Where Gentrification Meets Joyful Resistance

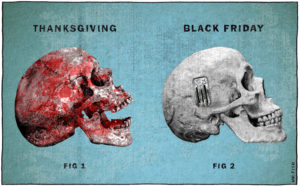

Lori Powers and the public art tradition in Los Angeles. A piece of Lori Powers' street art on display in Mar Vista. Photo: Paul Von Blum

A piece of Lori Powers' street art on display in Mar Vista. Photo: Paul Von Blum

Photo Essay

Where Gentrification Meets Joyful Resistance

Photo Essay

Where Gentrification Meets Joyful Resistance

For well over thirty years, I have lived in the westernmost part of Mar Vista, a Los Angeles neighborhood adjacent to Venice and Santa Monica. When I moved there from Venice, my desires were simple: to find additional space for a growing family and be relatively close to my work at UCLA. Mar Vista was a quiet place of mostly small single-family houses with longtime residents, many of whom knew each other and maintained friendly and helpful relationships with one another. It was, and generally remains, an appealing location.

But much has changed. It has become a place of increasing gentrification as older residents move away and pass on their property to children. The most disturbing phenomenon has been what many residents call the “mansionization” of Mar Vista, a reality found throughout much of the Greater Los Angeles area, but especially on the West Side of the city and its suburbs. The familiar pattern is characteristic of contemporary capitalism: Rapacious developers sweep in, demolish smaller homes and erect large box-like structures sold at the outrageous prices found throughout the inflated real estate market of coastal Southern California.

Most of these new residences are extremely unappealing luxury buildings; a few have attractive architectural designs. I know them well because I drive, walk and run through the neighborhood every day. Some of my new neighbors are pleasant and available for conversation. Many others are interested solely in holding the property long enough to “flip” it at a considerable profit, one of the most conspicuous forms of economic “development” in the region in recent years. Each time I see the sign “Notice of Demolition” or some variant, I think about the charming house about to be taken down on my street or nearby, and frown.

Lori Powers’ work is not directly political in the sense that the content of her work is more whimsical and charming. She does “want to change the world a little bit.”

I know that this is also a common reaction among many of the other longtime Mar Vista residents. Except for some anti-mansion signs and occasional graffiti, there is little opposition to the growing gentrification. Political opposition in the Los Angeles City Council seems fruitless and no genuine relief from this urban carcinogenic tendency appears likely. Los Angeles is mired in contentious politics and scandal, putting the transformation of Mar Vista and other neighborhoods on the proverbial back burner, where it is unlikely to make major inroads in the corridors of municipal political power.

Into this void, a street artist named Lori Powers has recently emerged with a public response in the forms of 22 whimsical public sculptures. Placed on telephone poles along two major East-West thoroughfares in the neighborhood, her imaginative works provide a wondrous visual experience to pedestrians, bike riders and drivers. My personal reaction is common. Each time I walk, run or drive on these two streets, I find myself smiling, because my personal reaction has broader significance. These public artworks cumulatively continue a long Los Angeles tradition of profound street art as a response to social issues. To be sure, gentrification in Mar Vista and much of the region may not rise to the level of continuing police misconduct and brutality against people of color and a multitude of other more egregious political, social and economic problems. Lori Powers’ work is not directly political in the sense that the content of her work is more whimsical and charming. She does “want to change the world a little bit.” Her artworks are socially meaningful in a truly remarkable way: They engage their audiences and often encourage them to reflect on broader social concerns. That fulfills one of the highest functions of socially conscious art.

For decades, graffiti writers have used walls and other public and private surfaces to express their deeply felt grievances. This was especially the case regarding the obvious racism in Los Angeles, where African Americans were subjected to police brutality and surveillance reminiscent of apartheid times in South Africa. While some graffiti is undeniably destructive, other street artists, calling themselves “writers,” use their spray cans to express pride in their neighborhoods and their ethnic and racial heritages. They also call attention to various inequities and injustices. As Jim Prigoff and other commentators have noted, these expressions are also serious visual commentaries about life and public affairs.

