Why Neil Gorsuch Is a Dream Choice for Right-Wingers

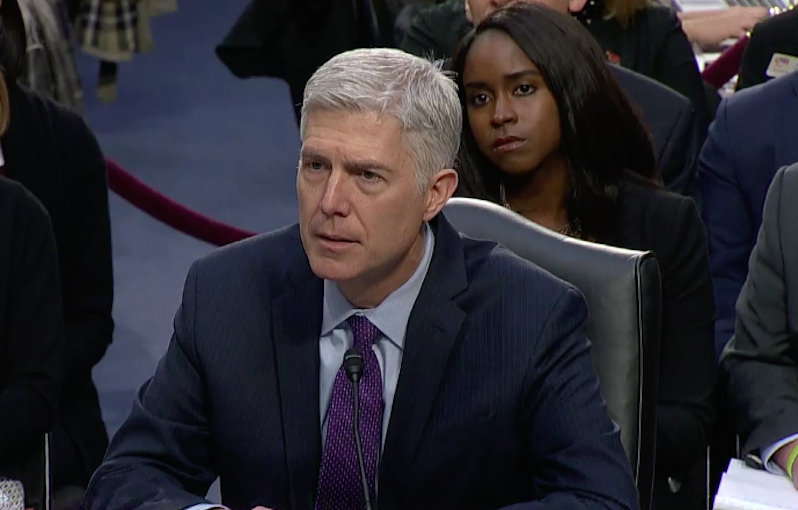

Born into the conservative movement, the Supreme Court nominee has been well trained in its ideological orthodoxy. Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch on the second day of his confirmation hearings. (Screen shot via NPR)

Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch on the second day of his confirmation hearings. (Screen shot via NPR)

By Jefferson Morley / AlterNet

Neil Gorsuch’s road to his confirmation hearings as Supreme Court justice began in boyhood. Before he was in his teens, he was handing out fliers in suburban Denver for his mother, a Republican attorney campaigning for the state legislature.

He came of age in the 1980s, teasing liberal classmates and teachers that he favored “Fascism Forever” while his mother served a controversy-filled 22 months as administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under President Ronald Reagan.

At Harvard Law School, Gorsuch joined the Federalist Society, the conservative legal group that has spawned hundreds of federal judges. As an aspiring corporate lawyer in Washington, he served as counsel and friend to billionaire Philip Anschutz, a leading funder of conservative causes and publications, who touted him for a federal judgeship.

And when President Trump was looking to solidify support from skeptical conservatives by pledging to appoint a right-wing judge to the Supreme Court, the Heritage Foundation put forward Gorsuch’s name.

At every stage of his life, Gorsuch has been nurtured by the organizational infrastructure of what was known as the New Right. Fighting a rear-guard action against the ascendant liberalism of the ’60s, the activists of the New Right built elite organizations with three goals. First, take control of the Republican Party away from pragmatists who had made their peace with the New Deal. Second, demonize and defeat Democrats who sought to protect and extend the social welfare state. And third, use the law to impose the conservative orthodoxy of corporate rule on American democracy.

Even the election of Donald Trump, the most ideologically unorthodox Republican president ever, did not disrupt their march to power. Gorsuch exemplifies what journalist Sidney Blumenthal called “The Rise of the Counter-Establishment.”

Elite Polish

So Gorsuch comes to the witness chair well-trained. He is, says law professor Zephyr Teachout, “polished to a fault. I mean, he really is the sort of dream elite candidate in that way.”

Personally affable, he has a knack for making friends with elite liberals who disagree with his politics but share his passion for the law and for debate. Neal Katyal, a senior Obama administration lawyer, endorsed him within days of his nomination.

Gorsuch comes across as thoughtful in his interpretation of the U.S. Constitution; he is an “originalist,” much like the justice he seeks to replace. Like the late Antonin Scalia, he places high value on what the original intent of the framers of the Constitution and its amendments intended.

Originalism isn’t necessarily reactionary. There are liberal “originalists” too. In making law about marriage equality and business regulation and civil rights, the liberal originalists look to the intent of the Constitution’s amenders—the Reconstruction Republicans after the Civil War; the women’s suffrage advocates and other Progressive Era-crusaders in the 1910s; and the civil rights reformers in the 1960s. Akhil Amar of Yale Law School, a leading liberal originalist, calls Gorsuch “honorable and admirable.”

But Gorsuch’s conservative training and elite polish have drained his jurisprudence of the ultimate humanity of the law—justice.

“I hate to break it to you, Democratic senators,” wrote Philadelphia Daily News columnist Will Bunch, “but Neil Gorsuch is not a nice guy, unless the bar for ‘nice’ has suddenly been lowered to smiling and slowing down to 15 mph while running over pedestrians.”

Corporate Politics

Bunch cites the telling story of Alphonse Maddin, a truck driver whose brakes froze in frigid weather. After shivering for hours waiting for a repair truck, he abandoned the trailer and drove to a gas station—a sane decision for which Maddin’s employer unceremoniously fired him. Two appeals judges on the 10th Circuit ordered Maddin rehired, while only Gorsuch sided with the corporation.

“It might be fair to ask whether TransAm’s decision was a wise or kind one,” Gorsuch wrote. “But it’s not our job to answer questions like that. Our only task is to decide whether the decision was an illegal one.”

That’s a reasonable question for a judge to ask, but Gorsuch’s reflexive answer betrayed the deficit of justice that so often informs his legal thinking. As Bunch writes, “It’s not a coincidence that in Judge Gorsuch’s America, the big corporation is right again and again and again.” Bunch continues:

Gorsuch has said in the past that he’d likely overturn the so-called Chevron doctrine—a 1984 court ruling that has given federal regulatory agencies the ability to better regulate pollution from power plants or crooked bankers. He’d make it harder to sue for stock fraud. The electrocuted mining worker? You’ll be shocked to learn that Gorsuch sided with the bosses on that one, too.

What Gorsuch’s New Right training taught him was to avoid the three pitfalls of an earlier generation of conservatives.

Conservatives in the 1960s found themselves marginalized and divided. The far right was dominated by the conspiracy theories of the John Birch Society, which depicted Dwight Eisenhower as a communist sympathizer and campaigned against fluoride in the water supply. They came across as fanatics.

The conservatives who opposed the civil rights movement were dominated by offshoots of the Ku Klux Klan like White Citizens’ Council. They came across as racist.

Big business conservatives were led by corporate executives willing to negotiate with labor unions and government regulators in return for stable profits. They came across as pragmatists.

The New Right abandoned the conspiracy theories in favor of legal theories of “originalism.” They jettisoned blatant racism in favor of “colorblind” justice, which is reliably blind to subtler strains of white supremacy. And they shunned pragmatic Republicans in favor of delegitimizing the welfare state. In the process, the Republican Party was transformed, over the course of a generation, from the small-government party to the anti-government party. Gorsuch is the product of that transformation.

What Democrats face in Gorsuch’s confirmation hearings is not just the duty to pass judgment on the man who would sit on the highest court of the land. They also face the obligation to pass judgment on the machine that put him there.

Jefferson Morley is AlterNet’s Washington correspondent. He is the author of JFK and CIA: The Secret Assassination Files (Kindle) and Snow-Storm in August: Washington City, Francis Scott Key, and the Forgotten Race Riot of 1835.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.