Where Black Lives Don’t Matter: Serial Murder and Silence in South L.A.

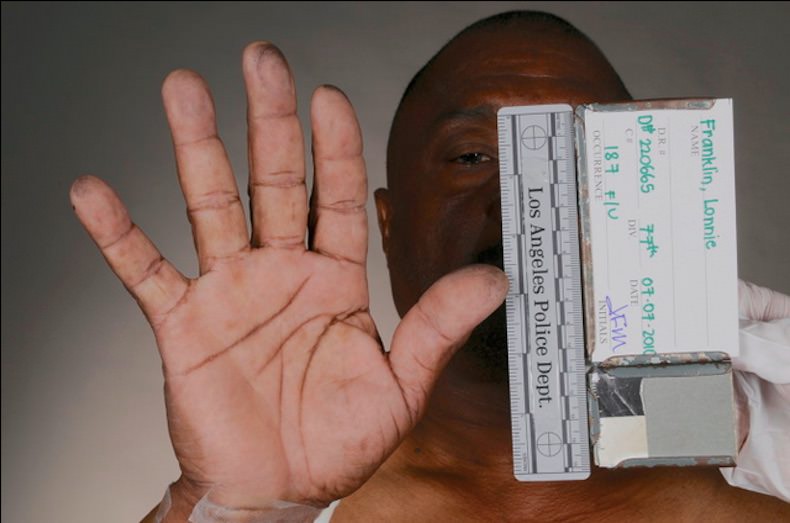

Police don’t always to have to shoot to kill black people "Tales of the Grim Sleeper," which debuts Monday on HBO, shows how the devaluing of black women’s lives allowed a serial killer to roam free for 25 years Police don’t always to have to shoot to kill black people. Lonnie Franklin Jr., shown in this movie still from NickBroomfield.com, is accused of being the Grim Sleeper serial killer.

Lonnie Franklin Jr., shown in this movie still from NickBroomfield.com, is accused of being the Grim Sleeper serial killer.

By Meleiza Figueroa and Alan Minsky

In “Tales of the Grim Sleeper,” Nick Broomfield‘s harrowing new documentary, we learn a sad and startling fact: that Los Angeles police officers once regularly used the term “NHI” — for “no human involved” — to describe the murders of prostitutes and drug addicts in poor black communities.

The film, which chronicles the long and tragic saga of the Grim Sleeper serial killer’s 25-year reign of terror in a South Los Angeles neighborhood, is a damning testament to the widespread, almost casual eradication of black lives by law enforcement — in its word and deeds.

Right now, the United States is grappling with the issue of police violence against black people, as protesters around the country declare that “black lives matter.” Broomfield’s film focuses on a parallel pathology: that “black-on-black” crime is not only tolerated but is implicitly sanctioned by the state, as illustrated by events shown in the documentary. To fully grasp the sense of alienation and hostility that black communities have toward the police, this aspect has to be understood. Millions of black people intimately understand that police departments in the U.S. are not there to protect them or their communities. That their lived experiences are continually denounced and ignored by law enforcement, government officials, the media and many of their fellow citizens speaks to how deep this pathological denial runs through American society.

Perhaps this is no mere oversight. At the core of the modern liberal state, the bedrock of American “democracy,” is the assumed equality of the nation’s citizens: “All men are created equal.” While the civil rights movement has struggled, and in several ways prevailed, against inequality for black Americans in the political sphere, it has been a much more monumental challenge to show how these inequalities operate on the level of everyday life in black communities. For all the media coverage of police violence in Ferguson, North Charleston, New York City, and elsewhere, most people who reside outside of impoverished black communities have no sense of what it’s like to live in a place where the law disregards, and is even hostile to, the needs of its residents. As such, “Tales of the Grim Sleeper” is an essential film for this historical moment, as it shows powerfully how the facts on the ground resolutely expose the lie of “liberty and justice for all.” It does this by showing a driver’s side view of the “other America” that black people experience.

The film begins with the 2010 arrest of Lonnie Franklin, a South Los Angeles resident whose DNA was linked to multiple Grim Sleeper murders going back to 1985. He is currently awaiting trial for 10 counts of murder and one count of attempted murder, and at least 10 additional murder cases are pending against him. While the actual count of his alleged victims is unknown, police found photos of at least 180 women in his home, and some fear that the final number could reach well over 100.

Most of the victims were black women who were criminalized as addicts and walked the streets as prostitutes, victims also of the crack epidemic that swept through black communities in L.A. beginning in the 1980s.

