some of its once-vast power in Europe and to stand up as an alternative to the European Union.” It’s not clear, however, that Russia would have been able to really influence decisions about the European financial crisis by bailing out Cyprus.

It is more likely that Russia would have endeavored on a very expensive and dangerous financial adventure by becoming more involved in Cyprus than it already is. It seems that Moscow is rather trying to minimize its losses, agreeing in early May to a renegotiation of its loan from 2011, accepting a longer duration and a lower interest rate — but nothing more.

One reason for this policy is that the Cyprus crisis is turning out to be less disastrous for the Russian economy than some had predicted. The Russian businesses that suffered the largest losses are small to midsize. The large investors, on the other hand, seem to have pulled most of their assets out of the country at the first sign of trouble earlier this year. For example, the Russian Commercial Bank VTB, which had assets of up to $1.8 billion in Cyprus, reports to be virtually unaffected. Wealthy Russians moved their money to other tax havens and also to the United States, buying, among other things, expensive real estate in New York City in recent months.

Another key to Russia’s hands-off approach is that Putin has in recent months repeatedly expressed his strong dislike of the Russian elite’s hefty foreign holdings. His reaction to the Cyprus crisis indicates that he considers it a lesson for those Russians who tried to hedge their assets. Rhetoric against “offshore oligarchs” who keep their money abroad instead of in Russia is popular in a country with great resentment toward the financially powerful. Even though some bloggers accuse Putin of having his own offshore accounts, he has tried to present himself as a fighter against widespread corruption among Russia’s leadership. A state bailout for oligarchs in Cyprus would have been a politically unwise move.

On the other hand, Putin could not have missed the fact that an upper echelon that can always safely leave its country without financial repercussions is not the best power base for a government that is confronted with mounting social and political tensions. In February, the Russian State Duma thus passed a law that bans officials from holding assets and bank accounts abroad. The government is hoping to repatriate as much as $1 trillion. In a “Direct Line” television appearance in late April, Putin said officials had to make a choice: “saving money abroad or serving the citizens of the Russian Federation in the high-ranking positions they have achieved through their service.”

The events in Cyprus might thus play into the hands of the Russian leadership, allowing it to advance its political agenda. Whether it will succeed in returning significant sums of money to Russia is, however, more than doubtful. This will most likely happen only once the underlying problems — that property is not safe from the grasp of judicial and political arbitrariness in Russia, and the widespread notion that the financial elite appropriated its money illegally in the 1990s — are addressed.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.