Following the historic Watts Rebellion of 1965, iconic African American artists including Noah Purifoy, John Outterbridge, Betye Saar, Joe Sims, Charles Dickson, Dominique Moody and many others revolutionized American art history by turning “trash into treasure,” creating a new genre of assemblage art in the process. Their works collectively used found materials to offer trenchant commentary about racial and class inequities in Los Angeles and throughout America. More recently, Shepard Fairey and Robbie Conal have gained international fame as poster artists known for their “unlawful” works. Fairey, whose “OBEY” and “HOPE” (for the first Obama campaign) has garnered continued attention for his posters and murals. Likewise, Conal has been at the forefront of “guerrilla” art; his iconic posters lambasting the reactionary Supreme Court members, among many other right-wing targets, have kept him in the public limelight.

As with these predecessors, Powers has no formal permit from city authorities; she simply stakes out her sites, sets up her ladder and attaches the prefabricated work. The result is especially evocative of the folk art of Simon Rodia, creator of the internationally famous Watts Towers. That is also a powerful and enduring tradition, which is alive in multiple places in Los Angeles, the United States and throughout the entire world.

Powers collects the ingredients of her art — chairs, rugs, magnets — from discarded or donated materials, and assembles them into an intriguing whole in her backyard studio on a quiet residential street only a few blocks from my own.

Powers came to art later in life, approximately six years ago, approximately at the start of the latest wave of gentrification. But this was not her motivation; she simply sought an outlet for her creative impulses. If anything, the wave of horrific American school shootings provided one motivation for her turn to art. After 30 years of working in software development, she moved to the Los Angeles area from New England, where she had raised two children as a single mother. As she experimented with welding and fabricating materials foraged from the alleys and other locales in Mar Vista, she discovered her passion for public street art. These works have been appearing in the past few years and have intensified during the pandemic.

Powers collects the ingredients of her art — chairs, rugs, magnets — from discarded or donated materials, and assembles them into an intriguing whole in her backyard studio on a quiet residential street only a few blocks from my own. Her studio is itself a massive artwork, similar to her front lawn, which is full of sculptural pieces from similar found materials she has scrounged or discovered. These works are highly colorful and immediately catch the attention of passersby. When Powers completes a sculpture, she proceeds to the telephone pole she has selected. At first, she worked late at night to avoid public exposure, sometimes donning a fake beard to conceal her identity. Eventually, she abandoned this ruse and began erecting her public artworks during the day, in full sight of all passersby. The mounting process is meticulous. Sometimes she uses an assistant, but in all cases the artworks are securely attached to ensure that they will not fall and injure anyone. No instances of any failures in this area have been reported to date.

Only a few examples of opposition to her efforts have occurred since she commenced her public art project. She showed me, for example, a fairly long letter from a resident who threatened to alert the city authorities and demanded that her works be removed from the neighborhood telephone poles. The writer complained about safety issues, but the tone suggested a deeper, more inexplicable hostility. I found the letter a sad but extremely unusual response; fortunately, even if the writer actually followed through with the threats, no formal municipal action has been forthcoming. I witnessed a second act of hostility while jogging through the neighborhood, when a car with a young woman driver complained that she objected to the work and demanded that it be taken down from the pole.

For all of my long career writing about art and visual culture, my focus has been on works that specifically address social and political misconduct and injustice like racism, sexism, homophobia, war, poverty, class oppression and similar themes. Powers’ works are different yet share a life-affirming commitment to bring joy to viewers and encourage them to seek creativity within themselves. There is plenty of room for that feature of visual art in addition to trenchant social criticism. The human condition is complex and people need hope for their spirits to maintain the healthy indignation at the root of all social activism. Powers’ Mar Vista public sculptures cannot stop the advance of gentrification or the real estate bonanza enriching the most affluent population of Los Angeles. But they are a welcome sign of joyful resistance, or perhaps at least a few moments of quiet reflection among some viewers, one small step in that direction.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.