Franklin was a well-known and relatively respected fixture in his neighborhood, and Broomfield sets out to understand not only Franklin’s life, circumstances and possible motives, but also the grave errors and inconsistencies in the LAPD’s investigation of the Grim Sleeper murders that allowed a prolific serial killer to go free for over two decades. Even when the LAPD had recognized that a serial killer was targeting women in Franklin’s neighborhood (by the time the third victim was found), the community was not informed of the potential danger lurking in their midst. Crucial pieces of information — such as eyewitness reports, police sketches, a recording of a 911 call presumed to have been made by the killer and a description of Franklin’s vehicle (a very distinctive orange Pinto) — were withheld from the public for more than 20 years.

Several of the film’s interviewees — including members of the Black Coalition Fighting Back Serial Murders, an organization that formed to demand accountability from law enforcement and city officials and to inform the community about the Grim Sleeper when residents realized that a killer was in their midst — questioned how and why the LAPD could have exhibited such shocking negligence in the face of the mounting deaths. As the film progresses, it becomes distressingly clear that the victims’ social status as poor black women was a key factor in how they, and their community, were treated by the LAPD. As Nana Gyamfi, an attorney and coalition member featured in the film, pointed out: “Imagine if they had treated Victim No. 3 as if she were a student at UCLA, with blonde hair and blue eyes. How many other people might still be living? That is for me the real tragedy … the lack of concern allowed so many more people to be murdered.”

The social circumstances under which these black women’s lives, and the safety of their community, were so utterly disregarded by law enforcement speaks powerfully to the “perfect storm” of race, gender and class that lies at the heart of this story. Even though police did not have a direct hand in their murders, the silent deaths of these black women must be included in the national conversation about police brutality and racism in this post-Ferguson moment. It is especially important given that the deaths that gave rise to the “Black Lives Matter” movement were largely the result of police killings of young black men like Eric Garner and Michael Brown. Far less attention has been paid to the black women and girls who have also been victims of police violence, including Rekia Boyd, Aiyana Jones, Sheneque Proctor (portrayed in the media as “the female Eric Garner”) and far too many others.Radical activists and academics use the term “intersectionality” to describe how multiple articulations of social status — such as race, gender and class — shape how particular oppressions operate for certain groups of people. While the racism endemic to a white supremacist society and system of law enforcement casts black men as dangerous “thugs” and “demons,” the sexism that is also intrinsic to such a system works to render black women practically invisible. While misogyny provided the impetus for Franklin’s alleged crimes, the victims’ social invisibility as poor black women ignored and criminalized by the system allowed the atrocities to continue unimpeded.

Poverty and homelessness also emerge as defining characteristics of a world in which the Grim Sleeper’s victims died out of sight and out of mind of the justice system that was supposed to protect them. As Broomfield tells his audience: “This is not just a story about Lonnie, but about a people in one of the world’s most prosperous cities that have been left behind.” Indeed, like many poor black districts in the nation’s major urban centers, the racial dynamics of South L.A., and the community’s relationship to the police, cannot be understood outside the context of the titanic political and economic shifts of the past 40 years. In that time, the structural changes that have affected the U.S. economy as a whole have also changed the roles that black lives and black labor have played in American society.

Ironically, black lives mattered (to a point) in the days of chattel slavery, insofar as enslaved black people were the “valuable” property of masters and provided the free agricultural labor on which the development of the American economy depended. In the 20th century, and especially during and after World War II, black folks flocked to the nation’s cities to fill the need for jobs in the industrial and public sectors. It can be argued that their essential contributions to the postwar economy encouraged them as they organized and fought for desegregation and the right for political participation during the civil rights movement’s peak years.

Since the 1970s, however, these high-quality living-wage jobs have largely evaporated as industries fled the U.S. and the public sector began to be eroded by budget cuts and privatization. Nearly a third of black youths aged 20 to 25 in the U.S. are now unemployed; for black teens, the rate climbs to nearly half, or 49 percent (about twice the average for white youths of similar age). On top of that, the massive influx of crack into U.S. cities beginning in the 1980s, the criminalization of poverty, the rise of mass incarceration and the school-to-prison pipeline, and the subprime housing crisis have disproportionately impacted communities of color, and black communities in particular. These economic and social dynamics, writ large, have produced a mass of unemployed “surplus” labor that remains in the decaying urban cores of the nation’s major metropolitan areas, surviving by whatever means are available to them (for example, by dealing stolen cars, as Franklin did, or through prostitution, like many of his alleged victims).

In these hard economic times, black communities find themselves in a situation in which a neoliberal state and its institutions would prefer to wash their hands of any responsibility to the descendants of those who were enslaved to build this country. As an effectively “disposable” population, poor and working-class black people went from being perceived as a “necessary evil” to being seen as an intractable problem, a thorn in the side of America’s triumphant self-image; a population to be contained and disappeared rather than citizens that deserve to be protected and served. In this context, mass incarceration, state neglect and police violence work in concert to rob millions of black lives of basic dignity, protection and even the right to exist.

Although Franklin has yet to stand trial for the victims’ deaths, the film portrays him as the Grim Sleeper from its opening scenes. However, it becomes clear that there are other mysteries surrounding these murders that are far from solved. From beginning to end, questions remain: How could all of greater Los Angeles, and the impacted communities themselves, be largely unaware that a serial killer was murdering young women over more than two decades? (The assumption is that if the communities had been alerted, many of those women would still be alive.) And how could the law enforcement and media apparatuses not be concerned with performing their basic civic duties?

In subtle ways, and at a few key moments, a shocking possibility is insinuated: that Lonnie Franklin, the accused serial killer, had allies within law enforcement that allowed him to remain free, even though he was arrested and convicted well over a dozen times for other crimes, including several felonies. We are left with a vague sense that Franklin had some kind of relationship with the LAPD that enabled him to quietly “clean up the streets” for two decades — a sense that the film does not confirm, as Franklin still awaits trial four years after having been arrested (a fact which adds to the uncanny mystery). By the end of the film, this central dimension of the story remains unresolved but leaves the viewer with a haunting distrust of law enforcement — analogous to the inescapable anxiety experienced every day by members of the black community.The film also leaves us with a broader social mystery: of how, in what is arguably the cultural and communications capital of the world, a community can experience such violence and remain so invisible. Generally, serial killers are hot copy for media outlets, but when their victims are among those considered the detritus of society, even the sensational nature of the crimes cannot shed light on the grave threats faced by poor black women in these communities. The film’s exposure of the LAPD’s egregious negligence in the Grim Sleeper case easily casts them as co-villains in these crimes. But it also begs the question of how we may all be complicit, when the term “crack whore” has become a common cultural signifier for someone undeserving of basic regard or respect, whose life and humanity can simply be written off.

Perhaps Broomfield’s greatest success is his commitment to recognizing the humanity of the film’s invisible subjects, and placing this humanity at the forefront of the central narrative. For much of the film, we ride with Broomfield and his main interlocutor, Pam, a recovering crack addict and Franklin’s former girlfriend, as they drive the streets of Los Angeles to track down key associates, witnesses and surviving victims — many of whom were homeless, sex workers or crack addicts, and many of whom police investigators never attempted to contact. That the filmmakers did a better investigative job over the course of several months than an LAPD task force assigned to the murders did in 25 years speaks volumes about the intractable challenge of seeking and securing justice for a community that law enforcement never had any intention of providing.

As the film proceeds, we increasingly see through Pam’s eyes; and through the film’s evocative interviews and encounters with Franklin’s friends, family members, acquaintances and alleged victims, we come to care for this invisible community. Thus, we fully grasp the cruelty of a society that refuses to acknowledge that their lives matter. But Margaret Prescod — founder of the Black Coalition Fighting Back Against Serial Murders — notes that the story of these crimes must also be viewed “in the context … of a community that has survived against all odds.”

“Tales of the Grim Sleeper” succeeds — where other progressive media stories often do not — in showing us that even in the face of the incredible injustices inflicted on black women in this community, this is not simply a story of their victimization, but also of their struggle to be recognized as human beings and citizens. It is telling that decades before “Black Lives Matter,” the main slogan of the Black Coalition Fighting Back Serial Murders was “Every Life is of Value: Black Women’s Lives Count.” And as one of the Grim Sleeper’s survivors insisted in the film, with tearful and indignant affirmation: “Yes, I was out there [on the streets]. But that doesn’t mean I’m nothing. It doesn’t mean I’m nothing.”

In a political moment when millions of people in the United States are inspired to address the deep-seated racism that corrupts our judicial system, “Tales of the Grim Sleeper” is a stunning testimony to a reality experienced by so many people but denied by the dominant society and its institutions — and to just how much needs to be rectified for every person in this country to be valued equally.

“Tales of the Grim Sleeper” debuts Monday, April 27, on HBO.

Meleiza Figueroa is a doctoral candidate in geography at the University of California, Berkeley, and an Oakland-based activist. Alan Minsky is the program director of KPFK Radio in Los Angeles.

Your support matters…Independent journalism is under threat and overshadowed by heavily funded mainstream media.

You can help level the playing field. Become a member.

Your tax-deductible contribution keeps us digging beneath the headlines to give you thought-provoking, investigative reporting and analysis that unearths what's really happening- without compromise.

Give today to support our courageous, independent journalists.

You need to be a supporter to comment.

There are currently no responses to this article.

Be the first to respond.